1.

Fetus

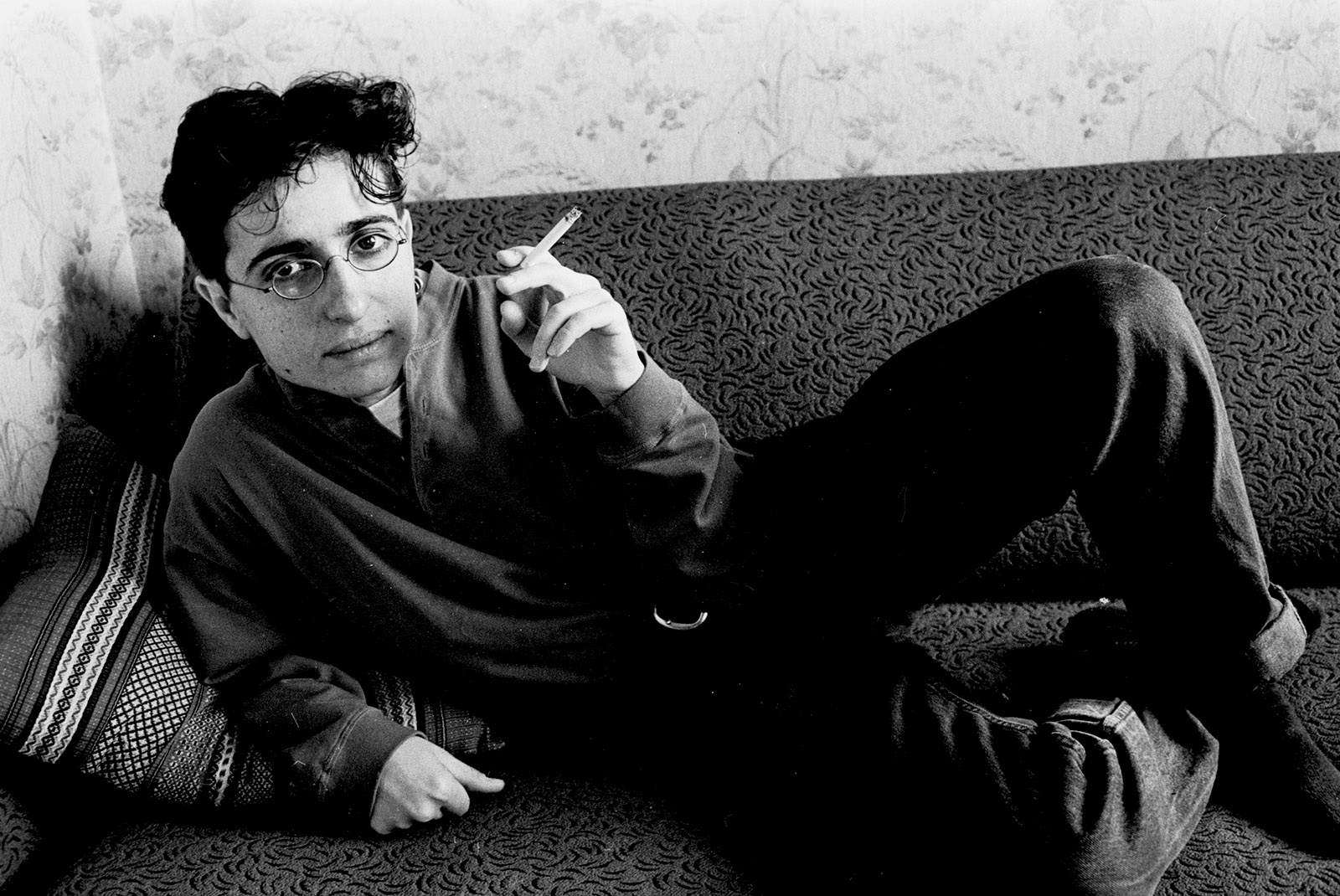

The topic of my talk was determined by today’s date. Thirty-nine years ago my parents took a package of documents to an office in Moscow. This was our application for an exit visa to leave the Soviet Union. More than two years would pass before the visa was granted, but from that day on I have felt a sense of precariousness wherever I have been, along with a sense of opportunity. They are a pair.

