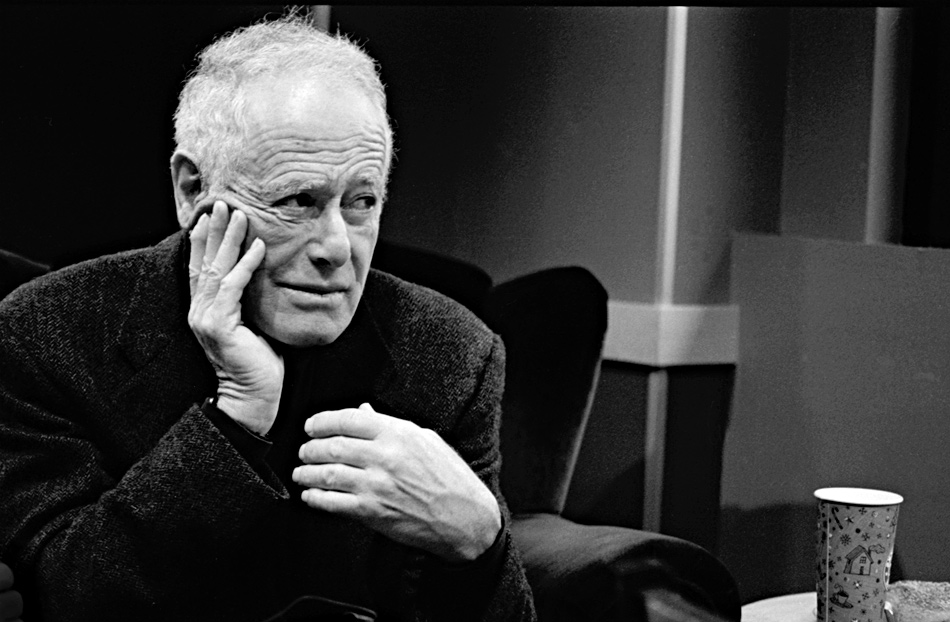

A great writer, James Salter, died aged 90 last Friday. Here’s an excerpt from his Paris Review interview from 1993, on his French literary influences:

INTERVIEWER

Do you think your sensibility is French?

SALTER

Not particularly. Ned Rorem said that it is. I like France, and I like the French, but no.

INTERVIEWER

Is Colette a figure who has meant anything to you?

SALTER

Oh, yes. I don’t remember when I first came upon her. Probably through Robert Phelps, although I must have read scraps here and there. Phelps was a great Colette scholar who published half a dozen books about her in America, including a book I think is sublime, Earthly Paradise. It’s a wonderful book. I had a copy of it that he inscribed to me. My oldest daughter died in an accident, and I buried it with her because she loved it too.

Colette is a writer one should know something about. I admire the French for their lack of sentimentality, and she, in particular, is admirable in that way. She has warmth; she is not a cold writer, but she is also not sentimental. Somebody said that one should have the same amount of sentiment in writing that God has in considering the earth. She evidences that. There’s one story of hers I’ve read at least a dozen times, “The Little Bouilloux Girl” in My Mother’s House. It’s about the most beautiful girl in the village who is so much more beautiful than any of her classmates, so much more sophisticated, and who quickly gets a job at a dressmaker’s shop in town. Everyone envies her and wants to be like her. Colette asks her mother, Can I have a dress like Nana Bouilloux? The mother says, No, you can’t have a dress. If you take the dress, you have to take everything that goes with it, which is to say an illegitimate child, and so forth—in short, the whole life of this other girl. The beautiful girl never marries because there is never anyone adequate for her. The high point of the story, which is marvelous because it is such a minor note, comes one summer when two Parisians in white suits happen to come to the village fair. They’re staying nearby in a big house, and one of them dances with her. That is the climax of the story in a way. Nothing else ever happens to her. Years later, Colette is coming back to the village. She’s thirty-eight now. Driving through town she catches sight of a woman exactly her own age crossing the street in front of her. She recognizes and describes in two or three absolutely staggering sentences the appearance of this once most beautiful girl in the school, “the little Bouilloux girl,” still good-looking though aging now, still waiting for the ravisher who never came.

INTERVIEWER

When did you get to know Robert Phelps?

SALTER

It must have been in the early 1970s. A letter arrived, a singular letter; one recognized immediately that it was from an interesting writer, the voice; and though he refrained from identifying himself, I later saw that he had hidden in the lines of the letter the titles of several of the books he had written. It was a letter of admiration, the most reliable form of initial communication and, as a consequence, we met in New York a few months later when I happened to be there. He was, I discovered, a kind of angel, and he let me know, not immediately, but over a period of time, that I might belong, if not to the highest company, at least to the broad realm of books and names—more was entirely up to me.

Phelps introduced me to the French in a serious way, to Paul Léautaud, Jean Cocteau, Marcel Jouhandeau, and others. His life in some respects was like Léautaud’s—it was simple. It was unluxurious and pure. Léautaud lived a life of obscurity and only at the very end was rescued from it by appearing on a radio program that overnight brought him to public attention—this quirky, cranky, immensely prejudiced, and educated voice of a theater critic and sometime book writer and diarist who had unmercifully viewed life in the theater for some fifty years and lived in a run-down house with dozens of cats and other animals and, in addition to all this, carried on passionate love affairs, one for years with a woman that he identified in his diaries as The Scourge. Phelps had some of that. He lived a very pure life. Books that did not measure up to his standards he simply moved out into the hall and either let people pick up or the trashman take away. He did this periodically. He went through the shelves. So on his shelves you found only the very best things. He believed in writing. Despite every evidence to the contrary in the modern world, he believed in it until the very end. Phelps died about three years ago. I said I thought of him as an angel. I now think of him as a saint.

INTERVIEWER

It seems as if André Gide was a major influence on you at one time.

SALTER

He was, but I cannot remember exactly why. I read his diaries when I first started writing in earnest, and then I read, and was very impressed by, Strait Is the Gate. I had an editor at Harper Brothers, Evan Thomas, who asked me what I was interested in, and I told him I was interested in Gide. A look of bewilderment or dismay crossed his face, as if I’d said Epictetus, and he said, Well, what book of his are you reading? I said, Strait Is the Gate. It’s simply a terrific book. Have you read it? He said, No. I could tell from his tone that it was not the sort of thing he read or that he approved of my reading. My impression of Gide, looking back, is of an unsentimental and meticulous writer. I would say my attentions were not drawn to the wrong person.

INTERVIEWER

Are there other French writers who particularly influenced you?

SALTER

I’ve read a lot of them. Among those who are probably not widely read I would say Henry de Montherlant is particularly interesting. Céline is a dazzling writer. Here we have a disturbing case. Certain savage works of his have been stricken from the list. We know his views. The French almost executed him themselves. So we are talking about a dubious personage who is now deemed, I think correctly, as one of the two great writers of the century in France. It’s a perfectly valid nomination. Even his last book, Castle to Castle is tremendous. It must have been written in the most trying circumstances imaginable. When you read something good, the idea of looking at television, going to a movie, or even reading a newspaper is not interesting to you. What you are reading is more seductive than all that. Céline has that quality.

(…)