Patricia Lockwood on Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy, for the London Review of Books.

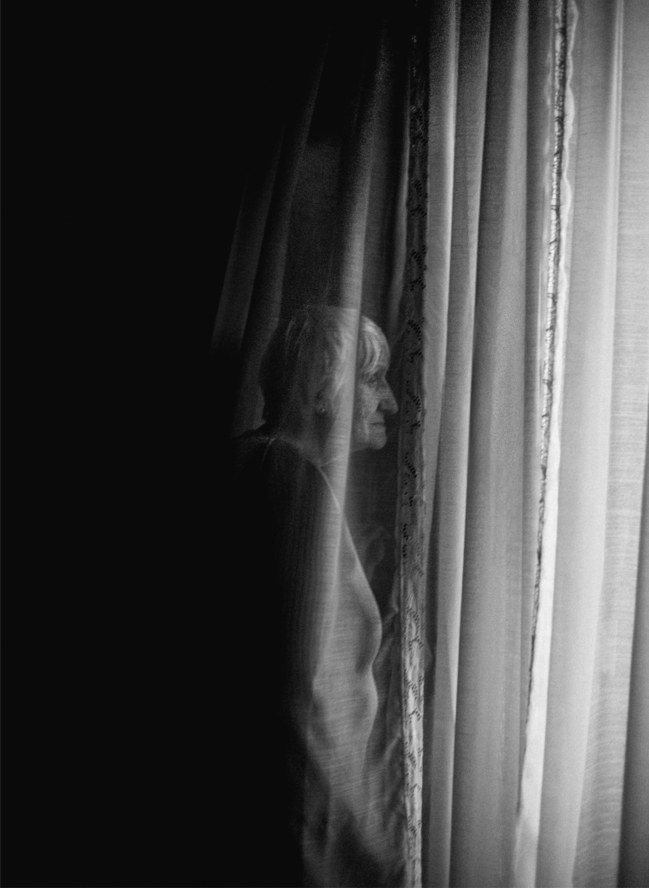

The observation that some people do not like Rachel Cusk is so omnipresent in criticism of her work that it’s surprising no one’s ever led off a review with ‘I, too, dislike her.’ These observations are generally accompanied by photos or illustrations of her in which she looks at you both directly and flinchingly, almost always with a strand of hair in the centre of her forehead, with a smile somewhat like Edna O’Brien’s – another writer who seemed to rouse hatred for her disarranged hair as much as for her books, another writer who went to convent school. This is the sort of education that can unfit you afterwards for normal conversation, that can make the suburbs seem beyond your power of understanding as you drive home past them from the locked-in place. You suspect that even from the other side of the frame she is noticing you, and people who notice are inconvenient, if not uncivilised. It would, after all, be uncomfortable to be on a ferry with Cusk as she visibly or invisibly observed that you had the ‘face of a withered Memling damsel’. That is, in the language of one of the places where Cusk grew up (LA), ‘way harsh, Tai’.

Cusk has glimpsed the central truth of modern life: that sometimes it is as sublime as Homer, a sail full of wind with the sun overhead, and sometimes it is like an Ikea where all the couples are fighting. ‘I wonder what became of the human instinct for beauty,’ she writes in The Last Supper, ‘why it vanished so abruptly and so utterly, why our race should have fallen so totally out of sympathy with the earth.’ A line like this is both overwrought and what I think myself when I look at these scenes. Why must we live in these places? Why must these be our concerns? Why do I have to know what McDonald’s is? It is a dissociate age and she is a dissociate artist. She is like nothing so much as that high little YouTube child fresh from the dentist, strapped into a car going he knows not where, further and further from his own will. Where is real life to be found? Is this it?

An anecdote: when I was a teenager a doctor prescribed me pills for anxiety, and when I stopped taking them abruptly I experienced a severe and unexpected and prolonged withdrawal. During that time I hated everything I read to a degree that I cannot reread those books now, or even think of them dispassionately. The feeling in my brain was like the one you have when you’re climbing the stairs and are expecting another step and you set your foot down so hard on nothing that reality ruptures. ‘This is my house,’ I had to say when I entered my house; ‘this is my bedroom,’ I had to say when I entered my bedroom. Reading Cusk I have that feeling all the time. When I came to the line in her memoir, Aftermath, ‘It is as though I’m expecting there to be a step down and there isn’t one,’ I was not so much surprised as relieved: she felt it too.

Outline landed with such a bang that it’s hard to believe it was published in 2014. Transit followed just two years later, written almost at the clip of reality. Now Kudos, just out from Faber, brings an end to the tremendously wilful project of these passive novels. In description nothing about them seems particularly out of the ordinary: each instalment is composed of a series of conversations – with strangers, with old friends and ex-lovers and her hairdresser, with her two sons. But as they unfold it becomes clear that they are fantasies in which the infinitesimal openings of small talk eventually drill down to the centre of the earth. What would happen if you let one of those cursory exchanges, brief or irritating or banal, either way trespassing on your solitude and peace – what would happen if you just let it go on?

(…)