(…)

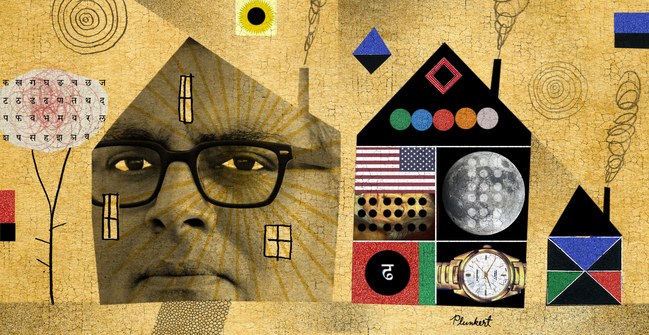

After ten or fifteen years [in the US], the confusion and loss had been replaced by a self-conscious construction of an immigrant self. I’m calling it a construction because it was an aesthetic and a textual idea. I was taking pictures of immigrant life; I was reporting on novels and nonfiction about immigrants; my own words were an edited record of what I was reading. An eclectic mix of writers: Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, June Jordan, Jamaica Kincaid, Hanif Kureishi, Salman Rushdie, Marguerite Duras, Guillermo Gómez-Peña. Reagan was still President when I came to the U.S. The Iran-Contra hearings were my introduction to televised spectacle. Gap-toothed Ollie North and his proclamations of innocence, the volume of hair on his secretary Fawn Hall, reports I read of Reagan declaring, “I am a Contra.” I had consumed all of this as an innocent—and by writing poems I began issuing my declarations of independence.

Recently, I was reading the lectures that the novelist James Salter delivered at age ninety, at the University of Virginia, shortly before his death. In one of them, he quoted the French writer and critic Paul Léautaud, who wrote, “Your language is your country.” Salter added, “I’ve thought about it a great deal, and I may have it backwards—your country is your language. In either case it has a simple meaning. Either that your true country is not geographical but lingual, or that you are really living in a language, presumably your mother tongue.” When I read those words, I thought of my grandmother, who died a few years after I came to America. She was the only person to whom I wrote letters in my mother tongue, Hindi. On pale blue aerograms, I sent her reports of my new life in an alien land. Although she could sign her own name, my grandmother was otherwise illiterate and would ask the man who brought her the mail in the village or a passing schoolchild to read her the words I had written. And when my grandmother died, I had no reason to write in Hindi again. Now it is a language that I use only in conversations, either on the phone, with my friends and relatives in India, or, on occasion, when I get into cabs in New York City.

At another point in his lectures, Salter told his audience that “style is the entire writer.” He said, “You can be said to have a style when a reader, after reading several lines or part of a page, can recognize who the writer is.” There you have it, another definition of home. In novels such as “A Sport and a Pastime” and “Light Years,” the sentences have a particular air, and the light slants through them in a way that announces Salter’s presence. All the writers I admire, each different from the other, erect structures that offer refuge. Consider Claudia Rankine. You are reading her description of a woman’s visit to a new therapist. The woman has arrived at the door, which is locked. She rings the bell. The therapist opens the door and yells, “Get away from my house. What are you doing in my yard?” The woman replies that she has an appointment. A pause. Then an apology that confirms that what just happened actually happened. If you have been left trembling by someone yelling racist epithets at you, Rankine’s detached, near-forensic writing provides you the comfort of clarity that the confusion of the therapist in the poem does not.

Thirty years have passed since I left India. I have continued to write journalism about the country of my birth. This has allowed me to cure, to some degree, the malady of distance. I’ve reflected a great deal on the literature that is suited to describing the conditions in the country of my birth. But I have also known for long that I no longer belonged there.

I haven’t reported in grand detail on rituals of American life, road journeys or malls or the death of steel-manufacturing towns. I think this is because I feel a degree of alienation that I cannot combat. I’ve immersed myself in reading more and more of American literature, but no editor has asked me to comment on Jonathan Franzen or Jennifer Egan. It is assumed I’m an expert on writers who need a little less suntan lotion at the beach. I don’t care. Removed from any intimate connection to a community or the long association with a single locale, my engagement with literature is now focussed on style. Do my sentences reveal once again the voice of the outsider, a mere observer?

In a cemetery that is only a few miles away from my home, in the Hudson Valley, is the gravestone of an Indian woman. The inscription reads, “Anandabai Joshee M.D. 1865-1887 First Brahmin Woman to Leave India to Obtain an Education.” Joshee was nine when she was married to a twenty-nine-year-old postal clerk in Maharashtra, and twenty-one when she received a medical degree in Pennsylvania. A few months later, following her return to India, she died, of tuberculosis, at the age of twenty-two. Her ashes were sent to the woman who had been her benefactor in the U.S., and that is how Joshee’s ashes found a place in Poughkeepsie. I’m aware that, when she died, Joshee was younger than I was when I left India for America. Involved in medical studies, and living in a world that must have felt immeasurably more distant than it does now, she probably didn’t have time to write poems or worry about style. I recently read that last year a crater on the planet Venus was named after her. It made me think that brave Anandabai Joshee now has a home that none of us will ever reach.