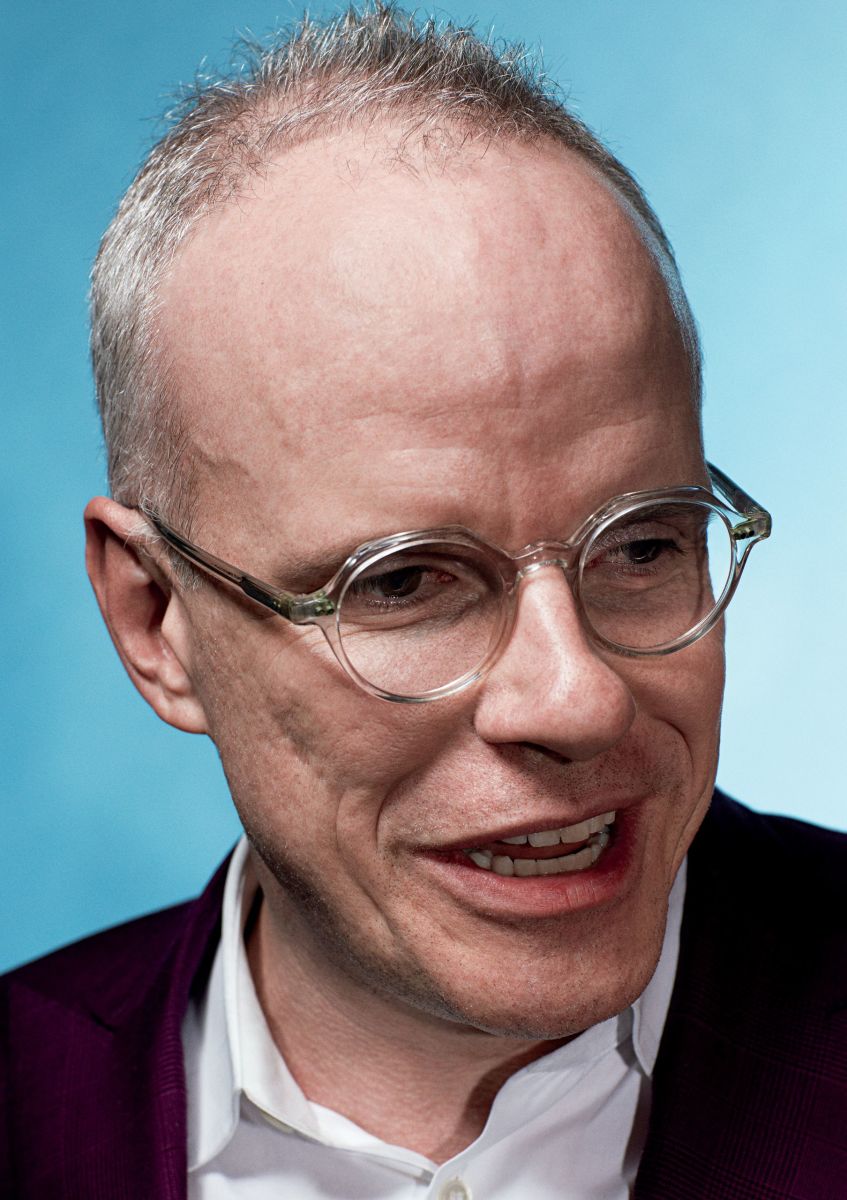

In the new issue of the New Yorker, D. T. Max, David Foster Wallace’s biographer, profiles Hans Ulrich Obrist. It’s a somewhat ambiguous portrait, with some back-handed compliments (from Ed Ruscha, for example). The story of how he started out is particularly impressive:

Obrist was born in Zurich and grew up in a small town near Lake Constance. His father was a comptroller in the construction industry, his mother a grade-school teacher. An only child, he found school “too slow,” and other Swiss found his vitality off-putting. “People would always say that I should go to Germany,” he remembered. His parents were not particularly interested in art, but on several occasions they took him to a monastery library in the nearby city of St. Gallen. He admired the antiquity of the books, the silence, the felt shoes. “You could make an appointment and, with white cloths, touch the books,” he said. “That’s one of my deepest childhood memories.”

When he was around twelve, he took the train to Zurich, where he fell in love with “the long thin figures” at a Giacometti exhibition. Soon he was collecting postcards of famous paintings—“my musée imaginaire,” he calls it. “I would organize them according to criteria: by period, by style, by color.” One day, when he was seventeen, he went to see a show by the artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss at a Basel museum. He was engrossed by their “Equilibrium” sculptures—delicately balanced metal-and-rubber constructions. He had been reading Vasari’s biographical sketches of the artists of the Renaissance, and it struck Obrist that he could try to meet creators, too. He reached out to Fischli and Weiss with this rap: “I’m a high-school pupil and I’m really, really obsessed by your work and I’d love to visit you.” He told me, “I really didn’t know what I wanted. It was just this desire to find out more.” Fischli and Weiss were amused by the precocious Obrist, and welcomed him to their Zurich studio. They were filming their now famous short film “The Way Things Go,” in which an old tire rolls down a ramp, knocking over a ladder and setting off a chain reaction. On his visit, Obrist discovered a sheet of brown wrapping paper on the floor with the entire Rube Goldberg schema drawn on it. “It was almost like a mind map,” he said.

Soon afterward, Obrist was entranced by a Gerhard Richter exhibition in Bern, and asked Richter if he could visit his studio, in Cologne. “That took courage,” he said. He travelled on the night train from Zurich. “When I arrived, he was working on one of his amazing cycles of abstract paintings,” Obrist said. They talked for ninety minutes. Richter was astonished by Obrist’s passion: “ ‘Possessed’ is the word for Hans Ulrich,” he told me. Richter recommended the music of John Cage. “We discussed chance in paintings and he said he liked playing boules,” Obrist recalled. A few months later, Obrist was in a Cologne park, playing boules with Richter and his friends.

