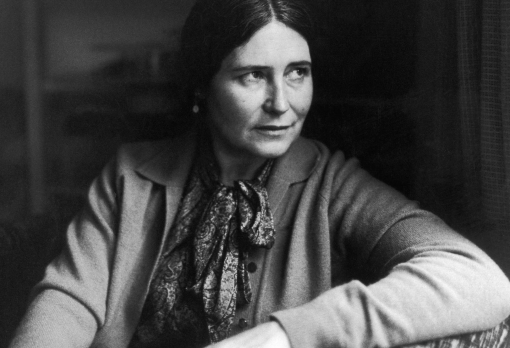

Jenny Diski on moving in with Doris Lessing as a teenager. Indispensable reading.

Over the years I called Doris ‘the woman I live with’, which I worried could be taken to have something a little unseemly or suggestive about it in those not quite yet permissive days; ‘the woman whose house I live in’ (less unseemly but odd); or most often, ‘Doris, my mumble, mumble, mumble’, ‘the person who bla bla bla’. Or I took a deep breath and went the whole hog: ‘Doris, who invited me to go and stay at her house when she heard …’ But with that the conversation was scuppered and once again, I’d end up telling the whole convoluted tale, which fairly rapidly, since Doris had also sent me to the Tavistock Adolescent Clinic to get ‘sorted out’, had become very boring, like a straightforward writing down of my life story. For a while, I decided on ‘foster mother’ but the ‘mother’ part of it made me cringe (as it certainly made Doris cringe), and a friend, who wasn’t English and didn’t know about the system of care for children, objected that it made her sound as if she had taken me in for money. So taking account of cultural understandings, another possible designation hit the dust. I occasionally tried a light-hearted ‘my benefactor’, which had a theatrical and comic edge to it, but once again required a story to be told. There was ‘my friend, Doris’ but that didn’t convey the dynamics of the relationship or the age discrepancy. ‘My fairy godmother’ was kept for those occasions when I was needing to end a conversation for my lack of interest in it. ‘Auntie Doris’ always got a laugh from Doris, and I think she suggested it as a joke when the matter came up. The name thing was an ongoing problem.

Sometimes, for lack of a solution, I thought I’d simply call her ‘my mother’, but that made me so inordinately uncomfortable, ‘mother’ and ‘my’ being more than doubly cringeworthy, that even now I feel the need to reiterate that she wasn’t really my mother. We never spoke about it in more detail than the Auntie Doris joke, but she must have had a sense of it because when my daughter was about a month old and lying on the carpet in her flat, Doris said, out of the blue, in the awkward, clipped and embarrassed tone she used for any discussion of our relationship, which I very well recognised by then: ‘Do you want her to call me grandma? Or some sort of thing like that?’ I took it for the kindly and difficult gesture it was, but awkward and embarrassed myself by her manner, I said I thought ‘Doris’ would be the best name to call her. In any case, I said, ‘she’s got two grandmothers, even if one is invisible – please god.’ I was quite taken by surprise at the thought that all along while I was trying to figure out how to refer to Doris, I actually had a real mother to call my own. But having thought that, it seemed irrelevant.