I have emigrated again as an adult. I was even named a “great immigrant” in 2016, which I took to be an affirmation of my skill, attained through practice—though this was hardly what the honor was meant to convey. I have also raised kids of my own. If anything, with every new step I have taken, I have marveled more at the courage it would have required for my parents to step into the abyss. I remember seeing them in the kitchen, poring over a copy of an atlas of the world. For them, America was an outline on a page, a web of thin purplish lines. They’d read a few American books, had seen a handful of Hollywood movies. A friend was fond of asking them, jokingly, whether they could really be sure that the West even existed.

Truthfully, they couldn’t know. They did know that if they left the Soviet Union, they would never be able to return (like many things we accept as rare certainties, this one turned out to be wrong). They would have to make a home elsewhere. I think that worked for them: as Jews, they never felt at home in the Soviet Union—and when home is not where you are born, nothing is predetermined. Anything can be. So my parents always maintained that they viewed their leap into the unknown as an adventure.

I wasn’t so sure. After all, no one had asked me.

2.

Vulnerable

As a thirteen-year-old, I found myself in a clearing in a wood outside of Moscow, at a secret—one might say underground, though it was out in the open—gathering of Jewish cultural activists. People went up in front of the crowd, one, two, or several at a time, with guitars and without, and sang from a limited repertoire of Hebrew and Yiddish songs. That is, they sang the same three or four songs over and over. The tunes scraped something inside of me, making an organ I didn’t know I had—located just above the breastbone—tingle with a sense of belonging. I was surrounded by strangers, sitting, as we were, on logs laid across the grass, and I remember their faces to this day. I looked at them and thought, This is who I am. The “this” in this was “Jewish.” From my perch thirty-seven years later, I’d add “in a secular cultural community” and “in the Soviet Union,” but back then space was too small to require elaboration. Everything about it seemed self-evident—once I knew what I was, I would just be it. In fact, the people in front of me, singing those songs, were trying to figure out how to be Jewish in a country that had erased Jewishness. Now I’d like to think that it was watching people learning to inhabit an identity that made me tingle.

Some months later, we left the Soviet Union.

In autobiographical books written by exiles, the moment of emigration is often addressed in the first few pages—regardless of where it fell in a writer’s life. I went to Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory to look for the relevant quote in its familiar place. This took a while because the phrase was actually on page 250 out of 310. Here it is: “The break in my own destiny affords me in retrospect a syncopal kick that I would not have missed for worlds.”

This is an often-quoted phrase in a book full of quotable sentences. The cultural critic and my late friend Svetlana Boym analyzed Nabokov’s application of the word “syncope,” which has three distinct uses: in linguistics it’s the shortening of a word by omission of a sound or syllable from its middle; in music it is a change of rhythm and shift of accent when a normally weak beat is stressed; and in medicine it is a brief loss of consciousness. “Syncope,” wrote Svetlana, “is the opposite of symbol and synthesis.”

Suketu Mehta, in his Maximum City, wrote:

Each person’s life is dominated by a central event, which shapes and distorts everything that comes after it and, in retrospect, everything that came before. For me, it was going to live in America at the age of fourteen. It’s a difficult age at which to change countries. You haven’t quite finished growing up where you were and you’re never well in your skin in the one you’re moving to.

Mehta didn’t let me down: this assertion appears in the very first pages of his magnificent book; also, he moved to America at the same age that I did. And while I think he might be wrong about everyone, I am certain he is right about émigrés: the break colors everything that came before and after.

Svetlana Boym had a private theory: an émigré’s life continues in the land left behind. It’s a parallel story. In an unpublished piece, she tried to imagine the parallel lives her Soviet/Russian/Jewish left-behind self was leading. Toward the end of her life, this retracing and reimagining became something of an obsession. She also had a theory about me: that I had gone back to reclaim a life that had been interrupted. In any case, there are many stories to be told about a single life.

(…)