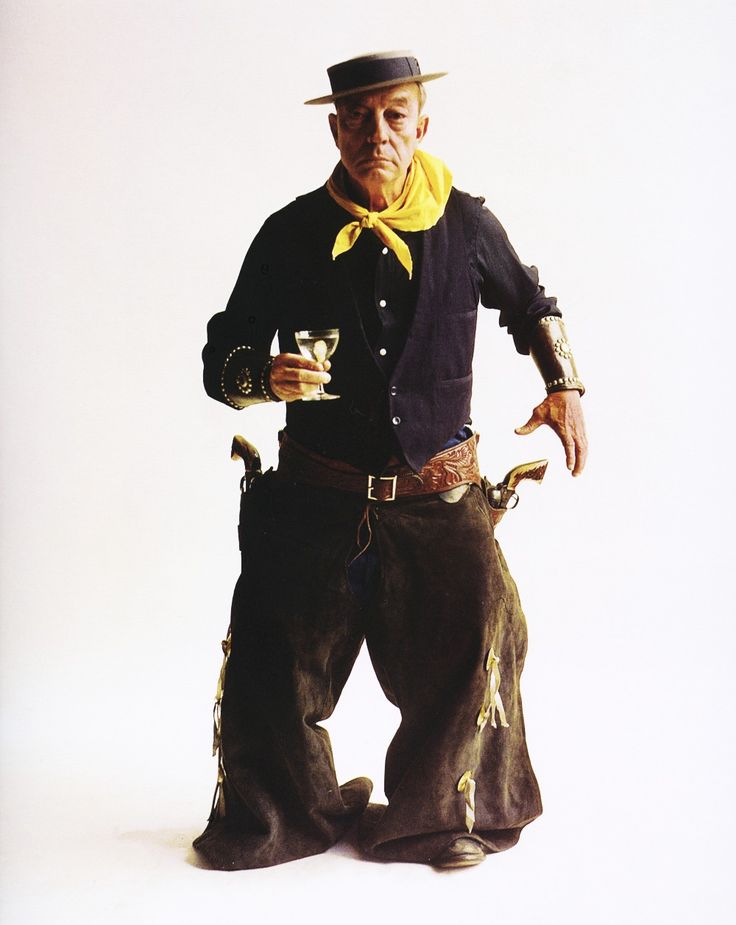

“Now, ladies and gentlemen, I have really something of great interest to the public!” The former vaudevillian Ed Wynn is providing the introductory patter to a segment in an episode of his eponymous comedy show, broadcast live in primetime on 9 December 1949. Wynn, who would later voice the Mad Hatter in Disney’s adaptation of Alice In Wonderland (1951), is a jolly host: he looks like a horned owl in a clown costume, plump and bespectacled with a rubbery excitement to his expressions that suggests he’s already half-cartoon. His speech has an avuncular warmth, tumbling with a ringmaster’s glee through his slightly pinched sinuses. The other treats on the show have included a special guest appearance from the famously deadpan actress Virginia O’Brien, nicknamed “Miss Ice Glacier,” who sang “Bird in a Gilded Cage,” and blubbery Ed’s attempt to dance a ballet overture. The curtains behind Wynn that hide the set from the audience are fuzzy, gray, and monstrously thick, looking like nothing so much as a carefully graded spectrum of various sorts of domestic dust; the studio has the acoustics of a damp attic. Wynn tells the audience that they are about to have “the great privilege in seeing for the first time, certainly on television, and alive, almost!”—an odd thing to say, don’t you think?—“one of the greatest of the great comedians of the silent moving-picture days. Mr. Buster Keaton!”

