Category: Fiction

Things That Didn’t Happen

Once upon a time, a woman and her husband lay together, and the man’s seed navigated the hollows and chambers of his wife’s body until it came home. Cells began to divide and re-form, as they do, and something new was made. As the weeks went by and the woman began to feel odd and sick, the new thing took shape: a comma, a tadpole, eventually the bud of a brain and a spinal column. Suddenly, in the shallow darkness of a summer night, a heart completed itself and began its iambic beat. The heart beat while the new thing grew a head and arms and legs, while it began to flutter and then to turn in the seas of the woman’s womb. For a long time the creature floated free, tumbling and kicking, learning to listen to the rumble of voices, to dance to music coming from the bright world beyond. When the woman swam, letting the water carry her swelling body, the growing being drifted and spun within her. When she walked the small thing was lulled by the percussion of her footsteps and the constant thrum of her heartbeat against its own, the engine of the ship bearing it on. But as winter passed and the sun strengthened on the ground where the woman walked, as the snowdrops and then the daffodils pushed through the earth and began to open apple-white and yolk-yellow, the creature found itself cramped. The walls of the womb seemed to close on its arms and legs, to wrap even its ribs and behind, and soon the being was pushed down, its head held in the woman’s bones and its hands and feet gathered in. The woman no longer swam. She walked less than she had, and she and the little stranger began to be sore and cross. At last, one bright April morning when white clouds drifted high in a blue sky and leaf-buds beaded the tired grey trees, it was time for the woman and the new thing to part, a painful work that took many hours, into the cold night and through the next morning, which the woman and her husband did not see because they were in a room with no windows, awaiting the child’s birth. The heart had been working for months now and it kept going, sometimes fast and sometimes slow, but always beating the same rhythm. Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting. When the child was born there came the ordinary miracle of breathing, that terrible moment when we are cast off from our mother and from her oxygenated blood, when we have never taken a breath and may not know how to do so, the caesura in the delivery room. She breathed. The music of heart and lungs began, and continued, and no-one listened any more.

[…]

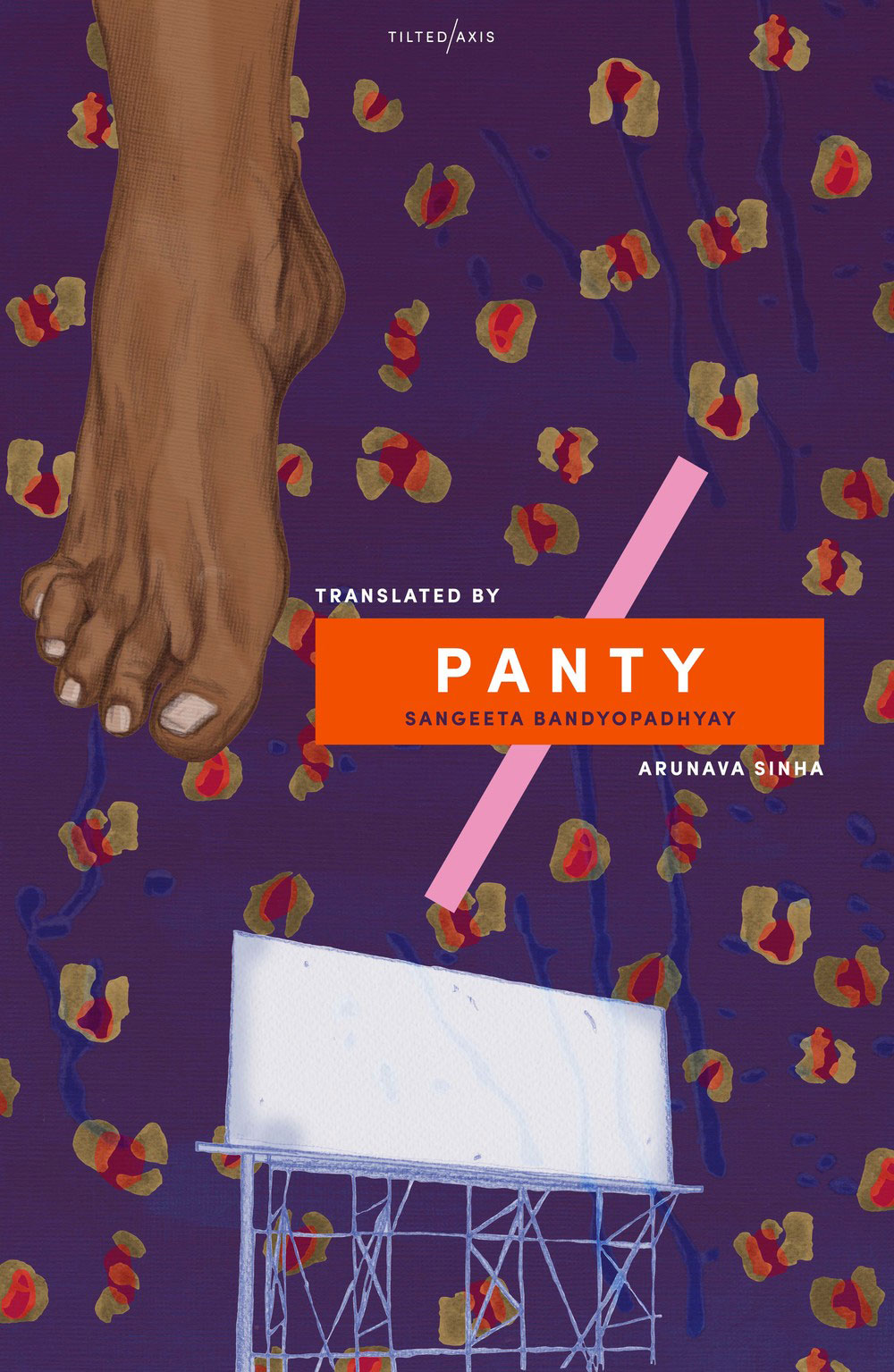

Panty

She was walking. Along an almost silent lane in the city.

