Simon Leys, the great essayist and sinologist, died in August. Ian Buruma’s piece on his essay collection The Hall of Uselessness is an indispensable introduction to the man and his work:

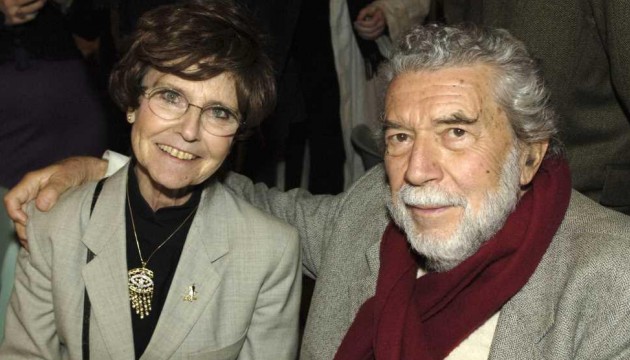

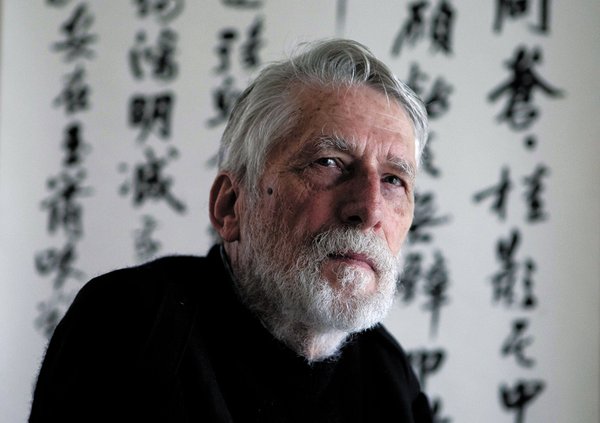

Simon Leys is actually the nom de plume for Pierre Ryckmans, a French-speaking Belgian with a Flemish name. He fell in love with Chinese culture when he visited China as part of a student delegation in 1955. After studying law at the Catholic university in Louvain, Leys became a scholar of Chinese, living for several years in Taiwan, Singapore, and in Hong Kong, where he made friends with a young Chinese calligrapher who, in a traditional flourish of stylish humility, named his own slum dwelling the Hall of Uselessness. Ryckmans spent two “intense and joyful years” there, “when learning and living were one and the same thing.” The name Leys is a homage to René Leys, the wonderful novel by Victor Segalen (1878–1919) about a seventeen-year-old Belgian who penetrated the mysteries of the Chinese imperial court just before the revolution of 1911.4

Ryckmans/Leys went on to become a highly distinguished professor of Chinese literature in Australia, where he still lives today, writing essays and sailing boats. Few, if any, contemporary scholars of Chinese write as well about the classical Chinese arts—calligraphy, poetry, and painting—let alone about European literature, ranging in this collection from Balzac to Nabokov. None, so far as I know, have written novels as good as his Death of Napoleon. Leys is perhaps unique in that his prose in English is no less sparkling than in French.

Unlike in the 1970s, few people now dispute that Leys was right about the horrors of Mao’s regime. Even the Chinese government admits that more than fifteen million people died of starvation as the direct result of Mao’s deranged experiments in the late 1950s. Recent scholarship shows that the real figure might be as high as forty-five million deaths between 1958 and 1962 (see Frank Dikötter’s Mao’s Great Famine, 2010). The Cultural Revolution, although Mao’s own leading role in it can still not be discussed openly, is commonly referred to as the “great disaster.” One of the questions raised by Leys is why most people got it so wrong when Maoism was at its most murderous. Was it a matter of excusable ignorance about what was then a very closed society?