In the New Yorker, James Wood explores the eccentric sense of playfulness in W. G. Sebald’s writing.

I met W. G. Sebald almost twenty years ago, in New York City, when I interviewed him onstage for the PEN American Center. Afterward, we had dinner. It was July, 1997; he was fifty-three. The brief blaze of his international celebrity had been lit a year before, by the publication in English of his mysterious, wayward book “The Emigrants.” In a review, Susan Sontag (who curated the penseries) had forcefully anointed the German writer as a contemporary master.

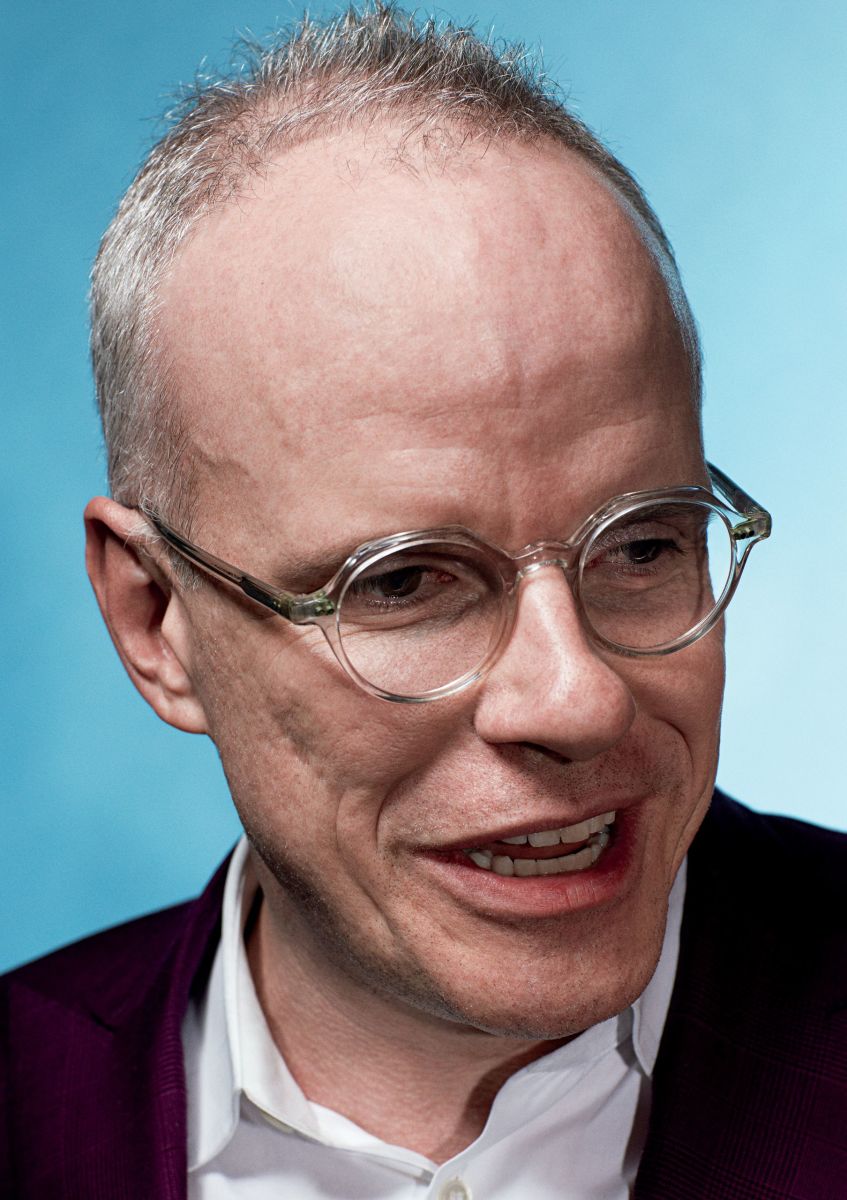

Not that Sebald seemed to care about that. He was gentle, academic, intensely tactful. His hair was gray, his almost white mustache like frozen water. He resembled photographs of a pensive Walter Benjamin. There was an atmosphere of drifting melancholy about him that, as in his prose, he made almost comic by sly self-consciousness. I remember standing with him in the foyer of the restaurant, where there was some kind of ornamental arrangement that involved leaves floating in a tank. Sebald thought they were elm leaves, which prompted a characteristic reverie. In England, he said, the elms had all but disappeared, ravaged first by Dutch elm disease, and then by the great storm of 1987. All gone, all gone, he murmured. Since I had not read “The Rings of Saturn” (published in German in 1995 but not translated into English until 1998), I didn’t know that he was almost quoting a passage from his own work, where, beautifully, he describes the trees, uprooted after the hurricane, lying on the ground “as if in a swoon.” Still, I was amused even then by how very Sebaldian he sounded, encouraged thus by a glitter in his eyes, and by a slightly sardonic fatigue in his voice.