Work – she had abandoned her work a long time ago, to walk. The sky had just turned a happy black.

As she walked, she mulled over two words – ‘legitimate’ and ‘illicit’. The presumption that these words were innate opposites – how totally were individuals expected to acquiesce to this! And yet the illicit held the greatest attraction for all that was legitimate.

Once, in an urge to ascertain the meanings of ‘legitimate’ and ‘illicit’, she had wished for a space that was at once one of emptiness and of equilibrium, the kind of space that defied the laws of nature. She had searched for such a space, but never found it.

Having walked for hours, when she came to her senses she discovered herself in the lane she was in now. And saw that the place was unfamiliar.

The lane was narrow and deserted, with ramshackle houses on either side. The bricks were exposed in the crumbling walls. The windowpanes were broken, and dirty water dripped from the pipes. Sucking out all the life force from this water, a banyan sapling had begun to rear its head. There were three or four antennae on the roof of every house in this lane full of potholes and crevices. Thousands of crows sat on the antennas. So many crows that the city would turn dark if they were all to spread their wings simultaneously.

Only a handful of rickshaws rattled by, some pulled by hand, some with pedals. There was the odd passer-by, humming, cigarette tip glowing. A dog whined at the sight of one of them. She was about mid-way down the lane when it was abruptly plunged into impenetrable darkness. A power cut had swooped down like a black panther, gobbling up the lane. Everything was annihilated by the killer paw of darkness.

She couldn’t decide what to do. Carry on? Go back? Both options appeared equally futile. She sensed the blindness even within her consciousness.

Surprised by her awareness of the extreme silence all round, a strange touch against her lips caused her to jump out of her skin.

Someone’s lips descended on hers; on the lips alone. They didn’t touch her anywhere else, the rest of her remained untouched and absolutely free; in the utter darkness an unknown pair of lips kissed hers deeply. A mild pain of being bitten and mauled, the warmth, the saliva, and the fire of an unfamiliar ache spread across her lips as one.

A kiss! A kiss! A kiss! She felt the kiss right down to its roots. So this was a kiss? So this was a kiss, when it was detached from the rest of the body? When – completely dissociated from the heart, from the consciousness, from even the obstacle of knowledge – a pair of lips united with another? When it was the coming together only of two pairs of lips? An isolated union?

In that darkness, the disembodied lips filled her lips, her tongue and the fleshy cavity of her mouth with the taste of the kiss, and she stood erect, savouring this novel feeling. She was hooked. When the lips left her, ending the kiss, the first sensation that returned was of sound. She heard, in turn, the sound of metal being hammered, of bus wheels rotating, of anklets jingling in a nearby house. The street lamps snapped back on, and the movement of people resumed. A dog howled.

She wanted to cry. She stood there for a long time, pressing her fingers to her lips. All this time, she’d thought she knew what a kiss was. Just as she’d thought she knew what love was, what the body was, what art was. When in fact she had known none of these.

She resumed her slow walk to the bottom of the lane. And then, as she turned the corner onto the main road, the meaning of ‘illicit’ became clear to her.

She had returned to the same lane many times since then, always just as dusk descended. There she would stand still and wait for the lights to go out, for a kiss to swoop down on her.

Interview with Han Kang

Han Kang is a disquieting storyteller who leads the reader into the very heart of human experience, where the singular crosses the universal. Author of ten books of fiction and poetry in her native Korean, Han’s subversive work has been brought onto the Anglophone stage through close partnership with her award-winning translator Deborah Smith. Smith’s elegant renditions of the novels HUMAN ACTS (2016) and THE VEGETARIAN (2015) form part of a recent blossoming of international interest in Korean literature; Dalkey Archive’s Library of Korean Literature launched in 2013 and consists of 25 translations so far. Originally published as three novellas in South Korea nearly a decade ago, Han has said that THE VEGETARIAN was initially received as ‘very extreme and bizarre’ in Korea. It has since become a cult bestseller, with translation rights sold in twenty countries and its central novella ‘Mongolian Mark’ awarded the prestigious Yi Sang Literary Prize in 2005. HUMAN ACTS, her latest novel, was awarded the Korean Manhae Literary Prize last year, adding to her numerous other accolades.

‘I believe that humans should be plants.’ This line from the great modernist poet Yi Sang, written in the Korean script hangul banned under Japanese rule, reportedly obsessed Han during university and became the seed for THE VEGETARIAN. Yi’s dream-like images evoking the violence of imperialism upon the colonial subject are mirrored in Han’s surrealistic and painterly portrayal of a woman’s personal rebellion. The novel tells the story of Yeong-hye who, haunted by grotesque dreams, first gives up meat, then food altogether in a radical refusal of human cruelty and destruction. In a patriarchal society where vegetarianism is rare, Yeong-hye’s transgression eventually leads to her institutionalisation and force-feeding. Han’s life-long exploration of the themes of violence and humanity are here rooted in the anorexic body forming a provocative psychological portrait of a woman’s body politics.

HUMAN ACTS revisits these themes but pans out to the national stage, excavating the traumatic legacy of the Gwangju massacre in post-war Korean history. Opening in the Gwangju Commune, the action unfurls in the crucible of the 1980s student and worker-led democratic movement. In 1979 when military dictator Park Chung-Hee, the father of current president Park Geun-Hye, was assassinated his ‘protégé’, General Chun Doo-Hwan, succeeded him and extended martial law across the country, closing universities, restricting press freedom and banning political organising. On 18 May 1980 when students gathered in Gwangju to protest these measures, the government responded by sending in soldiers who opened fire on the crowds. A citizen army managed to eject the military presence and in the following days virtually the whole city joined together in creating an autonomous community comparable to the Paris Commune. The uprising endured for a few days until it was crushed by a US-approved military operation on 27 May that killed and injured thousands.

