(…)

Baba Seva—Seva Efraimovna Gekhtman—was born in a small town in Ukraine in 1919. Her father was an accountant at a textile factory and her mother was a nurse. Her parents moved to Moscow with her and her brothers when she was a child. I knew that she had excelled in school and had been admitted to Moscow State University, the best and oldest university in Russia, where she studied history. I knew that at Moscow State, not long after the German invasion, she had met a young law student, my grandfather, and that they had fallen in love and married. Then he was killed near Vyazma in the second year of the war, just a month after my mother was born. I knew that after the war my grandmother had started lecturing at Moscow State, and had consulted on a film about Ivan the Great (“gatherer of the lands of Rus”) which so reminded Joseph Stalin of himself that he gave her an apartment in central Moscow; that despite this she was forced out of Moscow State a few years later, at the height of the “anti-cosmopolitan”—i.e., anti-Jewish—campaign; and that she got by after that as a tutor and as a translator from other Slavic languages. I knew that she had got remarried, in late middle age, to a sweet, forgetful geophysicist, whom we called Uncle Lev, and moved with him to the nuclear-research town of Dubna—vacating the Stalin apartment for my parents, and then eventually for my brother—before moving back, a couple of years before I showed up, after Uncle Lev died in his sleep.

But there was a lot I didn’t know. I didn’t know what her life had been like after the war, or whether, before the war, during the purges, she had had any knowledge, or any sense, of what was happening in the country. If not, why not? If so, how had she lived with that knowledge? I pictured myself sitting monastically in my room and setting down my grandmother’s stories in a publishable way.

The next thing I knew, I was standing in the passport-control line in the grim basement of Sheremetyevo-2 International Airport. It seemed to never change. As long as I’d been flying here, they made you come down to this basement and wait in line before you got your bags. It was like a purgatory after which you entered something other than heaven. A young, blond, unsmiling border guard took my battered blue American passport with mild disgust. He checked my name against the terrorist database and buzzed me through the gate to the other side.

I was in Russia again.

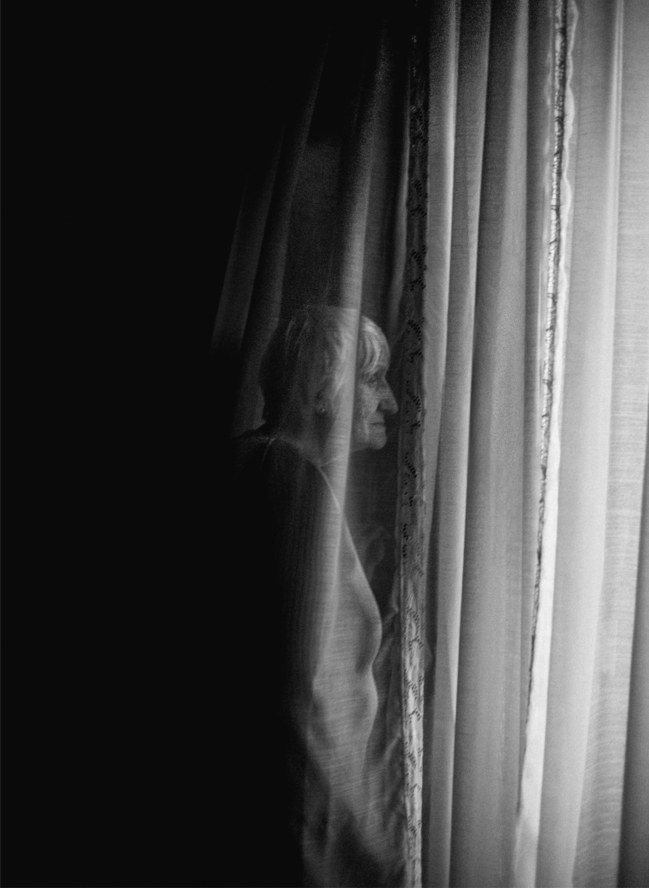

Baba Seva’s apartment was on the second floor of a white five-story building off a leafy courtyard. I entered the courtyard and tapped in the code for the front door—I still remembered it—and lugged my suitcase up the stairs. My grandmother came to the door. She was tiny. She had always been small, but now she was even smaller, and the gray hair on her head was even thinner. For a moment, I was worried she wouldn’t know who I was. But then she said, “Andryushik. You’re here.” She seemed to have mixed feelings about it.

I came in.

She wanted to feed me. Slowly and deliberately, she heated up potato soup, kotlety (Russian meatballs), and sliced fried potatoes. She moved around the kitchen at a glacial pace and was unsteady on her feet, but there were many things to hold on to in that old kitchen, and she knew exactly where they were. Her hearing had declined considerably since my last visit, so I waited while she worked and then helped her plate the food. Finally, we sat. She asked me about my life in America.

“Where do you live?”

“New York.”

“What?”

“New York.”

“Oh. Do you live in a house, or an apartment?”

“An apartment.”

“What?”

“An apartment.”

“Do you own it?”

“I rent it. With roommates.”

“What?”

“I share it. It’s like a communal apartment.”

“Are you married?”

“No.”

“No?”

“No.”

“Do you have kids?”

“No.”

“No kids?”

“No. In America,” I half-lied, “people don’t have kids until later.”

Satisfied, or partly satisfied, she then asked me how long I intended to stay.

“Until Dima comes back,” I said.

“What?” she said.

“Until Dima comes back,” I said.

She took that in.

“Andryusha,” she said. “Do you know my friend Musya?”

“Of course,” I said.

“She’s a very close friend of mine,” my grandmother explained. “And right now she’s at her dacha.” Musya, or Emma Abramovna, was my grandmother’s oldest living friend. An émigré from Poland, she had been a literature professor who had managed to hang on at Moscow State despite the anti-Jewish campaign; long since retired, she still had a dacha at Peredelkino, the old writers’ colony. My grandmother had lost her own dacha in the nineties, after Uncle Lev got swindled out of his share in a geological-exploration company he’d founded with some fellow-scientists.

“I think,” she said now, “that next summer she’s going to invite me to stay with her.”

“Yes? She said that?”

“No,” my grandmother said. “But I hope she does.”

“That sounds good,” I said. In August, most Muscovites left for their dachas; clearly, my grandmother’s inability to do the same was weighing on her mind.

(…)