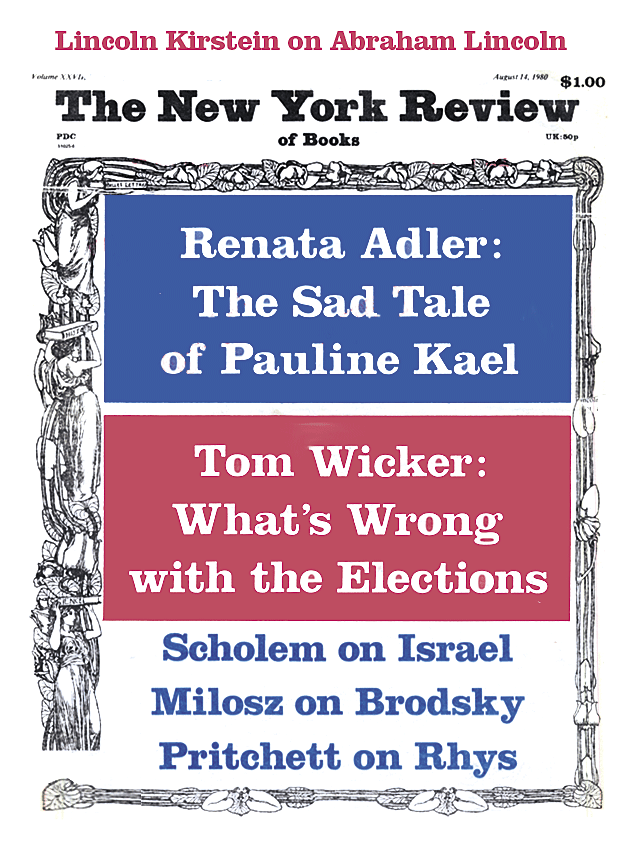

Now, When the Lights Go Down, a collection of her reviews over the past five years, is out; and it is, to my surprise and without Kael- or Simon-like exaggeration, not simply, jarringly, piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption, worthless. It turns out to embody something appalling and widespread in the culture. Over the years, that is, Ms. Kael’s quirks, mannerisms, tactics, and excesses have not only taken over her work so thoroughly that hardly anything else, nothing certainly of intelligence or sensibility, remains; they have also proved contagious, so that the content and level of critical discussion, of movies but also of other forms, have been altered astonishingly for the worse. To the spectacle of the staff critic as celebrity in frenzy, about to “do” something “to” a text, Ms. Kael has added an entirely new style of ad hominem brutality and intimidation; the substance of her work has become little more than an attempt, with an odd variant of flak advertising copy, to coerce, actually to force numb acquiescence, in the laying down of a remarkably trivial and authoritarian party line.

She has, in principle, four things she likes: frissons of horror; physical violence depicted in explicit detail; sex scenes, so long as they have an ingredient of cruelty and involve partners who know each other either casually or under perverse circumstances; and fantasies of invasion by, or subjugation of or by, apes, pods, teens, bodysnatchers, and extraterrestrials. Whether or not one shares these predilections—and whether they are in fact more than four, or only one—they do not really lend themselves to critical discussion. It turns out, however, that Ms. Kael does think of them as critical positions, and regards it as an act of courage, of moral courage, to subscribe to them. The reason one cannot simply dismiss them as de gustibus, or even as harmless aberration, is that they have become inseparable from the repertory of devices of which Ms. Kael’s writing now, almost wall to wall, consists.

She has an underlying vocabulary of about nine favorite words, which occur several hundred times, and often several times per page, in this book of nearly six hundred pages: “whore” (and its derivatives “whorey,” “whorish,” “whoriness”), applied in many contexts, but almost never to actual prostitution; “myth,” “emblem” (also “mythic,” “emblematic”), used with apparent intellectual intent, but without ascertainable meaning; “pop,” “comicstrip,” “trash” (“trashy”), “pulp” (“pulpy”), all used judgmentally (usually approvingly) but otherwise apparently interchangeable with “mythic”; “urban poetic,” meaning marginally more violent than “pulpy”; “soft” (pejorative); “tension,” meaning, apparently, any desirable state; “rhythm,” used often as a verb, but meaning harmony or speed; “visceral”; and “level.” These words may be used in any variant, or in alternation, or strung together in sequence—“visceral poetry of pulp,” e.g., or “mythic comic-strip level”—until they become a kind of incantation. She also likes words ending in “ized” (“vegetabilized,” “robotized,” “aestheticized,” “utilized,” “mythicized”), and a kind of slang (“twerpy,” “dopey,” “dumb,” “grungy,” “horny,” “stinky,” “drip,” “stupes,” “crud”) which amounts, in prose, to an affectation of straightforwardness.

I leave aside for the moment Ms. Kael’s incessant but special use of words many critics use a lot: “we,” “you,” “they,” “some people”; “needs,” “feel,” “know,” “ought”—as well as her two most characteristic grammatical constructions: “so/that” or “such/that,” used not as a mode of explication or comparison (as in, e.g., he was so lonely that he wept), but as an entirely new hype connective between two unrelated or unformulated thoughts; and her unprecedented use, many times per page and to new purposes, of the mock rhetorical question and the question mark.

Because what is most striking is that she has, over the years, lost any notion of the legitimate borders of polemic. Mistaking lack of civility for vitality, she now substitutes for argument a protracted, obsessional invective—what amounts to a staff cinema critics’ branch of est. Her favorite, most characteristic device of this kind is the ad personam physical (she might say, visceral) image: images, that is, of sexual conduct, deviance, impotence, masturbation; also of indigestion, elimination, excrement. I do not mean to imply that these images are frequent, or that one has to look for them. They are relentless, inexorable. “Swallowing this movie,” one finds on page 147, “is an unnatural act.” On page 151, “his way of pissing on us.” On page 153, “a little gas from undigested Antonioni.” On page 158, “these constipated flourishes.” On page 182, “as forlornly romantic as Cyrano’s plume dipped in horse manure.” On page 226, “the same brand of sanctifying horse manure.” On page 467, “a new brand of pop manure.” On page 120, “flatulent seriousness.” On page 226, “flatulent Biblical-folk John Ford film.” On page 353, “gaseous naïveté.” And elsewhere, everywhere, “flatulent,” “gaseous,” “gasbag,” “makes you feel a little queasy,” “makes you gag a little,” “just a belch from the Nixon era,” “you can’t cut through the crap in her,” “plastic turds.” Of an actress, “She’s making love to herself”; of a screenwriter, “He’s turned in on himself; he’s diddling his own talent.” “It’s tumescent filmmaking.” “Drama and politics don’t climax together.” Sometimes, one has the illusion that these oral, anal, or just physical epithets have some meaning—“Taxi Driver is a movie in heat,” for instance, or “the film is an icebag.” But then: “Coma is like a prophylactic.” One thinks, How, how is it like a prophylactic? “It’s so cleanly made.” Or a metaphor with a sadistic note which defies, precisely, physical comprehension. “The movie has had a spinal tap.”