The massacre left a deep imprint in Korea’s cultural memory, in part because the truth around events was suppressed for years afterwards. Conservative accounts painted the incident as a Communist plot driven by North Korean sympathisers, and the death toll remains contested. ‘Gwangju’, Han says, has become another word ‘for all that has been mutilated beyond repair. The radioactive spread is ongoing.’ Thus HUMAN ACTS is a book with a banging door – it is fiction as a form of alternative historiography where the unresolved past pollutes the present. For Han, ‘Gwangju’ functions like a common noun denoting mankind’s capacity for acts of extreme violence in the same instance as acts of great humanity. Indeed, Korea’s tumultuous history has seen a succession of Gwangjus: there has been little closure, for example, for the Korean women forced into sexual slavery under Japanese colonial rule, or for the families separated by the Korean War that left the two Koreas divided by the Demilitarized Zone when the Cold War turned hot on the peninsular.

A language carries its culture on its back and Han deftly transports the myriad complexities of Korean history through her spare prose. Yet HUMAN ACTS, likeTHE VEGETARIAN, is often about the failure of language to adequately convey experience. In a striking scene, a survivor of torture asks, ‘Would you have been able to string together a continuous thread of words, silences, coughs and hesitations, its warp and weft somehow containing all that you wanted to say?’ Han certainly attempts to do so, both in her lyrical work and in this interview, conducted through email and translated by Deborah Smith.

Q. THE WHITE REVIEW — The history of Korea in the twentieth century is rich in trauma – why did you choose to write about the Gwangju Uprising in particular?

A. HAN KANG — The twentieth century has left deep wounds not only on Korea but on the whole of the human race. Because I was born in 1970 I experienced neither the Japanese occupation, which lasted from 1910 to 1945, nor the Korean War, which began in 1950 and was concluded with a cease-fire in 1953. I began to publish poetry and fiction in 1993, when I was twenty-three; that was the first year since the military coup d’état in 1961 that a president who was not from the army but a civilian came to power. Thanks to that, I and writers of a similar generation felt that we had obtained the freedom to investigate the interior of the human without the guilty sense that we ought instead to be making political pronouncements through our work.

So my writing concentrated on this interior. Humans will not hesitate to lay down their own lives to rescue a child who had fallen onto the train tracks, yet are also perpetrators of appalling violence, like in Auschwitz. The broad spectrum of humanity, which runs from the sublime to the brutal, has for me been like a difficult homework problem ever since I was a child. You could say that my books are variations on this theme of human violence. Wanting to find the root cause of why embracing the human was such a painful thing for me, I groped inside my own interior, and there I encountered Gwangju, which I had experienced indirectly in 1980.

[…]

‘Running Away’

CHAPTER ONE

Would it ever end with Marie? The summer before we broke up I spent a few weeks in Shanghai, but it wasn’t really a business trip, more a pleasure junket, even if Marie had given me a sort of mission (but I don’t feel like going into details). The day I arrived in Shanghai, Zhang Xiangzhi, a business associate of Marie’s, was there to meet me at the airport. I’d only seen him once before, in Paris, at Marie’s office, but I recognized him immediately, he was talking to a uniformed police officer just past customs. He had to be in his forties, round cheeks, facial features swollen, smooth, copper-colored skin, and he wore very dark sunglasses that seemed too big for his small face. We were waiting at the edge of the baggage carousel for my bag and we’d hardly exchanged a few words in broken English before he handed me a cell phone. Present for you, he told me, which plunged me into a state of extreme bewilderment. I didn’t really understand why he felt the need to give me a cell phone, a used cell phone, rather ugly, dull gray, without packaging or instructions. To keep an eye on me, be able to locate me at any time, watch my every move? I don’t know. I followed him silently through the airport terminal, and I felt a sense of unease, heightened by jet lag and the tension that comes with arriving in an unknown city.

On exiting the airport, Zhang Xiangzhi made a quick gesture with his hand and a shiny new gray Mercedes slowly rolled up to us. He got in behind the wheel, sending the driver, a young guy with a fluid, scarcely noticeable presence, to the back seat after having placed my bag in the trunk. Seated at the wheel, Zhang Xiangzhi invited me to join him in the front, and I sat beside him on a comfortable, cream-leather seat with armrests and a new-car scent while he tried to adjust the air conditioning, which, after fiddling with a digital touch pad, began humming softly in the vehicle. I handed him the manila envelope that Marie had asked me to give him (which contained twenty-five thousand dollars cash). He opened it, thumbed quickly through the bundles to count the bills, then resealed the envelope before putting it in his back pocket. He fastened his seat belt and we left the airport slowly to get on the freeway in the direction of Shanghai. We didn’t say a word, he didn’t speak French and his English was poor. He wore a gray short-sleeved shirt and a small gold chain with a pendant in the shape of a stylized claw or dragon’s talon around his neck. I still had the cell phone he had given me, it was on my lap, I didn’t know what to do with it or why it had even been offered to me in the first place (just a Welcome to China gift?). I was aware of the fact that Zhang Xiangzhi had been overseeing Marie’s real-estate investments in China for a few years now, some possibly dishonest and illicit activities, renting out and selling commercial leases, purchasing building space in rundown areas, the whole thing probably tainted by corruption and all sorts of clandestine exchanges of money. Since her first bouts of success in Asia, in Korea and Japan, Marie had set up shop in Hong Kong and Beijing and had been hoping to acquire new storefronts in Shanghai and in the south of China, with plans underway to open branches in Shenzhen and Guangzhou. For the time being, however, I hadn’t heard anything about Zhang Xiangzhi being involved in organized crime.

