Of the qualities that set Antrim apart from the group of writers he’s often casually lumped in with or excluded from — the Eugenides-Franzen-Lethem-Means-Saunders-Wallace cluster of cerebral, white-male, Northern fiction makers born around 1960 — it may be this predilection for characters “not necessarily redeemed” that offers the neatest distinction. It’s not that those other writers don’t ever do evil characters or antiheroes or that they all write tidy, hopeful plots. It’s not even that Antrim’s characters are beyond the pale in their badness, in a Cormac McCarthy manner — they aren’t psychopathic (except insofar as being human may involve being a little bit psychopathic). It’s more the case that Antrim’s fictional universe is different. It doesn’t bend toward justice, not even the kind that knows there is none but sort of hopes art can provide absolution. His universe bends — it is definitely bent — but always toward greater absurdity (in both funny and frightening guises).

Some critics have lamented over the years that his characters don’t really “change,” but they do; it’s just that they devolve, they go mad. Mr. Robinson, man and book, certainly does, in a closing passage that is both unprintable by this magazine and unwritable by any other novelist I’ve heard of, except maybe the Mississippi writer Barry Hannah in his early-1980s “Ray” period. That echo calls to mind another thing dividing Antrim from his better-known peers, that he doesn’t really come from the North, despite having made his whole career there, living in Brooklyn in a small apartment he calls “a good place to be for now for 22 years,” where he reportedly gives unforgettable dinner parties (great cooking, great stereo) throughout which everyone sits on the floor. He works in a spartan room with a plain, black desk and shelves of books, papers on the wall and a two-volume O.E.D. (the pretty one, with the little drawer for the magnifying glass).

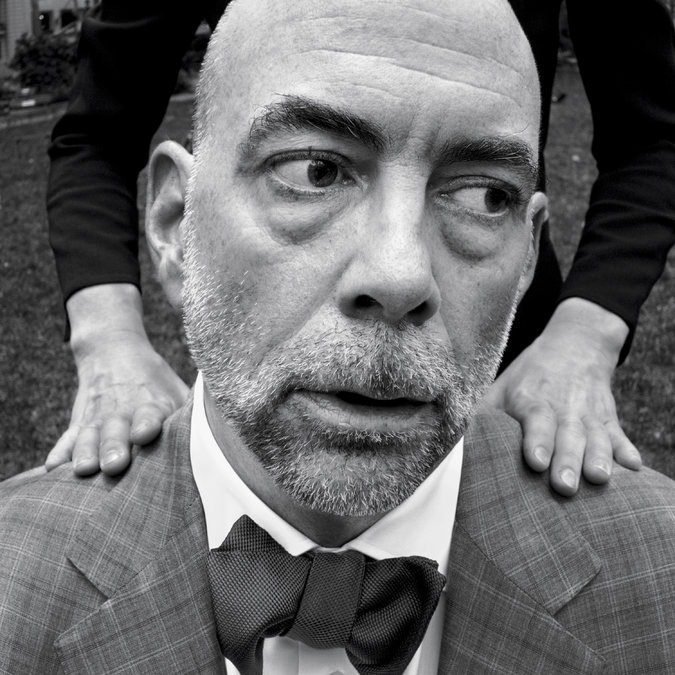

John Jeremiah Sullivan on Donald Antrim

A profile in the New York Times magazine