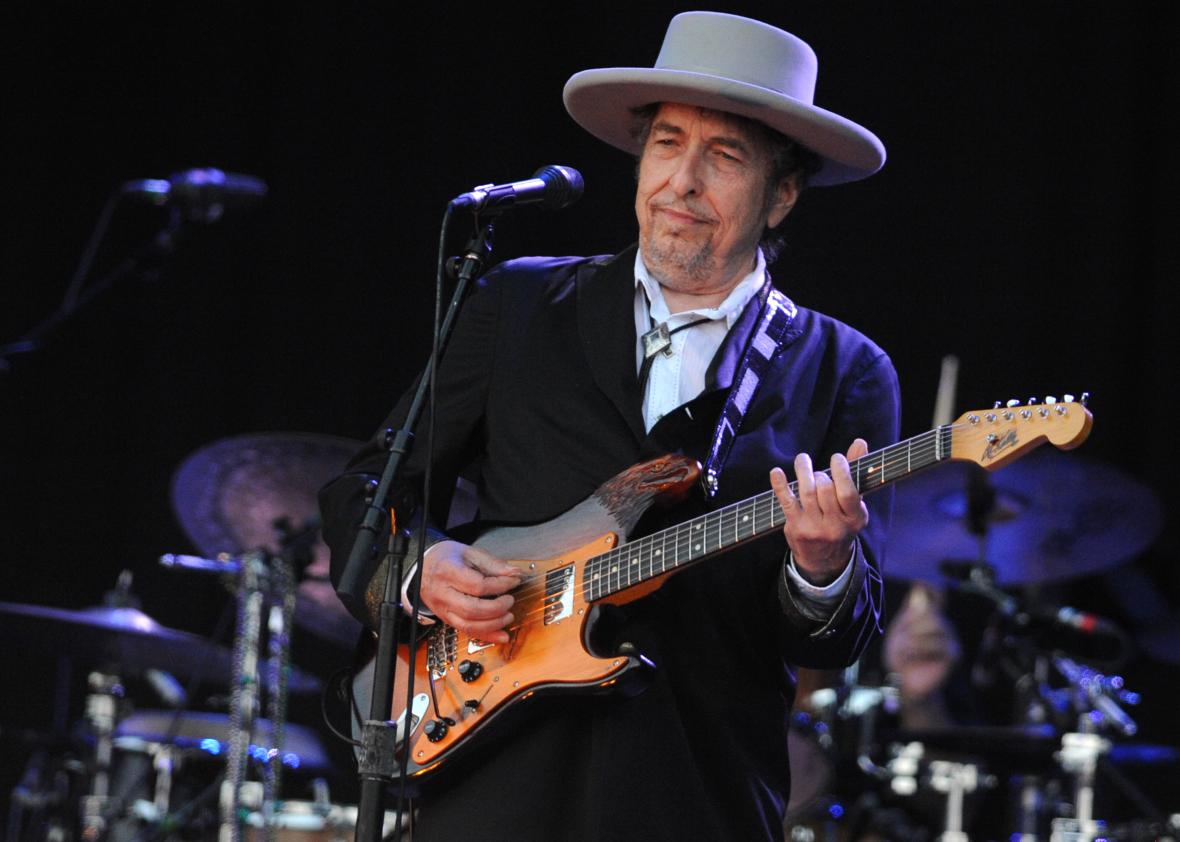

Sam Adams reviews Bob Dylan’s long-awaited Nobel Lecture for Slate.

Bob Dylan’s reluctance to even acknowledge he’d won the Nobel Prize for Literature, let alone show up to accept it in person, produced plenty of accidental comedy—to say nothing of a pronounced debate over whether songwriting could be considered a branch of literature. But his acceptance speech, which was delivered by the U.S. Ambassador to Sweden, was charming, and his Nobel Lecture, released in both print and audio form, is thoroughly engrossing.

Not surprisingly, Dylan’s Nobel Lecture is largely concerned with the relationship between literature and music, tracing, in what he admits is “a roundabout way,” a path through the songs and the novels that made the deepest impression on him. Dylan writes (and talks) about internalizing the vernacular of the folk and blues music that first inspired him:

You know what it’s all about. Takin’ the pistol out and puttin’ it back in your pocket. Whippin’ your way through traffic, talkin’ in the dark. You know that Stagger Lee was a bad man and that Frankie was a good girl. You know that Washington is a bourgeois town and you’ve heard the deep-pitched voice of John the Revelator and you saw the Titanic sink in a boggy creek. And you’re pals with the wild Irish rover and the wild colonial boy. You heard the muffled drums and the fifes that played lowly. You’ve seen the lusty Lord Donald stick a knife in his wife, and a lot of your comrades have been wrapped in white linen.

And he goes on to pay tribute to three of his favorite written works: Moby Dick, All Quiet on the Western Front, and The Odyssey. A great storyteller himself, he approaches Erich Maria Remarque’s World War I novel not as a critic or an analyst, but by slipping into the story and taking his place among his characters:

All that culture from a thousand years ago, that philosophy, that wisdom—Plato, Aristotle, Socrates—what happened to it? It should have prevented this. Your thoughts turn homeward. And once again you’re a schoolboy walking through the tall poplar trees. It’s a pleasant memory. More bombs dropping on you from blimps. You got to get it together now. You can’t even look at anybody for fear of some miscalculable thing that might happen. The common grave. There are no other possibilities.

(…)