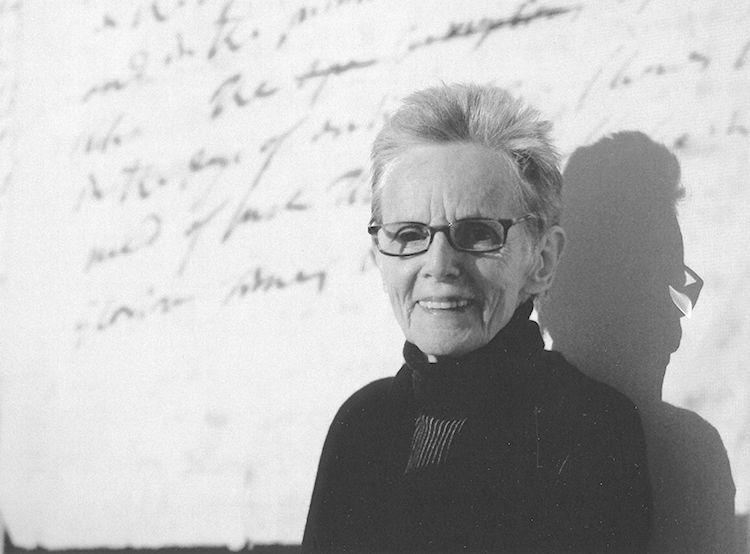

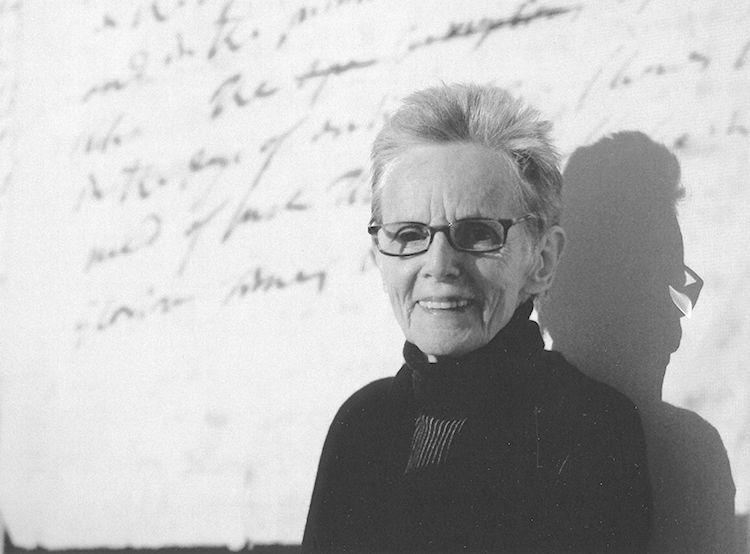

Emily LaBarge on Susan Howe’s Depths for Bookforum:

“Only art works are capable of transmitting chthonic echo-signals,” writes Susan Howe in the foreword to her new collection, Debths, inspired in part by the Whitney’s 2011 retrospective of American artist Paul Thek.

I have always been interested in folktales, magic, lost languages, riddles, coincidence, and missed connections. What struck me most was the way [Thek’s] later works, often painted swatches of color spread across sheets of newspaper with single words, phrases, or letters scribbled over the already doubled surface, transformed these so-called “art objects,” into the epiphanies, riddles, spells and magical thinking I experienced one afternoon in the old Whitney Marcel Breuer building.

Howe has long been interested in distilling signs and symbols, whether “art objects” or words themselves, into something more revelatory. Considering riddles, lost languages, doubled surfaces, spells, magical thinking, and other elusive forms of expression, Howe sounds the depths. She detects the chthonic—meaning “underworld”—echo signals reflecting off all that dwells beneath the surface. Howe’s work considers the ways in which deep histories collide and overlap in fathomless strata, replete with gaps and fissures where obscure knowledge may be found.

The poet has referred to herself as a “library cormorant,” a phrase borrowed from the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who wrote, “I am deep in all out of the way books, whether of the monkish times, or of the puritanical era.”For Howe, who studied Fine Art at the Boston Museum School and arrived at literature from a non-academic background, libraries and their special collections are “Lethean tributaries of lost sentiments and found philosophies” in which one can feel “the telepathic solicitation of innumerable phantoms.” Lethean is a word of the chthonic family—Greek in origin and related to the afterlife—a reference to the river Lethe in Hades, whose water would cause dead souls to forget their lives on earth. Lethean forgetfulness is oblivion—the complete erasure of an entire world.

Howe’s use of language is particular and idiosyncratic. It snakes and branches through shared etymologies and thematic resemblances. In this Lethean quotation run two strands that are evident across the poet’s oeuvre: the material and the metaphysical. On the one hand, the notion that there are real, material histories that have been overlooked and overwritten, and that, through a sustained encounter with a primary source, one can unlock these narratives and find evidence of a lost world. On the other hand, the sense that there is another place entirely—felt but unseen and unheard—that reading and writing usher us toward. There, we might find another language entirely, one that relies on alternative approaches to making meaning and associations, and is attuned to the logic of the imaginary that eddies beneath the surface of the world we think we know. In Howe’s work, there is the sense that a written document is also an image whose inscriptions can be interpreted beyond the literal sphere. To read and to write is to make and unmake a riddle—to conjure, to speak in tongues.

Howe is a poet of the archives. She perceives and investigates the stutters and absences in the historical record, particularly in the literary artifacts we have deemed worthy to attend to and preserve. “When we move through the positivism of literary canons and master narratives,” she writes in The Birth-mark, her astonishing and incisive 1993 study of early American literature, “we consign ourselves to the legitimation of power, chains of inertia, an apparatus of capture.” In the history of literature, she asks, who and what remains unquantified? What experiences and uses of language have been deemed inexpressible or invalid? Is there another kind of sense, a different mode of narrative, buried within seemingly innocuous documents?

If you are a woman, archives hold perpetual ironies. Because the gaps and silences are where you find yourself. . . . “The stutter is the plot.” It’s the stutter in American literature that interests me. I hear the stutter as a sounding of uncertainty. What is silenced or not quite silenced. All the broken dreams.

In Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of Archives (2014), a slim volume that traces how a series of documents linked by geographic place speak to each other and reflect interwoven histories, Howe writes of the “deep” text that emerges from beneath the surface of archival materials. The deep text could be read as the secret, esoteric meaning of a document, which can be apprehended in its language, as well as in haphazard markings across the page. The deep text could also be read as central to much of Howe’s own work and writerly methodologies. Moving deftly between literary criticism, historical analysis, essay, text collage, and poetry, Howe conjoins forms, one aspect of exegesis shifting seamlessly into the next. In each case, her method is not to weave together references and arguments, but to place them in proximity: connections are implied or left for the reader to cast; a text is not a straight line, but a web. This is a poetic method that urges the reader backward to the originary source of the text rather than forward toward a delimited meaning. In other words, Howe does not uncover what a text “means,” but instead asks: Where did it come from? What shared sources and affinities? What wild, untrammelled force?

(…)