Featured in Granta Magazine, Nuar Alsadir’s essay ‘Clown School’ examines selfhood and performance:

After my first day of clown school I tried to drop out. The instructor was provoking us in a way that made me uncomfortable – to the nervous smiley woman, ‘Don’t lead with your teeth;’ to the young hipster, ‘Go back to the meth clinic,’ and to me, ‘I don’t want to hear your witty repartee about Oscar Wilde.’

I was the only non-actor in the program and had made the mistake, as we went around the circle on the first day, of telling everyone that I was a psychoanalyst writing a book about laughter. As part of my research, I explained, I’d frequented comedy clubs and noticed how each performance, had it been delivered in a different tone of voice and context, could have been the text of a therapy session. Audience members, I told them, laughed less because a performer was funny than because they were honest. Of course that’s not how all laughter operates, but the kind of laughter I’m interested in (spontaneous outbursts) seems to function that way, and clown pushes that dynamic to its extreme – which is why I decided to enroll in clown school, and how I earned the grating nickname ‘smarty pants’.

But if I dropped out, I’d lose my tuition money. So I decided to stay, and, by staying, was provoked, unsettled, changed.

*

There’s a knee-jerk tendency to perceive provocation as negative – like how in writing workshops participants often call for the most striking part of a work to be cut. When we are struck, there’s a brief pause during which the internal dust is kicked up – we lose our habitual bearings, and an opening is created for something unexpected to slip in. Habit protects us from anything we don’t have a set way of handling. As it’s when we’re off-guard that we’re least automatous, it’s then that we’re most likely to come up with spontaneous, uncurated responses.

It turned out the perpetually-smiling woman was sad, the hipster (who didn’t even do drugs) acted high as a way of muting the parts of his personality he was afraid we would judge, and I found it easier to hide behind my intellect than expose myself as a flawed and flailing human being. Each role, in other words, offered a form of protection: by giving off recognizable signals to indicate a character type, we accessed a kind of invisibility. We cued people to look through us to the prototypes we were referencing. When the instructor satirized those roles, he defamiliarized them so that the habitual suddenly became visible. His provocations knocked the lids off the prototypes we were hiding inside of, in a similar way to how many psychoanalysts, in the attempt to understand a person’s conflicts, begin by analyzing their defenses – what is being used as cover – before moving on to what is being covered up and why.

Both psychoanalysis and the art of clowning – though in radically different ways – create a path towards the unconscious, making it easier to access the unsocialized self, or, in Nietzsche’s terms, to ‘become the one you are.’ Psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott considered play ‘the gateway to the unconscious’, which he divided into two parts: the repressed unconscious that is to remain hidden and the rest of the unconscious that ‘each individual wants to get to know’ by way of ‘play’, which, ‘like dreams, serves the function of self-revelation’. In clown school, the part of the mind that psychoanalysis tries to reveal – by analyzing material brought into session, including dreams or play – is referred to as a person’s clown.

*

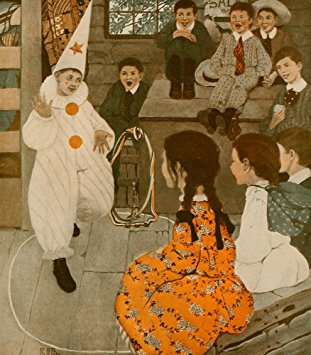

Each of us has a clown inside of us, according to Christopher Bayes, head of physical acting at the Yale School of Drama and founder of The Funny School of Good Acting, where I was taking my two-week, six-hours-per-day workshop. The theatrical art of clowning – commonly referred to as ‘clown’ – is radically different from the familiar images of birthday party, circus or scary clowns. Bayes’ program helps actors find their inner clown. The self-revelation that results provides access to a wellspring of playful impulses that they can then tap into during creative processes. His method stems from the French tradition developed by his former teachers Jacques Lecoq and Phillippe Gaulier – the kind of training the fictional main character of Louis CK and Zach Galifankis’ TV series Baskets seeks, and that Sascha Baron Cohen, Emma Thompson and Roberto Begnini underwent early in their careers.

Lecoq, who began as a physiotherapist, believed ‘the body knows things about which the mind is ignorant’ – a phrase that could be applied to the unconscious. The process of trying to find your clown involves going through a series of exercises that strip away layers of socialization to reveal the clown that had been there all along – or in Winnicott’s terms, your ‘true self’.

*

(…)