which happened, it happened and happened

pattern light, bright lattice bright

whose eye had burst insomnia

F

(…)

F

(…)

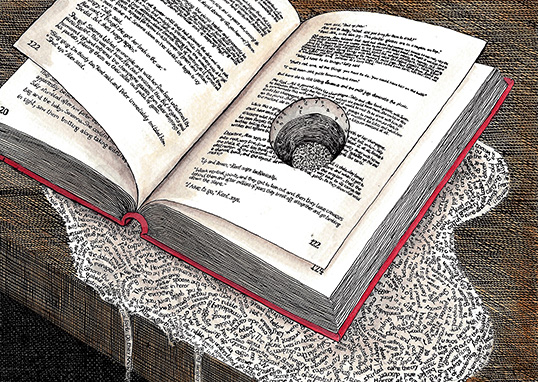

Translating is beautiful in autumn, when the days are short and I need to turn my desk lamp on earlier. Natural light distracts me a little; it lights up the room, all of the other books, the furniture, the curtains . . . Here, in this circle of white light that isolates me, we are truly alone, the sentences and I. For every book I have translated, I could tell you what was happening inside this room and in the outside world. This would, I imagine, be anything but interesting, and yet my life has accompanied the life of the words I have looked up, and it has, for me, not been easy to keep them in check.

As a young woman I translated while in a little white room with no wardrobe, on a bare table, and near a phone that kept interrupting me, that kept dragging me outside to the thousands of things that I had asked others to expect of me. I had yet to come to terms with the slowness translation imposes; I remember trying to invent ways to go faster. I was convinced that experience would make me faster. I would often get frustrated. I would find almost every text repetitive, almost every author a little bit wordy.

Then I discovered that experience does not, in any way, make translation faster, but it does heal impatience and our need for the phone to ring.

At the time, I remember, I was fresh out of university and full of literary enthusiasm, and I swathed the words of the Brontë sisters in my own voice. I experienced the difficulty of having to combine the spontaneity of the simple letters between the sisters and their friends, and the intense richness of those extraordinarily captive and yet free women.

(…)

Elza. Together we ate grapes and washed them down with rosé. The next day I discovered a moist grape stem in my pocket. It looked like an undecorated Christmas tree.

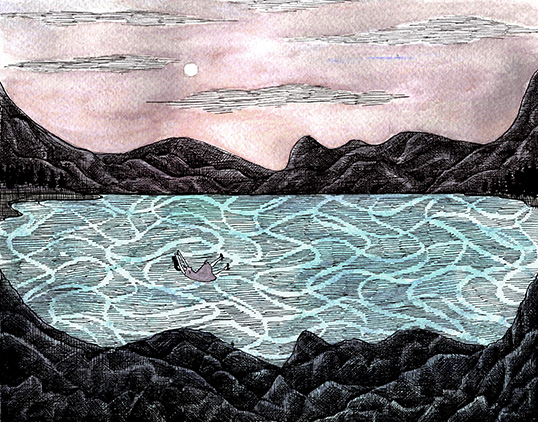

Kalisto Tanzi vanished from the city, which had been hit by a heat wave. The heat radiated from the houses and streets burning people’s faces, and the scorching town seared its brand onto their foreheads.

I stopped in front of the theater window so I could read Kalisto’s name on the posters and confirm to myself that he did actually exist. I enjoy pronouncing his name, which tormented him throughout childhood and puberty and only stopped annoying him after my arrival. I walk slowly to the other end of the city, the muscles in my legs shake slightly in the hot air. It’s noon. The only things on the planet that are really moving are drops of sweat. They run down to the base of the nose and then spurt out again under my hair.

I’m going to buy poison.

Ian saw a rat in the crapper last night.

The rat-catcher has a wine cellar underneath his store. Underground we escape the unbearable heat and drink. He’s telling me how intelligent the rats are.

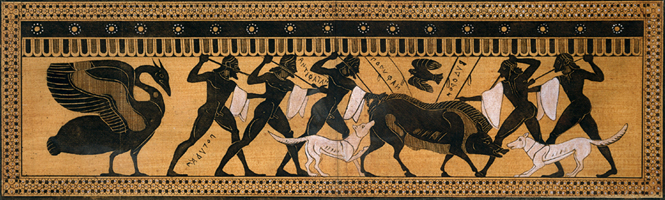

“They have a taster, who tastes food first. When it dies, the others won’t even touch the bait. So we now offer the next generation of rat bait. The rat only begins to die four days after consuming the poison. It dies from internal bleeding. Even Seneca confirmed that this sort of death is painless. The other rats think their compatriot has died a natural death. But even so, if several of them die in a short time, they’ll evaluate the place as unacceptable because of the high mortality rate and move elsewhere. This gift of judgment is completely missing in some people, or even whole nations.”

