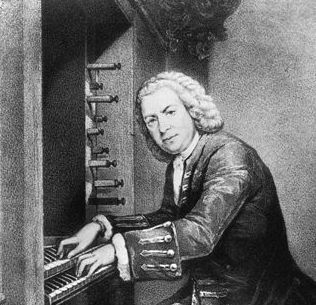

At the corner of 8th and Market in San Francisco, by a shuttered subway escalator outside a Burger King, an unusual soundtrack plays. A beige speaker, mounted atop a tall window, blasts Baroque harpsichord at deafening volumes. The music never stops. Night and day, Bach, Mozart, and Vivaldi rain down from Burger King rooftops onto empty streets.

Empty streets, however, are the target audience for this concert. The playlist has been selected to repel sidewalk listeners — specifically, the mid-Market homeless who once congregated outside the restaurant doors that served as a neighborhood hub for the indigent. Outside the BART escalator, an encampment of grocery carts, sleeping bags, and plastic tarmacs had evolved into a sidewalk shantytown attracting throngs of squatters and street denizens. “There used to be a mob that would hang out there,” remarked local resident David Allen, “and now there may be just one or two people.” When I passed the corner, the only sign of life I found was a trembling woman crouched on the pavement, head in hand, as classical harpsichord besieged her ears.

This tactic was suggested by a cryptic organization called the Central Market Community Benefit District, a nonprofit collective of neighborhood property owners whose mission statement strikes an Orwellian note: “The CMCBD makes the Central Market area a safer, more attractive, more desirable place to work, live, shop, locate a business and own property by delivering services beyond those the City of San Francisco can provide.” These supra-civic services seem to consist primarily of finding tasteful ways to displace the destitute.

The inspiration for the Burger King plan, a CMCBD official commented, came from the London Underground. In 2005, the metro system started playing orchestral soundtracks in 65 tube stations as part of a scheme to deter “anti-social” behavior, after the surprising success of a 2003 pilot program. The pilot’s remarkable results — seeing train robberies fall 33 percent, verbal assaults on staff drop 25 percent, and vandalism decrease 37 percent after just 18 months of classical music — caught the eye of the global law-enforcement community. Thus, an international phenomenon was born. Since then, weaponized classical music has spread throughout England and the world: police units across the planet now deploy the string quartet as the latest addition to their crime-fighting arsenal, recruiting Officer Johann Sebastian as the newest member of the force.

Experts trace the practice’s origins back to a drowsy 7-Eleven in British Columbia in 1985, where some clever Canadian manager played Mozart outside the store to repel parking-lot loiterers. Mozart-in-the-Parking-Lot was so successful at discouraging teenage reprobates that 7-Eleven implemented the program at over 150 stores, becoming the first company to battle vandalism with the viola. Then the idea spread to West Palm Beach, Florida, where in 2001 the police confronted a drug-ridden street corner by installing a loudspeaker booming Beethoven and Mozart. “The officers were amazed when at 10 o’clock at night there was not a soul on the corner,” remarked Detective Dena Kimberlin. Soon other police departments “started calling.” From that point, the tactic — now codified as an official maneuver in the Polite Policeman’s Handbook — exploded in popularity for both private companies and public institutions. Over the last decade, symphonic security has swept across the globe as a standard procedure from Australia to Alaska.

(…)