Corina Copp—How did this museum show come about? You recently said, “I’m not in the closet, but a lot of my artwork is.” How did your artwork gradually make its way out of the closet, so to speak? The title of the show, Evidentiary Bodies, could connect to an evidentiary hearing, like in the court system when—

Barbara Hammer—everything is brought forth.

CC Did you title it this way partly because you think of your work as evidence of a life lived?

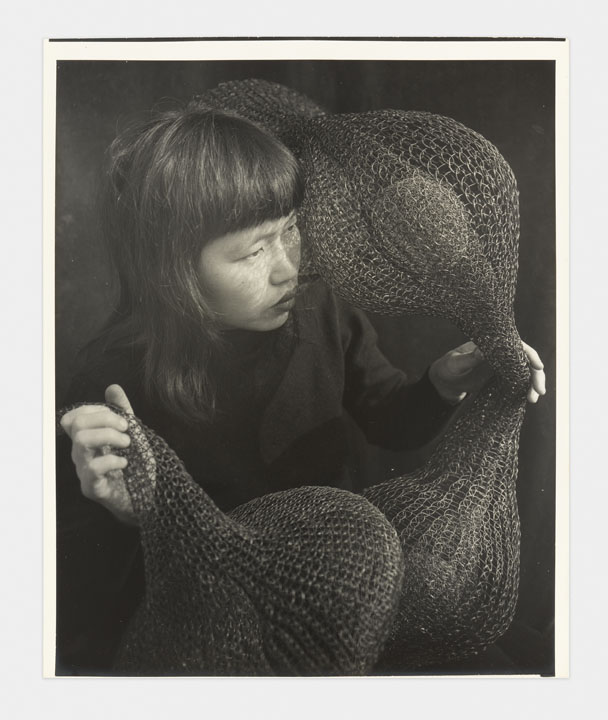

BH I did. I’ve had lots of retrospectives but none that represented all of my output. They’ve always just shown moving-image work. So this broader survey enticed me right away—especially as an excuse to open up those boxes, and to get some eyes other than my own on the work. I was allowed to choose the curators, who became my close friends. And during this time the museum had a change of direction toward greater diversity, toward lesbians of color, queer people with disabilities, and so on. It was the right team for a survey several years in the making.

CC How was the work selected? Was any of it from the journal archives? I know they were recently sent to the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale.

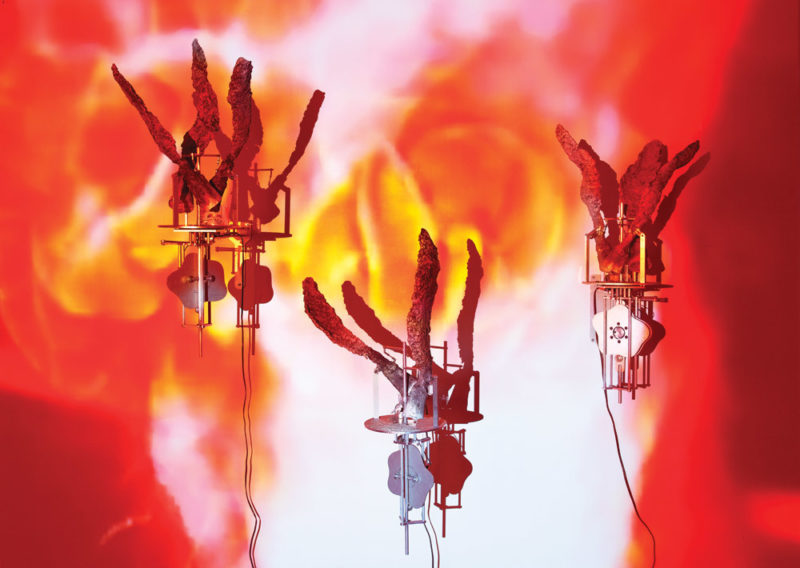

BH A lot of what was on display is from Yale. There were also drawings similar to those in the journals that mostly came from my studio. When I started out, I didn’t make things thinking of galleries at all. I self-identified as a filmmaker but worked in all these other disciplines. I’d lay boards out in the backyard and spray-paint them blue, then arrange them on the grass in a certain way, with some wires going across, to be photographed. It was perhaps conceptual sculpture, similar to Cady Noland’s work. But my discipline was filmmaking, and that became the main course because it could include painting—I paint on a lot of film and reshoot it—plus performance and installation too. Later, I brought in research. For example, it was a great delight finding out about Elizabeth Bishop for my most recent feature essay film, Welcome to This House (2015). I read every book about her and dipped into her archive to investigate aspects of her life—like the homes she lived in and how they influenced her poetry. I visited Great Village, Nova Scotia; Key West, Florida; Ouro Preto and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; and Cambridge and Boston, Massachusetts.

CC You’re a big Elizabeth Bishop fan?

BH Well, my first master’s was in literature, and poetry was my love. I even wrote poetry for a while when I was young. But back to the show: the curators had free rein.

CC Whether it’s including loose ephemera in the new monograph—like a collectible trading card and a sticker by Vanessa Haroutunian that reads Barbara Hammer Says Yes!—or seeking-out audience members one by one after a screening, or building into your films direct conversations with strangers, lovers, and new friends, your affection for participation, or—I’d like a better word for it—encounter, or optimistic relation, is evident. But you can’t always be there engaging with people. The gallery work has a delayed sociality, whereas the films feel more immediate. Is it important for you to talk with the people who see these works in a way somehow similar to previous audience engagements at your films? I imagine you’re getting feedback from women about their experiences.

BH And men too. I just got an email from the artist Brent Green, who saw Truant, my recent show of photography from the 1970s. He wrote: “I knew you were a badass, but you were a badass way back then.” (laughter)

But you’re onto something here. I’ve sat in the museum a few afternoons, watching people look at my work, overhearing some of their comments. It didn’t give me the thrill of interaction that live performance, live film projection, and live audience snoring, grunting, or laughing in their seats does. They’re perceiving the past; and I’m glad there’s a past to observe in the art and artifacts, but it’s an intellectual pleasure knowing that. What grips my being is the dialogue, the confrontation, the smiles of direct engagement. That’s special—the emotional pleasure of person-to-person(s) gaze, touch, and talk. Did I say exchange? Do I have to say relational?

There was something different happening during the opening of Truant. It was like looking at vulnerability without design, camouflage, and pretense, even without that sacred art cow: irony. Innocence, joy, authenticity, agency, playfulness, and community encounter speak to me even now from those past records. The spontaneous—or so it seemed—feminist, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender revolution in the Bay Area following immediately after and often in conjunction with the vibrant, hopeful turmoil of the hippies and Black Panther movement was the zeitgeist. You couldn’t ignore it as a sentient being. You were a lucky sentient being to be alive and aware of this strength-in-vulnerability expressed by so many courageous beings damned sure doing their best to make a change in a rigid social structure.

When I look at those photographs, I still feel our energy and desire, and that leaves me in the open, wondering state of tenderness. Vulnerability is not a weakness in a computer system, a personal flaw in another, or an exposure to be covered over or protected. Our vulnerability to one another and to ourselves is our strength.

(…)