On arriving at the Hansen Hotel, where a room had been reserved for me, Zhang Xiangzhi parked the Mercedes in the hotel’s private interior courtyard and went to grab my bag from the trunk before ushering me all the way to the front desk. He hadn’t been involved in any way with reserving the room, which was done from Paris by a travel agency (a one-week, fully planned “escapade” with hotel and flight included, to which I added an extra week of vacation for my own enjoyment), but now he was seeing to everything, having me step aside as he took care of the arrangements. He had me wait on a couch while he went alone to the front desk to check me in. I sat there waiting in the lobby, next to a depressing display of dusty plants withering in flowerpots, and I watched him listlessly as he filled out my registration information. At one point he walked over to me, hurried, concerned, his hand reaching out anxiously, to ask me for my passport. He walked back to the front desk and I kept an eye on my passport, watching it with some concern as it passed from hand to hand, worried that I might see it spirited out of the hands of one of the numerous employees shuffling behind the counter. After a few more minutes of waiting, Zhang Xiangzhi came back over to me with the magnetic key card for my room. It was enclosed in a red and white case adorned with carefully formed Chinese characters, but he didn’t give it to me, he kept it in his hand. He grabbed my bag and invited me to follow him, and we headed to the elevators to go up to my room.

It was a three-star hotel, clean and quiet, we didn’t see a single person on our floor, I followed Zhang Xiangzhi down a long deserted hall, an abandoned housekeeping cart blocked our way. Zhang Xiangzhi slid the magnetic card through the lock and we entered my room (very dark, the curtains were drawn). I fiddled with the light at the door but the dimmer switch turned without effect. I tried to turn on the bedside lamp, but there was no electricity in the room. Zhang Xiangzhi pointed at a little receptacle on the wall next to the door in which one was meant to insert the key card in order to turn on the electricity. To demonstrate, he slowly inserted the card into the little slot and all the lights lit up at once, in the closet as well as the bathroom, the air conditioner loudly began to emit cool air, and the bathroom fan turned on. Zhang Xiangzhi went to open the curtains and stood at the window for a moment, pensive, looking at the new Mercedes parked in the courtyard below. Then he turned back around, as if to leave-or so I thought. He sat down in the armchair, crossed his legs, and took out his own cell phone, and, without appearing to be inconvenienced in any way by my presence (I was standing in the middle of the room, exhausted from my trip, I wanted to shower and stretch out on the bed) he began dialing a number, closely following the instructions on a blue phone card that had the letters “IP” written on it, followed by various codes and Chinese characters. He needed to start over a couple of times before getting it right, and then, gesturing emphatically in my direction, he called me over, had me run to his side, so that he could hand me the phone. I didn’t know what to say, where to speak, to whom or in what language I would be speaking, before hearing a female voice say allo, apparently in French, allo, she repeated.Allo, I finally said. Allo, she said. Our confusion was now complete (I was beginning to feel uneasy). Marie? With his sharp and focused eyes aimed at me, Zhang Xiangzhi was prodding me to talk, assuring me that it was Marie on the line-Marie, Marie, he was repeating while pointing at the phone-and I finally understood that he had dialed Marie’s number in Paris (her office number, the only one that he had) and that I was talking to a secretary at the haute-couture house Let’s Go Go Go. But I didn’t feel like talking to Marie right now, not at all, especially in front of Zhang Xiangzhi. Feeling more and more uneasy, I wanted to hang up, but I didn’t know which button to push or how to stop the conversation, so I quickly tossed him the phone as though it were white-hot. He hung it up, brusquely snapped it shut, pensive. He retrieved it from his lap, brushed it on the back of his hand as if to dust it off, and leaned forward to hand it to me without leaving his chair.For you, he told me, and he explained to me in English that, if I wanted to make a call, I should always use this card, dial 17910, then 2 for instructions in English (1 for Mandarin, if I preferred), the card’s number, followed by his PIN, 4447, then 00 for international, 33 for France, and then the number itself, etc. Understand? he asked. I said yes, more or less (maybe not all the details, but I got the gist of it). If I wanted to make a call, I should always use this card-always, he insisted-and, pointing to the room’s old landline phone on the bedside table, he shook his finger, saying no forcefully, like an order or command. No, he said. Understand? No. Never. Very expensive, he said, very very expensive.

In the following days, Zhang Xiangzhi called me only once or twice on the cell phone he had given me to see how I was doing and to invite me to lunch. Since my arrival, I had spent most of my time alone in Shanghai, not doing much, not meeting anyone. I’d walk around the city, eating at random times and places, seasoned kidney skewers on street corners, burning hot bowls of noodles in tiny hole-in-the-wall places packed with people, sometimes more elaborate meals in luxurious hotel restaurants, slowly working my way through the menus in deserted kitsch dining halls. In the afternoon, I’d take a nap in my room, not going back out until nightfall when it would get a little cooler. I’d go for a walk in the mild night, lost in thought, strolling alongside the multicolored neon-lit shops of Nanjing Road, indifferent to the noise and constant activity. Drawn to the river, I’d always end up in the Bund, welcomed by its maritime atmosphere and sea breeze. I’d cross through the underground passageway and amble aimlessly along the river, letting my eyes fall upon the row of old European buildings whose green lights, reflected on the wavy water of the Huangpu, projected emerald halos in the night. From the other bank of the river, beyond the flow littered with vegetable waste stagnating in the darkness, beyond the chunks of mud floating on the surface of the water and the algae magically held in place by an invisible undertow, the skyscrapers of Pudong traced a futuristic line in the sky as fateful as the lines that mark our palms, punctuated by the distinctive sphere of the Oriental Pearl, and, further along on the right, as if in retreat, modest and hardly lit up, the discreet majesty of the Jin Mao Tower. Looking out at the water, pensive, I was captivated by the river’s dark and wavy surface, and in a state of dreamlike melancholy-as often happens when the thought of love is met with the spectacle of dark water in the night-I was thinking about Marie.