(…)

I studied psychology in a big, gloomy Communist city. My department was located in a building that had been the headquarters of an S.S. unit during the war. That part of the city had been built up on the ruins of the ghetto, which you could tell if you took a good look—that whole neighborhood stood about three feet higher than the rest of the town. Three feet of rubble. I never felt comfortable there; between the new Communist buildings and the paltry squares there was always a wind, and the frosty air was particularly bitter, stinging you in the face. Ultimately it was a place that still, despite construction, belonged to the dead. I still have dreams about the building where my classes were—its broad hallways that looked like they’d been carved into stone, smoothed down by people’s feet, the worn edges of the stairs, the handrails polished by people’s hands, traces imprinted in space. Maybe that was why we were haunted by those ghosts.

When we’d put rats in a maze, there was always one whose behavior would contradict the theory and would refuse to care about our clever hypotheses. It would stand up on its little hind legs, absolutely indifferent to the reward at the end of our experimental route; disdaining the perks of Pavlovian conditioning, it would simply take one good look at us and then turn around, or turn its attention to the unhurried exploration of the maze. It would look for something in the lateral corridors, trying to attract attention. It would squeak, disoriented, and then the girls, despite the rules, would usually take it out and hold it in their hands.

The muscles of a dead, splayed frog would flex and straighten to the rhythm of electrical pulses, but in a way that had not yet been described in our textbooks—it would gesture to us, its limbs making clear signs of threats and taunts, thereby contradicting our hallowed faith in the mechanical innocence of physiological reflexes.

Here we were taught that the world could be described, and even explained, by means of simple answers to intelligent questions. That in its essence the world was inert and dead, governed by fairly simple laws that needed to be explained and made public—if possible with the aid of diagrams. We were required to do experiments. To formulate hypotheses. To verify. We were inducted into the mysteries of statistics, taught to believe that equipped with such a tool we would be able to perfectly describe all the workings of the world—that ninety percent is more significant than five.

But if there’s one thing I know now, it’s that anyone looking for order ought to steer clear of psychology altogether. Go for physiology or theology instead, where at least you’ll have solid backing—either in matter or in spirit—instead of psychology’s slippery terrain. The psyche is quite a tenuous object of study.

It turned out it was true what some people said about psychology being a major you choose not because of the job you want, or out of curiosity or a vocation to help others, but rather for another very simple reason. I think all of us had some sort of deeply hidden defect, although we no doubt all gave the impression of intelligent, healthy young people—the defect was masked, skillfully camouflaged at our entrance exams. A ball of tautly tangled emotions breaking down, like those strange tumors that turn up sometimes in the human body and that can be seen in any self-respecting museum of pathological anatomy. Although what if the people who administered our exams were the same sort of people, and in reality they knew exactly what they were doing? In that case, we would be their direct heirs. When, in our second year, we discussed the function of defense mechanisms and found that we were humbled by the power of that portion of our psyche, we began to understand that if it weren’t for rationalization, sublimation, denial—all the little tricks we let ourselves perform—if instead we simply saw the world as it was, with nothing to protect us, honestly and courageously, it would break our hearts.

What we learned in college was that we are made up of defenses, of shields and armor, that we are cities whose architecture essentially comes down to walls, ramparts, strongholds; bunker states.

Every test, questionnaire, and study we conducted on each other, as well, so that by the time we got through our third year I had a name for what was wrong with me; it was like discovering my own secret name, the name that summons one to an initiation.

(…)

Schubert the Greek

Is it a new birth,

insomnia’s sediments

from feathers, memories,

and bullets?

A new departure, a counter-departure.

There is no equality yet between

snow’s shadow and shadow’s ash.

Should one take refuge in Narcissus (or Bacchus)

for the sake of decoding the talismanic rose

or the butterflies that flit

in the corridors opened by our sleep

that fossilize us?

How distant are the paved roads of childhood.

How close are the roads of death.

Greek sculptures are capable of

the liquidation of minds that alienation’s echo

filled with dirt.

Schubert once more, and the tears are not enough.

It is our duty to toss the keys into the President’s hands.

The Shade

Bore deeper into your aversion, O reality,

as that might be more becoming for the ripping up of the stars.

Stars! A foot in search of something that resembles it. A foot that sprouts leaves with dreams. A foot that severs.

The axe that was crafted to cut trees trunks will remain an axe always.

The final arrival to the realm of my arms was on Tuesday.

Between rain and reality, god’s shadow

descends.

Here I am, en route to practice my humanity.

The room is box-shaped, just like the heart,

With the last of my cigarettes, anxiety reaches its most ferocious state.

I descend.

(…)