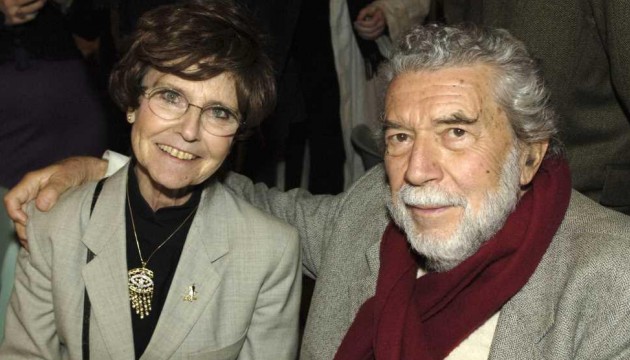

The virile looks, however, were deceptive, as his wife Catherine discovered. She was the daughter of Armenians from Iran; they met in 1951 in the Gare de Lyon, as they were both boarding a train to Istanbul. He was instantly taken by her. Barely out of her teens, not quite five feet tall and only forty kilos, Catherine Rstakian ‘looked so young then that everyone thought she was still a child’. She inspired in him (as he later wrote) ‘desperate feelings of paternal love – incestuous, needless to say’. The relationship began immediately, but with one condition, imposed by Catherine: there could be no penetration, since she had undergone a painful clandestine abortion the year before and didn’t want to risk another. Six years later, on a boat from Zadar to Dubrovnik, she changed her mind, only to learn that her fiancé was impotent. He had other things in mind for his ‘petite fille’, as he called her. ‘His fantasies turned obsessively around sadistic domination of (very) young women, by default little girls,’ she wrote in her memoir of their life together, Alain. He gave her ‘drawings of little girls, bloodied’. (‘Reassure yourself, he never transgressed the limits of the law,’ she adds.) Shortly after they were married in 1957, they drew up a contract in five pages, outlining the ‘special rights of the husband over his young wife, during private séances’, where she would submit to torture, whipping and other humiliations. If she performed her duties with ‘kindness and effort’, she would be paid in cash, which she could use for ‘expensive holidays, private purchases, or lavish generosity on behalf of third parties’.

Catherine Robbe-Grillet never signed the contract, which ‘clashed with my erotic imagination’: ‘A Master imposed himself, he didn’t negotiate.’ Writing under the male pseudonym Jean de Berg, she had explored her erotic imagination in an S&M novel,L’Image, published in 1956 by Minuit. He respected her wishes, and never asked for an explanation. When they moved into the Château du Mesnil-au-Grain, a 17th-century mansion in Normandy, it was Catherine, not Alain, who became the house dominatrix – France’s most legendary practitioner – as if she were ‘substituting myself for Alain’. He was remarkably solicitous of her needs, and she of his. He welcomed her lover, Vincent, so long as Vincent agreed to be his disciple (there could only be one Master in the house). She also shared her mistresses with him, and dressed up as Lolita when they had dinner with Nabokov. She was ‘content, even proud’, when Alain fell for Catherine Jourdain, a stunning blonde who seduced him on the beach in Djerba, where he was directing her in his 1969 film L’Eden et après; she read every letter he wrote to Jourdain. The affair appears to have been the closest thing to a conventional heterosexual relationship he had, but he was overwhelmed by her ‘voraciousness’ in bed, and she failed to be ‘the docile slave he dreamed of’. When the affair ended, Robbe-Grillet lost interest in sex. He felt burdened when Catherine offered him a close friend of hers as a birthday gift in 1975; the next year he announced his retirement from ‘all erotic activity between two people or with several’. From then on, she says, he ‘isolated himself in an ivory tower populated with prepubescent fantasies, in the pursuit, in his “retirement”, of the waking dreams in his Roman sentimental – reveries of a solitary sadist.’