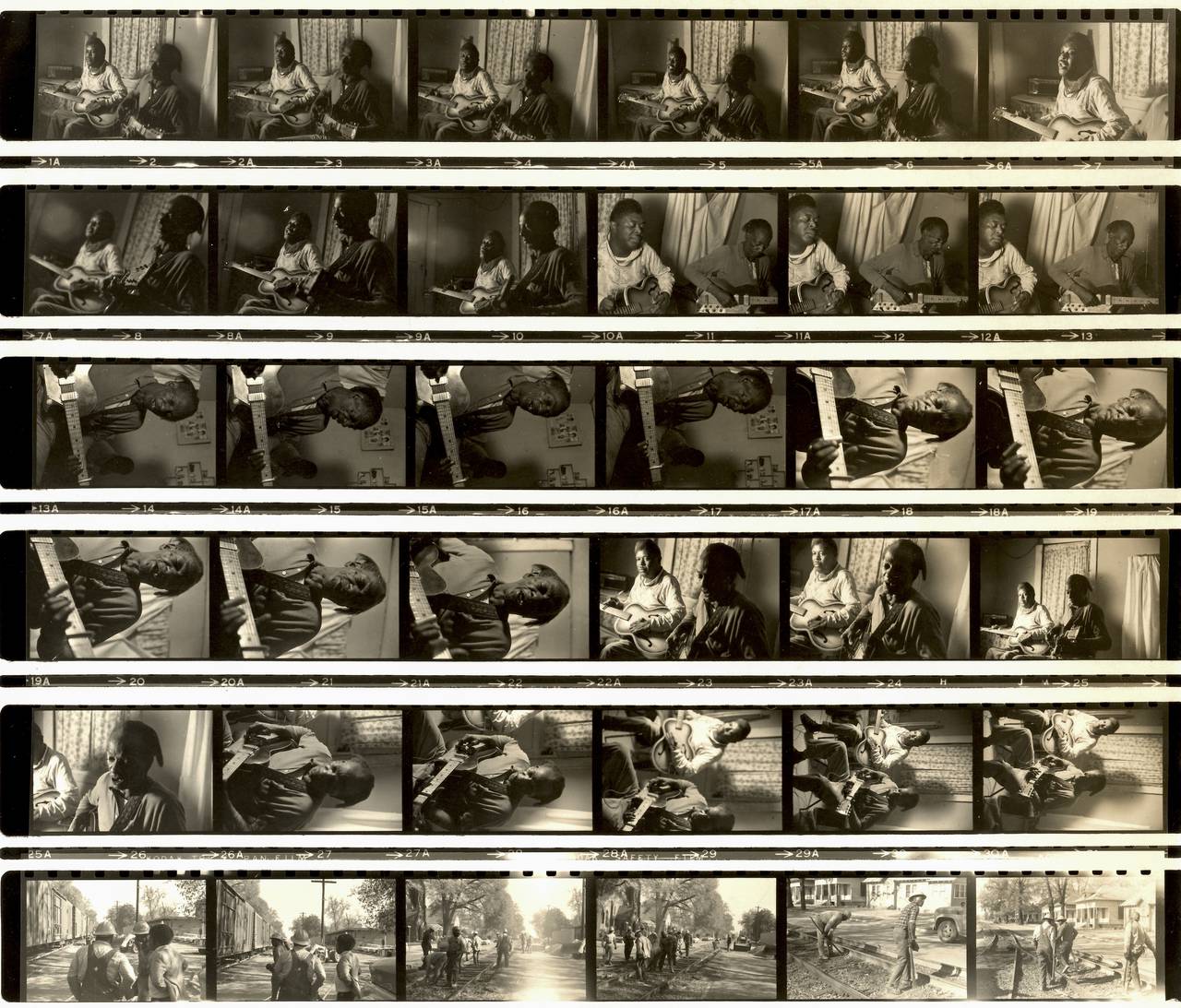

IN THE WORLD of early-20th-century African-American music and people obsessed by it, who can appear from one angle like a clique of pale and misanthropic scholar-gatherers and from another like a sizable chunk of the human population, there exist no ghosts more vexing than a couple of women identified on three ultrarare records made in 1930 and ’31 as Elvie Thomas and Geeshie Wiley. There are musicians as obscure as Wiley and Thomas, and musicians as great, but in none does the Venn diagram of greatness and lostness reveal such vast and bewildering co-extent. In the spring of 1930, in a damp and dimly lit studio, in a small Wisconsin village on the western shore of Lake Michigan, the duo recorded a batch of songs that for more than half a century have been numbered among the masterpieces of prewar American music, in particular two, Elvie’s “Motherless Child Blues” and Geeshie’s “Last Kind Words Blues,” twin Alps of their tiny oeuvre, inspiring essays and novels and films and cover versions, a classical arrangement.

Yet despite more than 50 years of researchers’ efforts to learn who the two women were or where they came from, we have remained ignorant of even their legal names. The sketchy memories of one or two ancient Mississippians, gathered many decades ago, seemed to point to the southern half of that state, yet none led to anything solid. A few people thought they heard hints of Louisiana or Texas in the guitar playing or in the pronunciation of a lyric. We know that the word “Geechee,” with a c, can refer to a person born into the heavily African-inflected Gullah culture centered on the coastal islands off Georgia and the Carolinas. But nothing turned up there either. Or anywhere. No grave site, no photograph. Forget that — no anecdotes. This is what set Geeshie and Elvie apart even from the rest of an innermost group of phantom geniuses of the ’20s and ’30s. Their myth was they didn’t have anything you could so much as hang a myth on. The objects themselves — the fewer than 10 surviving copies, total, of their three known Paramount releases, a handful of heavy, black, scratch-riven shellac platters, all in private hands — these were the whole of the file on Geeshie and Elvie, and even these had come within a second thought of vanishing, within, say, a woman’s decision in cleaning her parents’ attic to go against some idle advice that she throw out a box of old records and instead to find out what the junk shop gives. When she decides otherwise, when the shop isn’t on the way home, there goes the music, there go the souls, ash flakes up the flue, to flutter about with the Edison cylinder of Buddy Bolden’s band and the phonautograph of Lincoln’s voice.