Was it already a lost cause with Marie? And what could I have known about it then?

[…]

‘The Emperor’s Mantle’

Here’s an extract from an extract of Álvaro Enrigue’s novel Sudden Death, published earlier this year by VICE and described by the magazine’s culture editor, James Yeh, as ‘one of the most engaging, audacious, and flat-out fun works of fiction I’ve read in a while’:

Don Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin, Nahua of noble birth and master featherworker, was at his shop in San José de los Naturales—once a farm of exotic birds under the Emperor Moctezuma—when he met Vasco de Quiroga. They were introduced by Fray Pedro de Gante, who managed what was left of the totocalli (as such farms were called) after the brutal years of the invasion.

The lawyer and the featherworker were soon on a comfortable footing, since both were of noble birth, both had been part of imperial courts in their youth, both had remained—over the 12 most confusing years that their two vast and ancient cultures had known in who knows how many centuries—in the unusual situation of actually being free.

Vasco de Quiroga had no reason to return to Spain and was greatly excited by the idea of building a society on rational principles. The Indian had nowhere to go back to, but he had managed to find a relatively secure and comfortable spot for himself after years of darkness, misery, and fear. His aristocratic rank was respected and his work was so admired that most of the pieces made in his shop were sent immediately to adorn palaces and cathedrals in Spain, Germany, Flanders, and the duchy of Milan.

Unlike most Mexicans, Don Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin did know what this meant: He had been to Europe. He belonged to the select group of highborn artists who were received by the Holy Roman Emperor on Cortés’s first trip back to Spain, and he knew very well that the new lords of Mexico might be eaters of sausage made from the blood of pigs, but they were also capable of rising far above their barbaric ways when it came to building palaces, painting canvases, cooking animals, or—and this impressed him most of all—making shoes.

From the moment that the ship he had been obliged to board (though not herded onto like cattle) sailed out of sight of American lands, Huanitzin realized that in order to survive his new circumstances he would have to learn Spanish. By the time they arrived in Seville, after stops in Cuba and the Canary Islands, he was attempting polite phrases in the language of the conquistadors and was able to say that he and his son would be happy to make a heavy cloak of white feathers for His Majesty: The sailors had told him that Spain was known for being cold.

Cortés loved the idea of the featherworker and his son making a small demonstration of their art in court—he himself had a spectacular feather mantle on his bed at his house in Coyoacán showing the birth of water in springs and its death as rain—and he immediately gave Huanitzin favored status among his entourage. Not only did the featherworker speak Spanish—terrible Spanish, but he could make himself understood—he was the only one who seemed to show any interest in taking stock of his new circumstances.

Once in Toledo, the conquistador arranged for a workshop to be set up next to the palace stables and negotiated unrestricted access to the kitchen, where the preparation of ducks, geese, and hens afforded Huanitzin a sufficient supply of feathers to make a cape for an emperor who, the featherworker was beginning to understand, had defeated the Aztec emperor because he was infinitely more powerful, even though he lived in a dark, drab, and icy city.

After setting him up in his new shop and providing him with satin, glue, paints, brushes, tools, and the assistance of the royal cooks, Cortés asked Huanitzin what else he needed in order to pay tribute to the emperor. Shoes, he replied. What kind, asked the conquistador, imagining that he must be cold and want woolen slippers. Like yours, said Huanitzin—who, being an Aztec noble and a featherworker, considered a provincial squire turned soldier to be of a class beneath his. With cockles. Cockles? asked Cortés. The Indian pointed to the captain’s instep, festooned with a golden buckle and inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Buckles, said the conquistador; shoes with buckles. That’s it.

Naturally, Cortés didn’t buy Huanitzin a pair of shoes stitched with silver thread like his—not only were they monstrously expensive, walking in them was like squeezing one’s toes into a pair of flatirons—but he did buy him good high-heeled boots with tin buckles, and along with them a pair of stockings, a few white shirts, and a pair of black breeches intended for some nobleman’s son that fit the featherworker like a dream.

The Indian accepted the garments as if they were his due—without paying them much attention or thanking him for them—and made one last request of the conquistador before getting to work: Could you also find me some mushrooms? Mushrooms? To see mellifluous things while I’m worrying the king’s drape. It’s called a royal cape, a capón real. I thought that a capon was a bird with its burls cut off. Balls. Not balls, it’s mushrooms I want. Here they would burn us both if they discovered you drunk on mushrooms. I’d hardly be dunked in them, it’s not as if they’re a pond. There are none in Spain. Well then, the royal capón won’t be as mellifluous.

Huanitzin liked his new clothes, though he didn’t think them fitting for a master featherworker who was once again on the grounds of an emperor’s palace, so he used his first Spanish goose feathers to embroider one of the shirts—the one he wore on special occasions—with pineapples that he imagined were the equivalent of the Flanders lions he’d seen worked in gold on Charles V’s cloak. The breeches were sewn down the side seams with bands of white feathers, turning him into a first wild glimpse of mariachi singers to come. The cooks spoiled this tiny man, who inspected their birds’ scrawny necks and armpits in a getup like a saint on parade. When he decided that a fowl was worthy of being plucked, he kneeled over it, took a pair of tiny tweezers from his sash, blew the hair out of his eyes, and defeathered the part of the bird that interested him with maddening care—the cooks knew by now that once he chose a specimen it would have to be moved to the dinner menu because there was no way he’d be done with it before lunch. Hours later, he would return happily to his shop, generally with a harvest of feathers so modest that it hardly filled a soup plate. Sometimes he looked over the birds and found none to be of interest—there was no way to predict which he would judge worthy material for the king’s cape. Other times it happened that there would be no birds cooked that day. When this was the case he still lingered in the kitchen, leaning on the wall so as not to be in the way. He admired the size of the chunks of animal moving on and off the hearth. What is that, he asked every so often. Calf’s liver. He would return to his shop to tell his son that the king was to eat castle adder that night. But what is it? Must be a fat snake that lives in ruined towers, he explained in Nahuatl.

