Imagine the Jeff Koons retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art as the perfect storm. And at the center of the perfect storm there is a perfect vacuum. The storm is everything going on around Jeff Koons: the multimillion-dollar auction prices, the blue chip dealers, the hyperbolic claims of the critics, the adulation and the controversy and the public that quite naturally wants to know what all the fuss is about. The vacuum is the work itself, displayed on five of the six floors of the Whitney, a succession of pop culture trophies so emotionally dead that museumgoers appear a little dazed as they dutifully take out their iPhones and produce their selfies.

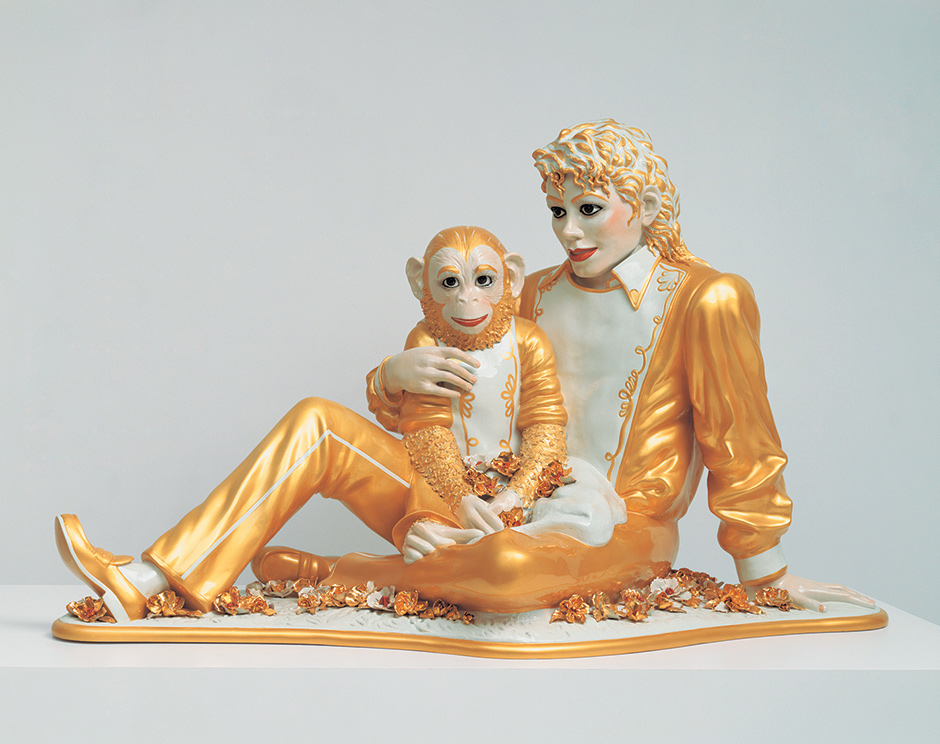

Presented against stark white walls under bright white light, Koons’s floating basketballs, Plexiglas-boxed household appliances, and elaborately produced jumbo-sized versions of sundry knickknacks, souvenirs, toys, and backyard pool paraphernalia have a chilly chic arrogance. The sculptures and paintings of this fifty-nine-year-old artist are so meticulously, mechanically polished and groomed that they rebuff any attempt to look at them, much less feel anything about them. This is the last show that the Whitney will mount in its Marcel Breuer building on Madison Avenue before moving to new quarters in the Meatpacking District, and Adam Weinberg, the museum’s director, has come up with a parting shot so swaggeringly obnoxious that it can’t be ignored.

Anybody who has taken Modern Art 101 will be able to give you some general idea of how we arrived at the point where a ten-foot-high polychromed aluminum reproduction of a multicolored pile of Play-Doh holds center stage at the Whitney—and is hailed by Roberta Smith, one of the chief art critics at The New York Times, as “a new, almost certain masterpiece.” What we are seeing at the Whitney is the mainstreaming of Dadaism and in particular of the readymade, the ordinary and frequently mass-produced objects that Marcel Duchamp reimagined as art objects, including, early on, a bicycle wheel, a bottle rack, and a urinal.

Duchamp produced his first readymades roughly a hundred years ago. At the time they were seen by hardly anybody; they were the ultimate insider’s cool dude joke art. This was a joke that Duchamp presented deadpan, with the deliberateness of a man who very carefully weighed every move he made. He had already pursued a serious career as a painter; he had created a sensation at the Armory Show in 1913 with his Nude Descending a Staircase; and he would not have abandoned painting without cause. Duchamp felt there was too much of a mystique around art. Years later, he told Calvin Tomkins, “I don’t believe in [art] with all the trimmings, the mystic trimming and the reverence trimming and so forth.” The readymade was an act of supreme skepticism; at least that is what it was for Duchamp.

The Cult of Jeff Koons

Jed Perl in the New York Review of Books