In his story ‘The Student’, Chekhov writes of a young seminarian who comes across two widows warming themselves at a fire:

And now, shrinking from the cold, he thought that just such a wind had blown … in the time of Ivan the Terrible and Peter, and in their time there had been just the same desperate poverty and hunger, the same thatched roofs with holes in them, ignorance, misery, the same desolation around, the same darkness, the same feeling of oppression – all these had existed, did exist, and would exist, and the lapse of a thousand years would make life no better.

At first this insight dismays him, but he comes to accept that the past ‘is linked with the present by an unbroken chain of events’ and that ‘he had just seen both ends of that chain; that when he touched one end the other quivered.’ He is suddenly relieved. It seems there is a permanence to things that both guarantees one’s own tribulations and makes them merely an insignificant part of a larger unalterable order. The story was written in 1894, in the aftermath of serfdom, but it expresses – however ironically – a sentiment prevailing in many of the most influential parts of black America today.

Over the past few years, roughly the entire second term of the Obama administration, a consensus has taken shape online and also in more traditional arenas of American political activism and cultural production. Inspired by the disproportionate impact of the economic collapse of 2008 and by growing awareness of the failure of the policy of mass incarceration as well as scores of high-profile travesties of justice – notably the death of Trayvon Martin and the acquittal of his murderer, George Zimmerman, which gave birth to the #BlackLivesMatter movement – alongside many more ambiguous affronts (such as the lack of nominees of colour at the 2015 Academy Awards, which gave birth to the #OscarsSoWhite campaign), the rapturous, impossibly short-lived post-raciality of the first black presidency has been usurped by a backward-looking social consciousness best expressed by the internet neologism ‘wokeness’. (Chekhov’s student ‘got woke’ that cold night in the Russian countryside.)

In times of strife, there is something seductive, even romantic, about the kind of transhistorical thinking the new social consciousness invokes, articulated most notably in Ta-Nehisi Coates’s bestseller, Between the World and Me. ‘I can’t secure the safety of my son,’ Coates said in his acceptance speech for the National Book Award. ‘I can’t go home and tell him that it’s going to be OK … I just don’t have that right, I just don’t have that power.’ The power he does have, the power anyone who is black can have, he decides, is a negative one: it lies in the refusal to buy into the possibility of progress (‘You won’t enrol me in this lie’). This sentiment, virtually unspeakable eight years ago, now permeates black cultural output, taking in everything from popular music like Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly and Beyoncé’s Lemonade, as well as her sister Solange’s A Seat at the Table, to films like Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave, Ava Duvernay’s 13th and Nate Parker’s much hyped The Birth of a Nation, to books like Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, Jesmyn Ward’s anthology The Fire This Time, James McBride’s The Good Lord Bird and the poet Claudia Rankine’s award-winning Citizen. In a recent interview with the Los Angeles Times, on receiving the MacArthur ‘Genius’ grant, Rankine acknowledged as much: ‘To me, the getting of this honour is … the culture saying: “We have an investment in dismantling white dominance in our culture. If you’re trying to do that, we’re going to help you” … The MacArthur is given to my subject through me.’ The moral of the story is clear: if you are a serious black artist working today, whether you like it or not, you’re going to have to wake up.

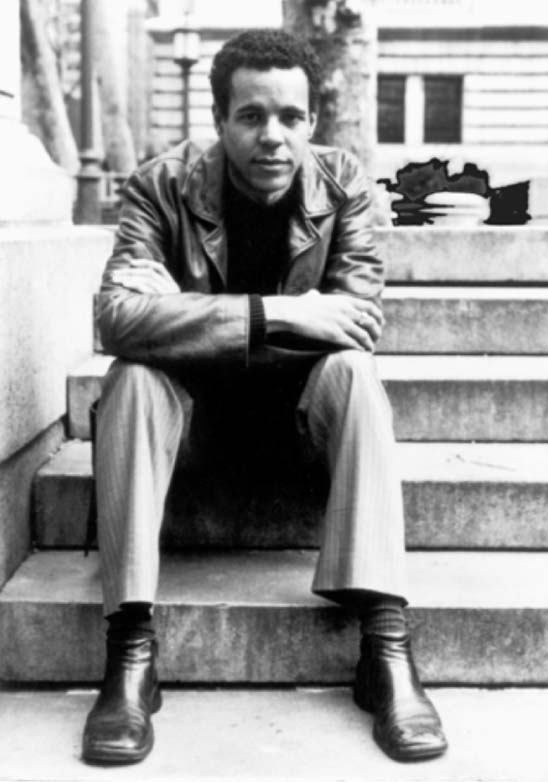

Before the publication of The Underground Railroad, his sixth novel – a mostly straightforward and historically realistic tale of a slave’s escape from southern bondage into tenuous northern freedom – it would have been difficult to imagine a less obvious candidate for the title of Woke Black Artist of the Year than the 47-year-old Colson Whitehead. He distinguished himself in his late twenties with his first novel, The Intuitionist (1999), an explosively original story set in a fantastical world of elevator inspectors, and quickly won critical acclaim on the strength of a rollicking, hyper-idiosyncratic body of work that refused to adhere to the mandates of identity politics or the constrictions of literary genre. Writing with David Foster Wallace-level verbal firepower, he was prepared to subvert the simplistic clichés attached to blackness – and the impulse towards sentimentality that goes along with them. At the height of black rapture over Obama’s election, Whitehead published an irreverent, almost flippant op-ed in the New York Times entitled ‘Finally, a Thin President’, which made a mockery of the notion that an earth-shattering symbolic power was attached to the historic achievement. The next year, he published another satirical op-ed in the New York Times, this one a guide for blocked novelists in search of fresh material. One of his more eyebrow-raising suggestions was what he called the Southern Novel of Black Misery. ‘Africans in America,’ he wrote,

cut your teeth on this literary staple. Slip on your sepia-tinted goggles and investigate the legacy of slavery that still reverberates to this day, the legacy of Reconstruction that still reverberates to this day, and crackers. Invent nutty transliterations of what you think slaves talked like. But hurry up – the hounds are a-gittin’ closer! Sample titles: ‘I’ll Love You Till the Gravy Runs Out and Then I’m Gonna Lick Out the Skillet’; ‘Sore Bunions on a Dusty Road’.

(…)

The Underground Railroad is published by Fleet (£14.99)