CAMILLA’S GPS

[Camilla]

I had to go to Belgrade to give a couple of lectures, and Charles was unable to travel with me. I am a literary figure, but might have preferred to be an architect. I have a strong sense of space, I am touching my heart at this very moment. My hotel was red on the inside, Twin Peaks red; the receptionist was a legal practitioner. His life had not turned out as he had imagined. Unlike mine, he commented, referring to my visit to the institute as evidence. Though his current position, working as a receptionist for his younger brother – this was his brother’s hotel – did give him the opportunity to put his law degree to use on occasion. For instance when he had to communicate with and show around the supervisory health authorities, ‘because it demands an understanding of the law’. I wondered what it might be comparable to. Perhaps, for example, if a qualified house painter only used his qualification to buy paint for his own house, no, consider the opposite instead, how when her daughter lay dying in hospital, the author Joan Didion purchased surgical clothing and walked around the hospital ward wearing it, all the while offering sound advice to the doctors, until finally they told her that if she did not stop interfering with their treatment, they would have nothing more to do with her case, she would have to take over herself. That would be equivalent to a person, while a painter is working on their home, wearing white paint-stained clothes and standing on a ladder next to him. Welcome to my labyrinth.

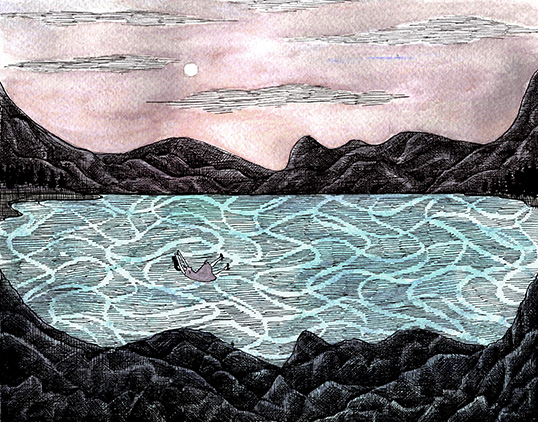

I had no desire to commit my usual blunder of isolating myself in the hotel room. At one time I enjoyed staying in hotels; staying in a room that was not mine and which I had no responsibility for, where I could quickly make my peace with any possible aesthetic qualms, and where unseen hands swept away the dust. Now I regard them as waiting rooms where it is impossible to sleep, all night long the unfamiliar objects change shape every time I blink; everything solid becomes fluid. During the day I am lightheaded and dizzy, it’s like I’m breathing thin air. My feet are heavy. I drag myself along. The minibar. No, no alcohol. Chocolate. Salted nuts. Lonely, a veritable waste of my life, munching in bed, albeit in safety. And exempt from having to find my way home-out-and-home-again. I mean: find my way around the city and attempt to find my hotel again. My sense of direction is terrible. Non-existent. Better to stay home. (Of course I did not neglect my lectures, that was the entire reason I had come, but I allowed myself to be picked up and dropped off so as not to disappear somewhere in between the two destinations, I’m talking about the rest of the time, my spare time.) But as Eliot has taught us:

We shall not cease from exploration

and the end of all our exploring

will be to arrive where we started

and know the place for the first time.

(Which does sound reassuring: as though you can be confident of returning home, automatically, so to speak.)

As a compromise, I spent quite a lot of time in the reception (not out, not entirely in) hovering on a barstool, I drank one espresso after the other. It was a small hotel, with only six rooms. And at one point I was the only guest. The staff, on the other hand – if anything they were overrepresented. I have no idea how many thin,dark chambermaids in red dresses walked aimlessly around, blending in with the walls. They weren’t prostitutes, were they? If that were the case, they might just as well have been leaning against the sunset in a deserted landscape. Nevertheless when breakfast was served in the basement, all six tables were laid. To keep up the illusion. It was called Hotel City Code, a name I was not quite sure how to interpret. Was this hotel the code to the city? When I said the name, code quickly became coat.

Before leaving, I had decided to spend every waking hour exploring the city. I wanted to be a tourist. I wanted to get to know Belgrade. And then I lost my courage. The reception, as mentioned, was my compromise.

