In 2006, the British Library bought a huge archive of Angela Carter’s papers from Gekoski, the rare books dealer, for £125,000.It includes drafts, lots of them, a reminder that in the days before your computer automatically date-stamped all your files book-writing used to be a clerical undertaking. It has Pluto Press Big Red Diaries from the 1970s, and a red leatherette Labour Party one, tooled with the pre-Kinnock torch, quill and shovel badge. There are bundles of postcards, including the ones sent over the years to Susannah Clapp, the friend and editor Carter would appoint as her literary executor, which formed the basis of the memoir Clapp published in 2012; there’s also one with an illegible postmark, addressed to Bonny Angie Carter and signed ‘the wee spurrit o’yae Scots grandmither’. And there are journals, big hardback notebooks ornamented with Victorian scraps and pictures cut from magazines, and filled with neat, wide-margined pages of the most nicely laid-out note-taking you have ever seen. February 1969, for example, starts with a quote from Wittgenstein, then definitions of fugue, counterpoint, catachresis and tautology. Summaries of books read: The Interpretation of Dreams, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, The Self and Others. All incredibly tidy, with underlinings in red. And exploding flowers and nudie ladies stuck on the inside cover, as if in illustration of The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman, which Carter would have been working on at the time.

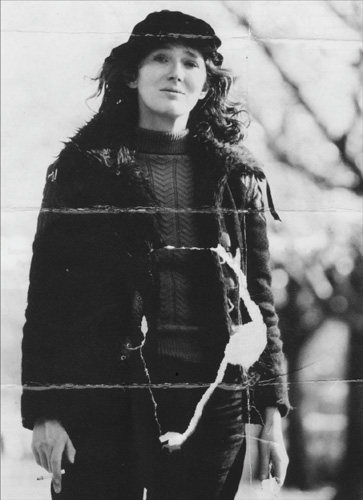

What was I looking for when I went to look at the Angela Carter Papers? To begin with I didn’t really know. Partly it was professional completism. Journalists are supposed to do as much research as possible, so it was part of the job, I decided, to take a look at this amazing public resource. Partly there was something cultic about it. There aren’t many places I love more than I love the British Library or writers I love more than I love Angela Carter, so of course I was going to take this chance to sniff at the sacred stationery, served on huge wooden trays by hushed BL staff. But mostly I was looking for an approach. Carter was 51 and at the height of her fame and family happiness when she died in 1992. Her instructions for the work she left behind were that it should be used in any way possible – short of falling into the hands of Michael Winner – ‘to make money for my boys’: Mark Pearce, her second husband, and Alexander, the couple’s son, born in 1983.

As Edmund Gordon says towards the beginning of his biography, Carter was never so widely acclaimed in life as she would be in the weeks and years after her death. The tributes were long, sometimes fulsome, always affectionate, and full of great table talk and funny stories from Carter’s ‘flotillas’ – Carmen Callil’s word – of famous friends. That happens when a well-liked person dies before their time, especially when the death has the long lead-in afforded by cancer treatment, and when they leave a younger partner and small child. It’s probably why Clapp’s memoir feels a bit overstuffed as it gets started. All those cats and birds and scarlet skirting boards, as if to hide and plug the hissing hole.

(…)

The Invention of Angela Carter: A Biography is published by Chatto & Windus (£25.00)