I have been fascinated by this music since first experiencing it, like a lot of other people in my generation, in Terry Zwigoff’s 1994 documentary “Crumb,” on the life of the artist Robert Crumb, which used “Last Kind Words” for a particularly vivid montage sequence. And I have closely followed the search for them over the years; drawn along in part by the sheer History Channel mysteriousness of it, but mainly — the reason it never got boring — by their music.

Outside any bullyingly hyperbolical attempts to describe the technical beauty of the songs themselves, there’s another facet to them, one that deepens their fascination, namely a certain time-capsule dimension. The year 1930 seems long ago enough now, perhaps, but older songs and singers can be heard to blow through this music, strains in the American songbook that we know were there, from before the Civil War, but can’t hear very well or at all. There’s a song, Geeshie’s “Last Kind Words,” a kind of pre-blues or not-yet-blues, a doomy, minor-key lament that calls up droning banjo songs from long before the cheap-guitar era, with a strange thumping rhythm on the bass string. “If I get killed,” Geeshie sings, “if I get killed, please don’t bury my soul.” There’s a blues, “Motherless Child,” with 16-bar, four-line stanzas, that begins by repeating the same line four times, “My mother told me just before she died,” AAAA, no variation, just moaning the words, each time with achingly subtle microvariations, notes blue enough to flirt with tonal chaos. Generations of spirituals pass through “Motherless Child,” field melodies and work songs drift through it, and above everything, the playing brims with unfalsifiable sophistication. Elvie’s notes float. She sends them out like little sailboats onto a pond. “Motherless Child” is her only song, the only one of the six on which she takes lead to my ears — there are people who think it’s also her on “Over to My House.” On the other songs she’s behind Geeshie, albeit contributing hugely. The famous Joe Bussard (pronounced “buzzard”), one of the world’s foremost collectors of prewar 78s, found one of two known copies of “Motherless Child” in an antique store in Baltimore, near the waterfront, in the mid-1960s. The story goes that Bussard used to have people over to his house to play for them the first note of “Motherless Child,” just the first few seconds, again and again, an E that Elvie plucks and lets hang. It sounds like nothing and then, after several listens, like nothing else. “Baby, now she’s dead, she’s six feet in the ground,” she sings. “And I’m a child, and I am drifting ’round.”