Here he is, a little man in his trademark outfit of porkpie hat and rumpled suit. He ignores all conversational prompts, playing dumb and nodding a little as if out of beat with the situation, mid-daydream. “The American public would like to hear you say something. Would you say something? Go ahead,” Wynn cajoles him, “speak!” And upon these ventriloquist’s orders, Buster commences a routine that looks like a ludic premonition of the anguished choreographies found in Samuel Beckett’s plays. (Shortly before his death, he would appear as the solitary figure in Beckett’s metaphysically queasy 1965 short, Film).1 Carefully, the voice must be readied—the whole body is involved. He shrugs his shoulders a few times, bends his knees to ensure that he’s suitably limber, then performs some exaggerated respirations that make his chest swell and deflate like a ragged bellows. There’s a mysterious procedure of cheek massage and jaw agitation in which he looks like a gargoyle attempting to reverse the effects of amphetamines. He spritzes something into his mouth, the host looks quizzically on, and what shy laughter there was in the audience has receded like a weak breeze. Then, at last, he says “Hello!” in an eager innocent’s yelp. Wynn is astonished! His owlish eyes go wide, and Buster falls, exhausted, into his arms as the audience chuckles. Television is probably more accommodating to such outbursts of staccato weirdness than any other medium, but Buster’s act is much more than just an odd trick. He isn’t out of shape: a subsequent re-enactment of “the first scene he ever did for a camera” will prove he’s freakishly limber for a fifty-four-year-old and his timing’s still pin-sharp. This impish revision of an old routine about a hatful of black molasses, with Wynn taking the role originally played by Buster’s old pal (and Hollywood outcast) Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle will exaggerate the formal habits of silent film—intertitles and melodramatic expressions—to levels of inspired lunacy. Like in all his best films, the sleepwalking smoothness of his physical antics combines with a preternatural sense of how film itself can be the subject of witty subversions and knowing mischief.

That bewildering joke, which suggests that Buster can only speak after laboriously readying his body, plays on the strange fate of silent film stars in our imagination: silence is a symptom of their magical condition. The more of them you watch, the more difficult it becomes to think of them as possessing voices at all. (Would Theda Bara be mute in public, too?) What breeds in silence is, naturally, a sort of excitable noise: heightened fascination, fantastical lore, and outlandish forms of erotic gossip, all of which conspire to hide the dumbstruck star. The uproarious arrival of sound often led these delicate figures into the long and lonely twilight of their careers. The silence that reigned in the cinema twenty years before seemed unspeakably distant and, like the others, Buster had transformed into a relic, an object suitable for gawking audiences and inducing occasionally lyrical fits of nostalgic reflection. But he was able to stage a return when many had retreated into memory or private darkness. The year of his appearance on The Ed Wynn Show, Clara Bow, the actress who had slinked through the world’s erotic dreamscape for much of the 1920s, had been admitted to a mental hospital with a mistaken diagnosis of schizophrenia, then subjected to aggressive electroshock treatment. Ravaged upon release, she abandoned her family and moved into a bungalow near Los Angeles that she seldom left until her death in 1965. Buster was ruined by a slow fall into alcoholism but returned, and yet his rehabilitation and—let’s go for the hysterical mood of melodrama—resurrection conjure up more ghosts. His alcoholism was seemingly cured by a manic, spuriously medical process, and he didn’t quite vanish in the obscure years before its success. There’s plenty of intoxicating material to be found by studying Buster if you dodge the lustrous peaks of his career in favor of going deep into its gloom and supposed dead ends.

Unfurling this distended postscript without acknowledgement of the astonishing properties of Buster’s art would be unkind. A case study of his childhood might be equally rich, too. Born in 1895, which makes his age exactly synchronous with cinema itself, he was a willing participant in vaudevillian mishegoss as soon as he could walk. According to myths circulated by his father, he had survived a few twirls in the eye of a Kansas tornado when he was three. Alongside his parents, he was part of the Three Keatons, a riotous slapstick act in which his mother played saxophone and his father discoursed on child discipline while hurling Buster about the stage. His education was irregular; his father was an alcoholic. In photographs from this time, he looks like a playful wraith.

As a child, silent cinema was a ghost house I had to explore. My sense of reality was already perilously vague and the thought of these films that would allow me to watch the mischief of specters—everyone in them was, by the time of my childhood, decidedly dead—was a deep and wicked thrill. Whole days disappeared in the attempt to cast the shadow of Nosferatu on the wall as I climbed the stairs again and again. (I failed: it was very tough to get the head correct, my skull lacking the required Expressionist jags.) I remember chancing across Buster’s face in a film history book one monochrome morning and feeling the peculiar sensation that this haunted boy knew I was looking at him. Wholly at odds with the wild-eyed mania that silent film acting often promised, his presence was gentle and radiated an unmistakable sadness. He had the dreamy, lonesome look of a stray dog. His eyes would widen in moments of moonstruck goofing or genuine enchantment, then look on the edge of sleep when he was puzzled. Nobody else’s body yielded so smoothly to the sublime mindlessness that the best physical comedy requires, and he was beautiful in a way that, say, a clerical nebbish like Harold Lloyd would never match. On film, even in flashes of jackrabbit energy, he’s airily nimble and weirdly aided by the jittery accelerations and diminuendos of silent film speed that can make him seem too limber in his skittering or too light in his falls to be made of flesh and bone. At those moments he’s closer to a bewitched marionette.

