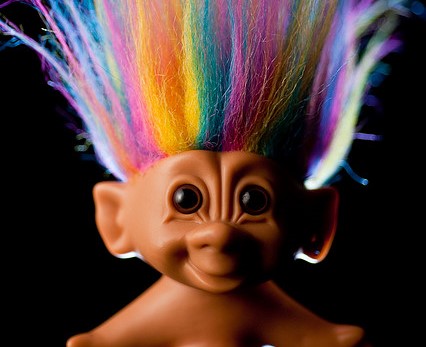

Trolls are the self-styled pranksters of the internet, a subculture of wind-up merchants who will say anything they can to provoke unwary victims, then delight in the outrage that follows. When Mitchell Henderson, a 12-year-old boy from Minnesota, killed himself in 2006, trolls descended on his MySpace page, where his friends and relatives were posting tributes. The trolls were especially taken with the fact that Henderson had lost his iPod days before his death. They posted messages implying that his suicide was a frivolous response to consumerist frustration: ‘first-world problems’. One post contained an image of the boy’s gravestone with an iPod resting against it.

What’s so funny about trolling? ‘Every joke calls for a public of its own,’ Freud said, ‘and laughing at the same jokes is evidence of far-reaching psychical conformity.’ To understand a joke is to share a culture or, more precisely, to be on the same side of an antagonism. Trolls do what they do for the ‘lulz’ (a corruption of ‘LOL’, Laughing Out Loud), a form of enjoyment that derives from someone else’s anguish. Whitney Phillips, whose research has involved years of participant-observation of trolls, describes lulz as schadenfreude with more bite. The more furious and upset the Henderson family became, the funnier the trolls found it.

In 2011, one of these ‘RIP trolls’, Sean Duffy, a 25-year-old from Reading, was jailed for posting messages online about dead teenage girls. He called Natasha MacBryde, who had killed herself aged 15, a ‘slut’; on Mothers’ Day he posted a message on the memorial page of 14-year-old Lauren Drew, who had died after an epileptic fit: ‘Help me mummy, it’s hot in hell.’ Often, trolls gang up on their targets. Phillips details the case of a Californian teenager called Chelsea King, who was raped and murdered in February 2010. Her relatives were treated as fair game, and supportive strangers who tried to intervene were themselves tracked down and hounded.

RIP trolling treats grief as an exploitable state. It isn’t that the trolls care one way or another about the person who has died. It’s that they regard caring too much about anything as a fault deserving punishment. You can see evidence of this throughout the trolling subculture, even in more innocuous instances. In one case, participants phoned video-game stores to inquire about the non-existent sequel to an outdated game. They called so persistently that the workers answering the phone would fly into a rage at the mention of the game, to the amusement of the trolls. The supreme currency of trolling is exploitability, and the supreme vice is taking anything too seriously. Grieving parents are among the easiest to exploit – their rage and sorrow are closest to the surface – but no one is invulnerable.

(…)