[…]

Counternarratives by John Keene

Today is the publication day of John Keene’s Counternarratives. In honour of this, here is an extract from one of his short stories included in our edition:

THE AERONAUTS

Scream I holler to Horatio’s, Nimrod’s and Rosaline’s laughter, then they’re asking me to tell it to them again, though I plead how at this age I can’t hardly even remember my name. Horatio says, “Red, come on, just one more time cause you ain’t fooling us,” and I start with how it began six months before all that happened, round the middle of May, 1861, when I showed up for my job as a steward at the final Saturday of the spring lecture series at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. I had spent that morning toiling under my regular boss, Dameron, helping prepare for a grand dinner party he was catering for a Mr. Albert Linde, president of the Philadelphia Equitable Mutual Insurance Company, and was glancing up at the wall clock so often I nearly cut my thumbs off dicing rhubarbs. Dameron couldn’t afford an accident so he switched me over to kneading the bread and pie doughs, then had me stir the turtle soup stock. Finally he released me a little early with the promise that I’d be back promptly, at four o’clock. Dameron didn’t gainsay me earning a little extra from my side job, but he also had warned me more than once about my tardiness. Although I was no great cook, hated being in kitchens and hated even more ordering anyone around, catering was going be my profession, cause as my daddy used to say, “Anybody can cook a bad meal for theyself but rich folks always welcome help to eat well.”

I ran the eight blocks from Dameron’s to Orators Hall on Broad, where the Academy held its Saturday talks, and almost as soon as I slipped in the back door, I heard Kerney, the head of stewards, ringing his bell, calling us to order because the lecture was about to begin. I was completely out of breath but I immediately shucked off my dingy gingham trousers and brown cooking smock, and crammed myself into my uniform, which had belonged to Old Gabriel Tinsley till he came down stricken on Christmas the year before. The Prussian blue kersey waistcoat and trousers, still carrying his regular scent of wet cinders, were almost too tight on my thighs and backside. I mopped the sweat off my brow, knotted my gray cravat from memory, cause there wasn’t a mirror in the stewards’ dressing room, and hurried out to the main hall.

All of the other stewards, including my older brother Jonathan, were already finishing up their tasks, gliding between the reception room and the main hall. They had emptied and polished the brass bowls of the standing ashtrays, transferred the Amontillado sherry from the glass decanters into the miniature crystal glasses, and brushed the last specks of lint from the main serving table’s emerald baize cover. Jonathan nodded to me as several of the stewards began ushering the guests from the alcove to their seats, but I didn’t see Kerney though I had certainly heard that bell. Several gentlemen, members of the Academy and their guests, entered the hall and as I attempted to head over to guide each to one of the other stewards who would be seating them, I felt fingers winching round my forearm, like the claws of an ancient bird the Academy would probably exhibit, and sour breath warming my ear: “Boy, if you had walked through that door there even a second later I would thrown you out in the street myself! Late one more time and there won’t be no damn next time.”

I turned to see Kerney fixing me with his red-eyed stare. I could smell he had been tasting, or how he liked to say testing, the sherry, and probably had been tallying every second on the main hall clock’s little hand past the time I was supposed to walk through that door. I eased myself out his grip, his crisped apple face tracking me across the room, and took care not to look in his direction. Soon as I reached my assigned spot Dr. Cassin, the president of the Academy, Dr. Cresson, who ran the Franklin Institute, and the afternoon’s speaker, another professor I recalled from a prior lecture, took their seats, the customary hush settled over the room, and the five other stewards and I assumed our places. Shoulder to shoulder we lined up, erect as a row of tin soldiers, facing the lecture hall’s high, windowless, crimson wall. Stock still, thighs against the table edge, chins up, our white cotton-gloved right hands palm-down over the lowest button of our waistcoats, we were so quiet you could forget we were there.

In the front row next to Dr. Cassin, Dr. Cresson, the speaker, and the other Academy dignitaries sat as always almost completely out of my sight. The most recently hired of the crew, I had started only at the beginning of this year’s spring series, in February, through Jonathan’s intercession on my behalf with Kerney, and so I stood last in the row and farthest from the front of the room, though I could spot the dais and lectern. This month’s crowd was noticeably larger than in April. Thirty-six white gentlemen in the room I calculated, from the furthestmost chair in the front row to the nearest one in the last, whereas at the meeting the month before, which had unfortunately fallen on the same weekend as the attack on the South Carolina fort, starting the war, only twenty members and their guests showed up to hear the speaker, Professor Benjamin Peirce of Harvard. He had delivered a talk on his discovery that the rings of Saturn were not solid and how he had proved the other researchers wrong, and even if I had not learned enough mathematics or natural science at the Institute to follow him, I enjoyed his lecture, despite his talking so fast that he lullabied most of the audience to sleep.

Afterward as I brought my sherry tray around I passed by Professor Peirce talking to City Councilor Mr. Trego and Dr. Leidy, both members of the Academy; a guest I didn’t know; and Mr. Peter Robins, the son, not his father who ran the bank. As soon as he saw me young Mr. Robins started up the same “game” he had initiated every month since I had worked there, saying to his party, “I think Theodore here pays as much attention as we do,” as if he was expecting me to say something in reply, but I smiled and instead lifted the tray of sherry glasses higher. Mr. Councilor Trego looked around the room, Dr. Leidy whispered something to his guest, while the Harvard professor was looking at me all quizzically, then Mr. Peter Robins again said, “Theodore always pays close attention, don’t you, he’s a very sharp boy,” and I responded with another smile since I noted Kerney’s glares. Professor Peirce turned to the three white men and said very rapidly as he combed his fingers through his gray beard, “Certainly my lectures can be a bit dense even for those who have had the benefit of reading them in advance, and my astronomical work and other proofs provoke particular challenges,” to which Mr. Robins said, “Theodore, tell our distinguished guest one of the things you heard him speak about today.” At that moment Kerney I could see was turning red as tenderloin and looking like he was about to come slap me if I opened my mouth.