But the receptionist talked incessantly. In a rather mumbling and unintelligible English that meant I had to strain every nerve to understand him. He had plenty of time for his only guest. As soon as I stepped out of my room, he moved towards me as though carried by a gust of wind. He was dark, slender, nimble, indefatigable, with surprisingly kind eyes hidden behind his glasses, but he kept going on and on until my mouth went dry, the room blurred and I nearly fainted. I knew the names of his siblings, I knew his cholesterol level and I knew his doctor’s instructions: ‘fifty grams of almonds, four squares of dark chocolate and a glass of red wine every day,’ he said, his small friendly face beaming, ‘and obviously eat plenty of fruit and vegetables and walk at least three kilometres.’ He bent forward and drew a curve in the air to indicate the progress of his blood pressure. I also knew that his grandfather had written an account of his experiences in World War Two, but unfortunately the manuscript had gone missing. I knew more or less what it contained. And I was starting to get the ideathat it was hidden in a barn somewhere in Croatia. I was also starting to suspect that he was encouraging me to go in search of it. He considered me to be an unusually kind person – with a lot of spare time. Ear, vagina, a mirror that makes you look twice as big; you little devil, I suddenly thought, not a chance in hell. And with that I grabbed my coat and left the reception with barely a nod. I had chosen a good time to leave. He had just stated that no matter how much money society poured into the Roma community, all they did was spend it on beer and cigarettes, and on chocolate for their many children. That was what drove me out into the world. Though I was afraid of encountering a Roma who behaved like the one I met in St Petersburg. I had given her what corresponds to a hundred kroner, and in gratitude she lay down in the middle of the street and started to kiss my shoe. ‘No, no,’ I said, ‘please get up.’ ‘Not until you give me another hundred,’ she said, and only then did she release my shoe, allowing me to continue walking towards the Spilled Blood Church, the one with the candy-coloured cupolas, which even up close did not look real.

As soon as I walked out the door, a sense of loss swept over me. With absolutely no desire to do so, I took my first steps in Belgrade. Like I was learning to walk. I knew nobody, nobody knew me. I was nobody. I did not understand the language. I understood nothing. I might as well have stopped looking where I was going, because when it came down to finding my way back, maybe I would have a vague recollection of what met my gaze, but I would not be able to remember where on my journey it had occurred. The order of the elements is not arbitrary when it comes to finding your way. Instead of trying to find my way back to the hotel later,I should have checked out and taken my luggage with me. Then, exhausted from exploring and lugging everything about, when I could manage no more, I could have dragged myself to some new, unknown hotel – and then when I absolutely had to, I could set off again. I am not that helpless. I had the address of the hotel in my pocket, and when I grew tired of walking, I hailed a taxi and rode back. An unfortunate experience in my youth had taught me to always carry the address of the hotel or guest house on my person. Greece, half a lifetime ago. Me, young, wearing a gauze Iphigenia dress, light as a feather, so white that I had had to cover my nipples with toothpaste. It was before the time of strapless bras. In any case, I had been out dancing, night-time, the flowers falling from the flowering trees. Alma, my faithless friend, continued to dance with her Greek. I could not find our pension. The longer I searched, the smaller I became. A man had been observing me for some time. In the end he cut across the street and kindly asked me what I was looking for. He had a hard time believing that I could not so much as remember the name of the pension. That which you do not understand, you simply have to accept. So at the first hotel we came across he rented a room for me and promised to return the next morning to help me. He left. He had a moustache, but he was not without some charm. Had he been less chivalrous, it might have led to a slightly lengthier encounter. The next morning he returned, paid the bill, swung onto the saddle of his moped, and with me behind him, headed for the local office of the Tourist Police. There they had a copy of my passport, which the owner of the pension had dutifully submitted upon check-in – with the name and address of my temporary residence attached! Such efficiency, and in Greece, at that. Back at the pension, I found my beloved friend Alma wringing her hands, half-dead from dread, certain that I (my head) was lying somewhere, detached from my body, under a sprinkling of browning flowers, even though we were used to ditching each other whenever some handsome mutt crossed our path. Ah, adolescence, one long mating season, a parade of brilliant memories, an entire repository of bright young passion for tougher times – did I really have a piece of red glass (grenade-like) attached to my navel and did I really display it to my temporary chosen one in a tunnel by simply lifting my dress? Yes, you bet I did! It was me, to give one final little toot. Now I use the word ‘toot’, which is Beckett’s expression for drawing out the text as much as possible, not to tie bows, but to make curls, and earlier today, duly escorted by a lecturer from the institute, on my way back from a lecture, I came across some graffiti. Sprayed on the wall were the words:

Books, brothers, books

Not bells

The lecturer translated for me and said something about bells and Santa Claus – when he arrived in his sleigh. ‘Santa Claus, you know, on a creaking carpet of cotton wool, jingle bells jingle bells, until we all hygge our arses off. Even his beard is creaking.’ Bells probably referred to church bells. So neither church nor kitsch, no thank you. Moral graffiti. Lovely to see graffiti that encourages reading, the lecturer said. ‘Exactly,’ I answered and hoped he would offer to carry my bag. Because it was heavy. With books.

(…)