I’m Very Into You is a collection that includes 103 pages of emails that Acker and Ken Wark exchanged over seventeen days at the dawn of the internet era. Acker met Wark in Sydney during the summer of 1995, and the two had a brief but intense affair before she returned home to San Francisco. Wark, now a professor at the New School for Social Research and a renowned media theorist, was thirty-four when he met Acker (she was forty-eight). At the time, Wark was part of a Melbourne-based post-Marxist anarchist group that produced the political and cultural journal Arena. He had just published his first book, Virtual Geography, about the emergence of global media space and the transmission of world events as media spectacles. He was enjoying a precocious career as a national media commentator in Australia and advising government ministers on media access, while still living a kind of post-student life among artists and activists. He had boyfriends and girlfriends, often concurrently, and wondered about his identity, queerness and straightness, performance, butch/femme-ness, masculinity. Of course he’d read Acker. He’d been following her work since the ’80s.

The search for connection through sex is at the forefront of all of Acker’s writing. She was single for most of her life (and writing always from within her life, and around and beyond it). As passages from her novels show, on-tour flirtations and hookups and romances weren’t uncommon. While touring in the summer of 1995, something more compelling than a mere fling developed between her and Wark. His first email begins as a gracious note sent to a casual lover. He’d driven to work the next day in a daze; he’d enjoyed spending time with her and was starting to read the William S. Burroughs novel she’d talked about. But as he continues, he opens the door to something more complicated: “There are no words,” he writes. “I just want to say there are no words.… Bear with me. I’ll have something to say for myself sometime soon. When I remember who I thought I was in the first place. Even if I’ve been displaced a little from wherever that was.” She responds, delighted: through the exhaustion and jet lag of travel, “your message is changing the day… all the time there (in Sydney) that I didn’t know what was going on… what becomes/became present was how easy it is to be with you. Like: you are the one I want/wanted to talk to.”

In London, at the height of her fame, Acker had been involved in an increasingly maddening long-distance BDSM romance with a married journalist referred to as “the German” and “the reporter” in her 1990 novel, In Memoriam to Identity. “Being with him made me remember that I’ve always looked for my childhood,” she’d write to Wark. Still, his control of her, which began as sexual play, became increasingly total as he suspended contact for weeks and cut short their meetings. What began as a fulfilling and sexy relationship between her “bratty sub” and his “strict Dominant” evolved into a draining, old-fashioned affair between a distant and married straight man and his long-suffering mistress. As she’d write at the height of her correspondence with Wark, fearing their friendship might take a turn in that direction: “So. Regarding het shit. These games. To me, top/bottom is just stuff that happens in bed. Who fistfucks whom. Outside the bed, I do my work and you do yours. I fucking hate power games outside the bed and have no interest in playing them.”

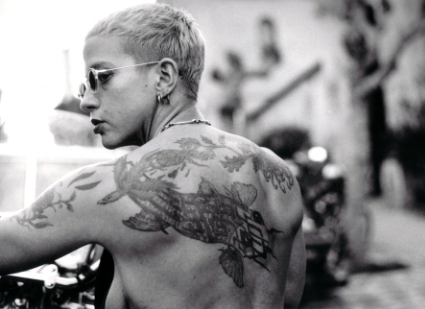

Chris Kraus on Kathy Acker

In The Believer