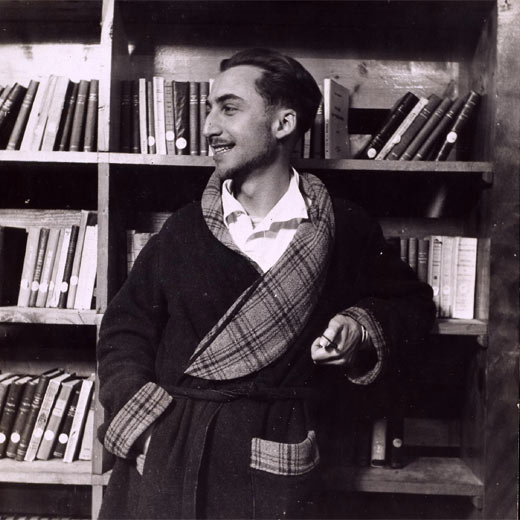

Brian Dillon on ‘growing up’ with Roland Barthes, in the Dublin Review:

1992

For a long time I sincerely believed I could not love a woman who was not well acquainted with Barthes’s writing. If this seems a bizarre criterion to apply to a prospective lover – all the more eccentric given my dismal prospects to start with – I think I can see now what I was hoping for. Theory in general, and my specific ambitions, had become a way of keeping the world at bay, an intellectual apparatus by which I thought to defuse potentially explosive emotional situations, or more accurately damp the slow-burning grief and general misery that I was unable to express. That much is obvious. What’s perhaps less clear is how much of desire and love and longing I’d also cathected into this stuff by my early twenties. It’s not that I simply wanted a lover who was super-smart and culturally cynical and much better read than I was; I wanted somebody infinitely sensitive and self-scrutinizing, also just as passive and debilitated as I was before the enigma of the Other. And this ideal relationship was obscurely related to central concepts or turns of thought and phrase in Barthes – a kind of abstracted perversity, lurid but nonviolent; a languid refusal of the role of sexual protagonist; a drifting between word and body, sex and Art, ideas and desire. I’d started to read Barthes as if his books, these works of ‘literary theory’, actually described a psychosexual utopia that was just out of reach. (It may be that this is exactly what they do describe.)

Such fantasies did not stop me from falling in love with people who had strictly no knowledge of or interest in the kind of books I was reading. And the ones who did had by no means taken things so much to heart. But like many an inarticulate young lover, I thought for a time that seduction was a matter of giving the right book to the right woman. In my case it was Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse: a meditation on Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther that catalogues the melancholic lover’s prized ‘image repertoire’ – the scene of waiting, the feeling of being dissolved in the presence of the loved being, the attraction of suicide – and thinly veils the author’s own life as a middle-aged gay man in Paris in the 1970s. This gift was always a prelude to disaster. The first time, the girl in question – she was a French waitress, of all things – left the country within days and never returned. The second, I found the book a month later under the girl’s bed, bearing the distinct imprint of a Doc Marten boot. The unlucky third time, the book was my idea of a Valentine’s Day present, and we split up weeks later. We split up again two years after that, by which time she’d got round to reading A Lover’s Discourse and wishing she’d never met me. Advice to the young: this book is brilliant and cursed.