Before Mr. Robins, also reddening in the cheeks, could repeat his request I said, “Well, Sir, the professor was talking about the universality of physical laws and the uniformity with spiritual law too, and said at one point that every part of the universe have—has—the same laws of mechanical action as you find in the human mind.” Mr. Robins grinned and patted me on the head, and Mr. Councilor Trego and Dr. Leidy nodded approvingly, though Professor Peirce continued to stare at me like I was a puzzle. To break the silence I said, “May I take you gentlemen’s glasses?” After they turned to walk away young Mr. Robins pulled out some coins and placed them in my hand, saying, “A special tip for your far more amusing contribution to our series.” When he caught up to Professor Peirce, who had joined another nearby group, the Professor once again spoke, his words gushing forth, “Isn’t that an articulate and clever little. . . .”

Not that I can truly recall everything unless I am paying attention, and my mother was always warning me about allowing my memory or the past to overmaster me, let things go she would say, just like she would admonish me not to let my mind fly too far, too fast into such things, lest I couldn’t bring it back down to earth, because, as she was fond of saying and my father was too, “Outside the most exalted leaders of our race what sort of life you think there is for us if our heads stay too far up in them clouds?” and if anything has to do with the clouds it’s mathematics and astronomy and so forth, which unlike history or literature I had never disliked, and I wasn’t too bad at figures, plus if you think about it, even I could see from all the preaching I had to sit through that the cloud talk also had to do with religion, which is what I also think Professor Peirce was saying but I couldn’t tell nobody there that, all they were trying to do at those lectures was figure out how things of this world and the next one worked but also to see if, outside of a church, they could reason Him out, and thinking about that reminded me of how when I was little I used to like to spend my Saturday afternoons reading about science and strange places and looking at the maps at the Free Library, which we too were allowed to visit, and I will never forget seeing a book on display there by Mr. Audubon, about whom Dr. Cassin, who was also a famous ornithologist, gave the lecture the month before Professor Pierce’s.

[…]

My Life

I have a house, and it’s great. My money bought it, so it’s mine. I love to live in it. Never yours, always mine.

I have sex with a man, my husband. It’s great. We do it a long time. It feels good. A great time.

My mother comes to visit. She lives somewhere else. I came out of her vagina.

My job is at an office. I do it with a computer. It’s a lot of work. For one half hour I eat lunch.

I wear dresses, because I’m a woman. I also wear a bra, underpants, stockings, high-heeled shoes, a ring, a coat, a hat, and something else I’m forgetting right now. Eyeglasses. When I go inside my work

I take off the coat, the hat, and one time my shoes, but never all the other things.

My father was a man, and my mother is a woman.

My father is dead. His body was put into a coffin, and the coffin was put into the ground. He will be there until the end of time.

I am thirty-four years old. There are gray hairs on my head and wrinkles on my brow. I do a diet and jog around the track. I wear makeup on my face, such as lipstick.

Sometimes I hear voices, and they make me scared. The voices are in books, on television, on the radio, in the computer, and sometimes in a real person. They are different voices than my own. I’ve seen more dead bodies than most people I know.

Forget about the future, the past is what’s great. I remember the past, and I tell people about it in stories. My stories never include the future, which hasn’t happened yet.

When my father died from an illness, people said, “I’m sorry.” My friend said, “Take it one day at a time.” When I was younger I thought these were dumb words because lots of people had said them before, but now I think that these are smart words because lots of people have said them before. When he stopped breathing, I cried dozens and dozens of tears.

I have a dog named Meatball and a cat named Skinbag.

I am a light beige person. My hair is dark brown. My eyes are green. The bra I wear is for my breasts, which grew when I was a teenager. I also grew hair on my vagina and other places. Children can be distinguished from adults by their inferior height.

Some of my hairs I pull out. Hair is ugly—better to be shiny and smooth.

God lives inside a church, and he tells me that everything is great.

I had a wedding in a beautiful building. My dress was white and admired by everyone. A ceremony, rings, kissing, a toast, eating, speeches, and dancing happened. After my husband and I left, someone executed clean-up maneuvers.

My car is white and great. My husband has a vehicle too—green. We wear our seat belts when we drive and turn the steering wheels.

A child came out of my vagina. It was small and crying. Sometimes it was quiet. Later it grew. I sang so it would go to sleep and gave it milk. There were a lot of diapers. It was a girl.

Last week I put cheese and crackers on a tray. I bought wine. Lots of people came over. Music was playing. It was a great party.

My husband is in the garage kissing the babysitter. I pay the babysitter money to watch my child when I go to the office or to other people’s great parties. I am full of anger, but that’s okay.

Just kidding! Everything I’ve told you is a lie.

…

Drone

1

It is, of course, the tallest tower. In the slums below, people orient themselves by it as they carve their way through the warren of chawls. Rich men have been building tall on this hill for centuries, but no one will ever reach as high again. The owner of this hundred-storey pinnacle has bought the air rights around its peak, for sums so vast that the men who own the adjacent fifty- and sixty-storey erections feel quite sanguine about the cap he has placed upon their desires.

For now. Perhaps ever is too strong a word.

