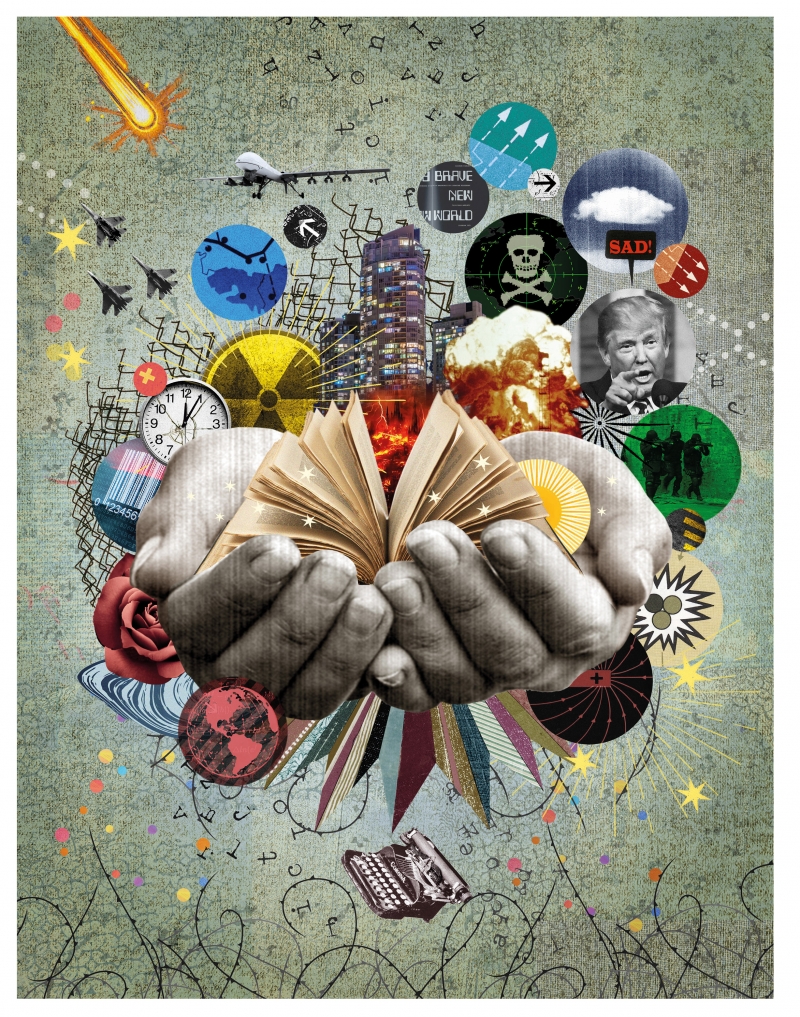

Ali Smith’s Goldsmiths Prize lecture on the importance of the novel, featured in the New Statesman:

The novel matters because though all the arts are family, related, and I tend to think at their best when they meet up with or cross over into each other, among them the novel is particularly versatile at this crossing-over in that it can borrow from and chameleon with and meet the other forms with immensely fruitful outcome. Where it crosses into the poem, and the short story – where it borrows from these forms’ essentiality, concentration and tight edit, where it borrows the short story’s indebtedness to our own mortality, and its ability to stretch form, its spatial elasticity; and where it borrows the poem’s deep-rooted ancientness of both voice and form, and borrows from both their way of allowing emphasis to work by resonance, like rings in water, as part of the shift of what we call plot – the novel blossoms into intensity.

Its structural possibility learns from the sculptural arts, where something extra-dimensional happens to the form – say you decide, like Henry James or Georges Perec, to cut a Barbara Hepworth-like hole in your novel either by leaving something unsaid, like James so often does, leaving readers with a hole at the centre of their reading, then that unsaid thing that pierces the work will also pierce the reader. Or say like Perec you cut out something physical like he does in La Disparation, in which a man called M Vowl disappears and so does one of the five vowels, the e, leaving many words unabl to b us d, writt n down, spok n by th voic of th nov l, which in turn opens a window on the absences in history, causing the haunting of the novel and its reader by things gone, removed, unseen, unsaid, unsayable.

And because the novel is, like the language that goes to make it, naturally rhythmic, it can sing anything and everything from the three-minutes-of-happiness pop song to the opera cycle, or both at once, and because every story tells a picture and every word paints a thousand of them, and because the novel’s footwork, its choreography with its partner in the dance, the reader, is why and how it moves us, there are the novels, like Angela Carter said of The Great Gatsby, that we lie back and have done to us, and there are the novels that ask us to do a lot or even just a little of the footwork. We all know about picking up a novel and hitting its first pages as if hitting a brick wall – but once you’ve committed, that’s you climbing over or knocking a door or a window through, and pretty soon you’ll be waltzing through walls, and so on.

The novel matters because and so on. By which I mean that I’ve come to believe that all the arts are about time, but that the novel in particular is about the and-so-on of things, continuance and continuity, the continuum. It’s a form, too, very interested in the workings of society, so it tells us about how we’re living, who we’re living with, and where we are in the endless social structural cycle that eventually gets called history.

But where the short story is a form whose briefness suggests our own – whose shortness signals what Katherine Mansfield (so short-lived herself, a writer who revolutionised the short form and was dead before she’d reached her mid thirties) has a character in a story called “At the Bay” declare: “The shortness of life! The shortness of life!” – the novel as a form is about the long view, the time continuum, in a way that suggests that even though the novel ends, time doesn’t, or won’t. No, the novel keeps on ticking, even if you pulverise it, like Stein, even if you bend it, like Woolf, or bend time in it, like Amis, and this makes it a comfort as a form, an ever-blooming thing, blooming out of itself, novel is a novel is a novel is a novel, which makes me think of the great Norwegian poet Henrik Wergeland, dying young and saying just before he died, kiss next year’s roses for me.

(…)