Obrist doggedly arranged to meet other artists whose work he admired. He went to see Alighiero Boetti in Rome. The feverish Boetti may be the only person ever to complain that Obrist didn’t talk fast enough. (In his new book, Obrist writes with delight, “Here was someone with whom I had to struggle to keep up.”) When Obrist asked him how he could be “useful to art,” Boetti pointed out the obvious: that he was born to be a curator.

Obrist wasn’t sure what the job entailed, but he was intuitively drawn to the power of organizing art. As a teen-ager, he visited an exhibition at the Kunsthaus in Zurich: “Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk,” or “Tendency Toward the Total Work of Art.” It highlighted four selections from the past hundred years of modernism: Duchamp’s enigmatic glass construction “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,” and one painting each by Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Malevich. The works had been placed at the center of the Kunsthaus, heightening their effect. Obrist was struck by the intelligence of the man who had organized it: Harald Szeemann. Also a Swiss, Szeemann was one of several curators who had begun to bring a new inventiveness to the age-old job of selecting art to illustrate a theme. Obrist saw the show forty-one times. (Later, of course, he interviewed Szeemann.)

Obrist did not yet feel qualified to put his stamp on the art world. He had the autodidact’s anxiety about not knowing enough. For all his energy, he was not a revolutionary; he was an accumulator of information. But how to find out what artists were doing? “There wasn’t then a place to study,” he said. “I knew of no curator schools.” So he designed his own education. He enrolled at the University of St. Gallen, and majored in economics and social sciences. When not in class, he set out to see as many shows as he could.

Switzerland is well situated if you want to make impulsive trips around Europe. Obrist spoke five languages: German, French, Italian, Spanish, and English. (His English was given a boost by Roget’s Thesaurus, and he still keeps a vocabulary list in a blue notebook that he takes with him—among the latest words are “forage” and “hue.”) He took the night train to avoid hotel bills and arrived in a city the next morning. “I would go to every museum and look and look again,” he remembered. Then he visited local artists. He found that he could improve his welcome if he brought news of what he had seen, plus other artists’ gossip and opinions. “I would go from one city to the next, inspired by the monks in the Middle Ages, who would carry knowledge from one monastery to the next monastery,” he said. At Boetti’s suggestion, he also inquired about unrealized projects, as every artist had some and felt passionate about them. Above all, he listened. “I was what the French call être à l’écoute,” he told me. His youthful intensity sometimes raised concern. Louise Bourgeois, after meeting the teen-age Hans Ulrich, sleep-deprived and suffering from a cold, called his mother in Switzerland and urged her to take better care of her son.

In 1991, Obrist, in his early twenties, finally felt ready. By then, he estimates, he had visited tens of thousands of exhibitions and knew more artists than most professional curators. He chose to hold his first show in the kitchen of his student apartment. “The kitchen was just another place I kept stacks of books and papers,” he recalled. The minimalist gesture seemed appropriate, both as a reaction to the engorged art market of the eighties and as a reflection of the economic slump across Europe. It was also a playful homage: Harald Szeemann had done an exhibit in an apartment.

The idea of the show was to suggest that the most ordinary spaces of human life, cleverly curated, could be made special. Among the friends he included was the French painter and sculptor Christian Boltanski. Under the sink, Boltanski projected a film of a lit candle; the flickering could be seen through the gap in the cabinet doors. “It was like a little miracle where you expect it least,” Obrist remembered. He publicized the exhibit through small cards and word of mouth; still, he was relieved that only thirty people came over the three months it was open. “I was still studying and couldn’t have coped with much more,” he said. Among those attending was a curator from the Cartier Foundation, a contemporary-art museum in Paris. Soon afterward, Cartier offered Obrist a three-month fellowship. Obrist took it, leaving Switzerland for good.

Obrist quickly became a figure on the European art circuit. He was a clearing house for news and relationships, and he was generous—no sooner had he met someone than he helped that person connect with others in his widening circle. If he stayed in a hotel, he cleaned out the postcards in the lobby and mailed them to everyone he could think of. “He had these big plastic bags,” Marina Abramović, who met him in Hamburg in 1993, recalled. “I always wanted him to empty them and list all that was inside. . . . He would have information of every single human being—every artist living in a favela!” She remembered him as astonishingly innocent, an adjective that many still use for him. Many artists saw his unchecked commitment as a counterpart to their own. The French artist Philippe Parreno said, “For me, there is no difference between talking to him and talking to other artists. I am engaged at the same level.” Obrist once conducted an interview with Parreno while driving him from the Dublin airport to Connemara, and became so deeply absorbed that he didn’t realize he was on the wrong side of the street.

Obrist continued to set up shows in unusual locations. He put on an exhibit of Richter’s paintings in the country house where Nietzsche wrote part of “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” and a show in a hotel restaurant where Robert Walser, the Swiss writer, used to stop during long walks through the mountains. A third took place in Room 763 at the Hotel Carlton Palace, in Paris, where Obrist was then staying. In one part of the exhibit, called “The Armoire Show,” nine artists created clothes for the closet. With Fischli and Weiss, he toured the Zurich sewer museum. “They had toilets and urinals on plinths and had never heard of Duchamp,” he marvelled. This inspired him to put together “Cloaca Maxima,” which featured art about lavatories and digestion. The show opened in 1994, in and around the Zurich sewers.