This is the house of the Seth, who has learned, in his century and a half of life, to appreciate the beauty of layering. A man of taste knows that when you change, you should always leave a trace. The common people have short memories. One needs to remind them, to keep things before their eyes.

Eighty years ago, when he built his house, the Seth loved Italy. He loved, in particular, the rolling hills and cypress trees of Tuscany as they appeared in the background of portraits of aristocratic Renaissance warlords. He owned pictures like this and saw no reason he shouldn’t go further. He had no interest in physically occupying any part of Tuscany, or indeed anywhere else in blighted Europe. It was the fantastical chivalric Tuscany of the portraits he desired. Urbino, as he called his house, was to be both a landscape and a castle within that landscape, a crag with a view of a palace and a palace with a view of a crag. A waterfall would tumble down its sides. And so it rose, the work of one of the great perspectival architects of the era, four impossibly elongated Palladian facades, which, from the point of view of the neighbours (and the shack-dwellers far below), broke into passages of Italian landscape, incorporating flocks of birds and a cataract that gushed white water. In certain weather conditions, a line of robed angels modelled on the Seth’s third wife could be seen ascending a set of spiralling golden stairs.

The apsara house, the slum boys called it. The sexy-sexy house.

Later, the political climate changed. Italy was not the sign of a true patriot, a real Indian. Unlike a lesser man, who would simply have pulled the thing down and built again, the Seth melted Urbino, like an ice sculpture left out in the sun, impressing the new order onto the upper floors. On top of the old palace, now angel-less and renamed Adityavarnam, is a Sun Temple built of red sandstone, in the shape of a chariot with a high-pointed shikhara and massive carved wheels. A saffron flag flutters at its peak. Below it, on the middle floors, are the quarters of the earthly members of the Seth’s household. The lower storeys, a maze of slimy rock and rotting Italianate columns, contain garages for his vehicles and giant kitchens for festival days, on which it is the Seth’s custom to feed the poor.

(…)

Seiobo There Below

Over at The White Review, the first chapter of László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below, ‘Kamo-Hunter’, translated by Ottilie Mulzet. Originally published in English by New Directions in the US, it’s forthcoming from Fitzcarraldo Editions Tuskar Rock Press in the UK in 2015.

1

KAMO-HUNTER

Everything around it moves, as if just this one time and one time only, as if the message of Heraclitus has arrived here through some deep current, from the distance of an entire universe, in spite of all the senseless obstacles, because the water moves, it flows, it arrives, and cascades; now and then the silken breeze sways, the mountains quiver in the scourging heat, but this heat itself also moves, trembles, and vibrates in the land, as do the tall scattered grass-islands, the grass, blade by blade, in the riverbed; each individual shallow wave, as it falls, tumbles over the low weirs, and then, every inconceivable fleeting element of this subsiding wave, and all the individual glitterings of light flashing on the surface of this fleeting element, this surface suddenly emerging and just as quickly collapsing, with its drops of light dying down, scintillating, and then reeling in all directions, inexpressible in words; clouds are gathering; the restless, jarring blue sky high above; the sun is concentrated with horrific strength, yet still indescribable, extending onto the entire momentary creation, maddeningly brilliant, blindingly radiant; the fish and the frogs and the beetles and the tiny reptiles are in the river; the cars and the buses, from the northbound number 3 to the number 32 up to the number 38, inexorably creep along on the steaming asphalt roads built parallel on both embankments, then the rapidly propelled bicycles below the breakwaters, the men and women strolling next to the river along paths that were built or inscribed into the dust, and the blocking stones, too, set down artificially and asymmetrically underneath the mass of gliding water: everything is at play or alive, so that things happen, move on, dash along, proceed forward, sink down, rise up, disappear, emerge again, run and flow and rush somewhere, only it, the Ooshirosagi, does not move at all, this enormous snow-white bird, open to attack by all, not concealing its defenselessness; this hunter, it leans forward, its neck folded in an S-form, and it now extends its head and long hard beak out from this S-form, and strains the whole, but at the same time it is strained downward, its wings pressed tightly against its body, its thin legs searching for a firm point beneath the water’s surface; it fixes its gaze on the flowing surface of the water, the surface, yes, while it sees, crystal-clear, what lies beneath this surface, down below in the refractions of light, however rapidly it may arrive, if it does arrive, if it ends up there, if a fish, a frog, a beetle, a tiny reptile arrives with the water that gurgles as the flow is broken and foams up again, with one single precise and quick movement, the bird shall strike with its beak, and lift something up, it’s not even possible to see what it is, everything happens with such lightning speed, it’s not possible to see, only to know that it is a fish — an amago, an ayu, a huna, a kamotsuka, a mugitsuku or an unagi or something else — and that is why it stood there, almost in the middle of the Kamo River, in the shallow water; and there it stands, in one time, immeasurable in its passing, and yet beyond all doubt extant, one time proceeding neither forward nor backward, but just swirling and moving nowhere, like an inconceivably complex net, cast out into time; and this motionlessness, despite all its strength, must be born and sustained, and it would only be fitting to grasp this simultaneously, but it is precisely that, this simultaneous grasping, that cannot be realized, so it remains unsaid, and even the entirety of the words that want to describe it do not appear, not even the separate words; yet still the bird must lean upon one single moment all at once, and in doing so, must obstruct all movement: all alone, within its own self, in the frenzy of events, in the exact center of an absolute, swarming, teeming world, it must remain there in this cast-out moment, so that this moment as it were closes down upon it, and then the moment is closed, so that the bird may bring its snow-white body to a dead halt in the exact center of this furious movement, so that it may impress its own motionlessness against the dreadful forces breaking over it from all directions, because what comes only much later is that once again it will take part in this furious motion, in the total frenzy of everything, and it too will move, in a lightning-quick strike, together with everything else; for now, however, it remains within this enclosing moment, at the beginning of the hunt.

(…)