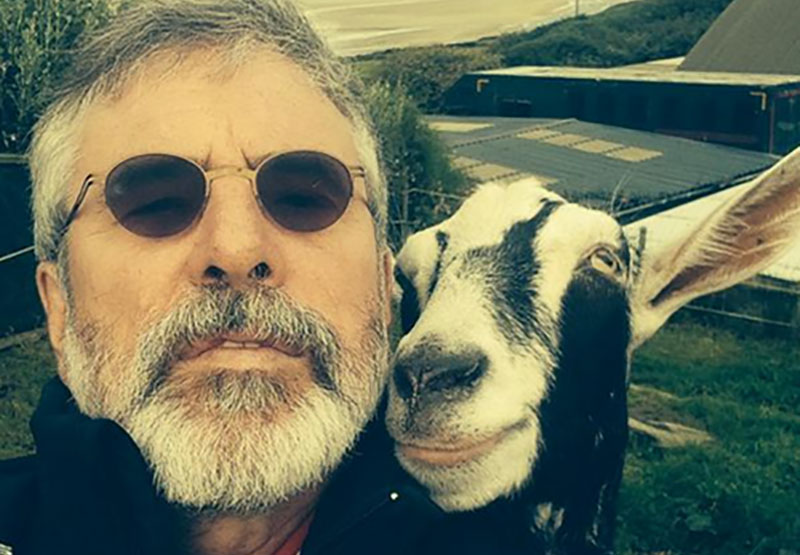

During dinner, he returned sometimes to that mode, always with a delicate sense of comic timing. Someone at the table asked him if, given the enormous success of his writing, he might be interested in leaving England for a while and working elsewhere. (Sebald taught for more than thirty years, until his death, in 2001, in Norwich, at the University of East Anglia.) Why not New York, for instance? The metropolis was at his feet. How about an easy and well-paid semester at Columbia? It was part question, part flattery. Through round spectacles, Sebald pityingly regarded his interlocutor, and replied with naïve sincerity: “No, I don’t think so.” He added that he was too attached to the old Norfolk rectory he and his family had lived in for years. I asked him what else he liked about England. The English sense of humor, he said. Had I ever seen, he asked, any German comedy shows on television? I had not, and I wondered aloud what they were like. “They are simply . . . indescribable,” he said, stretching out the adjective with a heavy Germanic emphasis, and leaving behind an implication, also comic, that his short reply sufficed as a perfectly comprehensive explanation of the relative merits of English and German humor.

Comedy is hardly the first thing one associates with Sebald’s work, partly because his reputation was quickly associated with the literature of the Holocaust, and is still shaped by the two books of his that deal directly with that catastrophe: “The Emigrants,” a collection of four semi-fictional, history-haunted biographies; and his last book, “Austerlitz” (2001), a novel about a Jewish Welshman who discovers, fairly late in life, that he was born in Prague but had avoided imminent extermination by being sent, at the age of four, to England, in the summer of 1939, on the so-called Kindertransport. The typical Sebaldian character is estranged and isolate, visited by depression and menaced by lunacy, wounded into storytelling by historical trauma. But two other works, “Vertigo” (published in German in 1990 and in English in 1999) and “The Rings of Saturn,” are more various than this, and all of his four major books have an eccentric sense of playfulness.

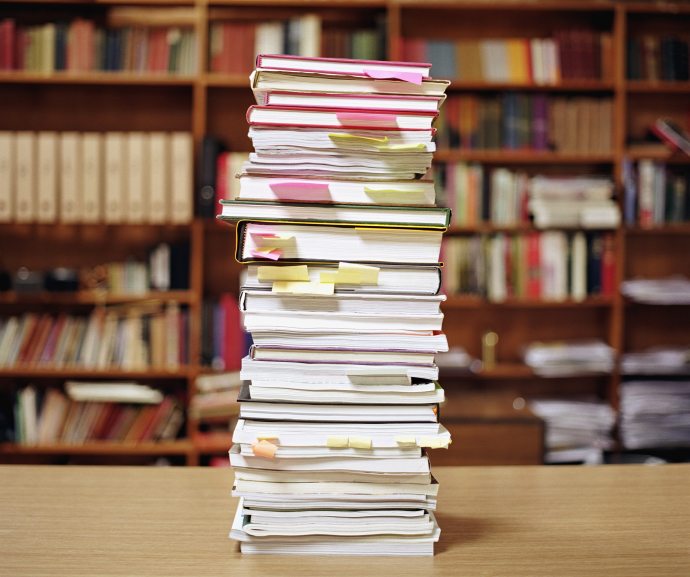

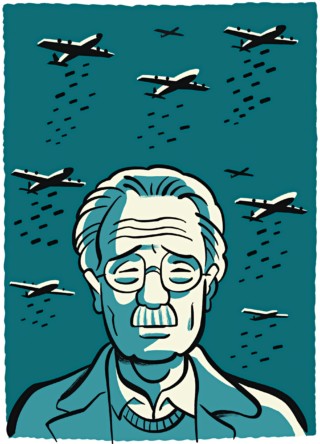

Rereading him, in handsome new editions of “Vertigo,” “The Emigrants,” and “The Rings of Saturn” (New Directions), I’m struck by how much funnier his work is than I first took it to be. Consider “The Rings of Saturn” (brilliantly translated by Michael Hulse), in which the Sebald-like narrator spends much of the book tramping around the English county of Suffolk. He muses on the demise of the old country estates, whose hierarchical grandeur never recovered from the societal shifts brought about by the two World Wars. He tells stories from the lives of Joseph Conrad, the translator Edward FitzGerald, and the radical diplomat Roger Casement. He visits a friend, the poet Michael Hamburger, who left Berlin for Britain in 1933, at the age of nine. The tone is elegiac, muffled, and yet curiously intense. The Hamburger visit allows Sebald to take the reader back to the Berlin of the poet’s childhood, a scene he meticulously re-creates with the help of Hamburger’s own memoirs. But he also jokily notes that when they have tea the teapot emits “the occasional puff of steam as from a toy engine.”

(…)