In 1928, Buster was talked into giving up his own studio, where he made his finest films, and switching to the ascendant MGM. Bad contracts were signed; dark clouds began to settle in his head. His subsequent drift into alcoholism looks like a commonplace response to the baleful state of Hollywood and deep marital discord. Seven years before, Buster had married Natalie Talmadge, a delicate, fawn-like beauty of seemingly untrammelled malevolence who banished him from their bedroom once he had supplied her with the two sons (and the mansion) she required, reported him for kidnapping when he took the boys for a weekend jaunt, and refused to hear his name in her presence until she died in 1969 after years blasted on painkillers and hopelessly soaked in booze. She appears to have dreamed of transforming Buster into a bland mixture of benefactor and milquetoast, though let’s note that as the far less successful middle sister of two wildly famous actresses, Norma and Constance, she was never able to tell her own story, skewed and vituperative as it might have been. Natalie’s chief occupation was perfecting the girlish swirls of her sisters’ signatures on an endless cascade of publicity stills. In a photograph taken on their wedding day, Buster stands in between the three sisters in a spotlight of May sunshine, looking like a man about to be led to the gallows. Norma and Constance retired with the advent of the talkies. Norma was reputedly the inspiration for Lina Lamont in Singin’ in the Rain(1952), the starlet of uncommon radiance destroyed by the arrival of sound, which reveals to the world that she’s in possession of the shrill, needling voice of a Brooklyn chipmunk. The reclusive, gone-to-ruin silent movie heroine played by Gloria Swanson in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard(1950) is also an acidulous portrait of Norma. Like her sister, she suffered an unhappy fate, fleeing to Las Vegas, gorging on painkillers, seeing no one, and drinking all the time until she died there on Christmas Eve in 1957. (Much the same happened to Constance: they made a tragic trio).

As the marriage dissolved, Buster tumbled toward oblivion, too, succumbing to the song of what he called his “inner Bacchus” in order to escape domestic pressures. He became estranged from his sons, whose last names were changed so that they were suddenly Talmadge property. The pleasures of drinking had long since faded into the delirious routine of everyday alcoholism as he got drunk from sunrise until he blacked out. As he recalls in his autobiography, My Wonderful World of Slapstick (1960), “all my weekends were lost weekends.”2 He left the mansion and drifted around Hollywood in a land yacht, “a fancy house on wheels that had twin motors in the chassis of a Fifth Avenue bus, contained two drawing rooms, a galley, an observation deck and slept eight persons.” By way of melancholy endorsement, he notes, “I had as much fun with my land yacht as a man can whose purpose is to forget his whole private world has fallen apart.” In a drunken blur one Monday afternoon, he staggered down to the MGM lot and befriended an extra—“I could not say today whether she was a blonde, brunette or a redhead”—took her home, and let her have her pick of the contents of Natalie’s enormous wardrobe, heaping up piles of cocktail dresses, fur coats, gowns, and sparkling shoes. He appeared in What? No Beer! (1933), a dismal but hugely successful talkie with the antic Jimmy Durante in which this mismatched double act accidentally become beer barons as Prohibition’s on the wane. Buster plays a taxidermist and suitably moves with the shambling gait of a bear half-stuffed with wool. When shooting was over one night, he tried to drink himself into unconsciousness but failed and came reeling into the studio the next morning, only to promptly pass out.

When he awoke, he found a letter from the studio bosses telling him he was fired. Buster had become a drunk at a time when alcohol was a source of immense moral panic. (William Burroughs’s grandmother had the motto, “I’d rather a son o’ mine came home dead than drunk!”) Grimmest of all, he had fallen for whiskey, which, as he said later, was popularly regarded as “pure evil, apparently being distilled in hell itself.”

Throughout the early 1930s, the backdrops shuffled like a collection of old postcards as Buster appeared in cheap slapstick short films shot in Mexico, France, and England. He read the “idiot cards” that rendered lines in foreign languages into phonetic English, repeating his dialogue over and over again for different territories to save on the expense of dubbing. Drinking was a useless form of self-sabotage—even knockout drunk, he was still able to perform his stunts.

(…)