Before there could be the minor miracle of these discs’ having survived, there had to be an earlier, major one: that of people like Geeshie and Elvie ever being recorded. To understand how that happened it’s needful to know about race records, a commercial field that flourished between the world wars, and specifically the Paramount company, a major competitor in that game throughout the 1920s.

A furniture company, that’s how it started. The Wisconsin Chair Company. They got into making phonograph cabinets. If people had records they liked, they would want phonographs to play them on, and if they had phonographs, they would want cabinets to keep them in. The discs were even sold, especially at first, in furniture shops. They were literally accessories. Toys, you could say. In fact, the first disc “records” were manufactured to go with a long-horned gramophone distributed by a German toy company. So we must imagine, it’s as if a subgenre of major American art had been preserved only on vintage View-Master slides.

In 1920, when the white-owned OKeh label shocked even itself by selling hundreds of thousands of copies of Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” (the first blues recorded by an African-American female vocalist), the furniture-phonograph complex spied a chance. Two populations were forming or achieving critical mass, whites willing to pay for recordings of black music and blacks able to afford phonographs, and together they made a new market. It’s around then that the actual phrase “race records” enters the vernacular. In 1926, Paramount had game-changing luck on a string of 78s showcasing the virtuosic Texas songster Blind Lemon Jefferson — his “Long Lonesome Blues” sold into the six figures — and as in Mamie Smith’s case, he touched off a frantic search among labels to find performers in a similar vein. The “country blues” was born, though not yet known by that name. It was men, for the most part, but with an important female minority, a “vital feminizing force,” in the words of Don Kent, the influential collector and poet of liner notes.

For the preserving of that force we have to thank not the foresight of those recording companies but their ignorance and even philistinism when it came to black culture. They knew next to nothing about the music and even less about what new trends in it might appeal to consumers. Nowhere was this truer than at Paramount. These were businessmen, Northern and Midwestern, former salesmen. Their notions of what was a hit and what was not were a Magic Eight Ball. So, when the mid-1920s arrived, and Paramount went looking farther afield for new acts, they compensated by recording everything and waiting to see what sold. Not everything, but a lot. A long swath of everything. The result was an unprecedented, never-to-be-repeated, all-but-unconscious survey of America’s musical culture, a sonic X-ray of it, taken at a moment when the full kaleidoscopic variety of prerecording-era transracial forms hadn’t yet contracted. Hundreds of singers, more thousands of songs. Some of the greatest musicians ever born in this country were netted only there. It was a slapdash and profit-driven documentary project that in some respects dwarfed what the most ambitious and well intentioned ethnomusicologists could hope to achieve (deformed in all sorts of ways by capitalism, but we take what we can get).

Among the first to wake up to these riches was, as it happens, the most prominent of those great ethnomusicologists, Alan Lomax. He had been traveling the back roads with his father, John A. Lomax, making field recordings for the Library of Congress’s Archive of American Folk Song, and he had seen firsthand that all of this culture, which had endured mouth-to-ear for centuries, was giving way, proving not quite powerful enough to resist the radio waves and movies. In the late ’30s, Lomax was record hunting one day and came across a large cache of old Paramount discs in a store. At the time they were a mere 10 or 15 years old and couldn’t have appeared less valuable to a casual picker. Lomax listened, transfixed by an increasing realization that Paramount offered him an earhole into the past, into the decade just before he joined his father on the song-collecting scene, an enormous commercial complement to what the two of them had been doing under intellectual auspices with their field-recording. Lomax started digging. In 1940 he created a list, with the title “American Folk Songs on Commercial Records,” and circulated it in the folklore community.

This list is a very precious little document in 20th-century American cultural history. It was published in only a limited library report, but copies were passed around. It marked the first time someone had publicly recognized these commercial recordings as something other than detritus. Most important, it made space for, even emphasized, the more obscure blues singers.

To grasp the significance of that, you have to bear in mind how fantastically few record collectors possessed such an interest at the end of the 1930s. Early jazz was a thing in certain hip circles, but only a few true freaks were into the country blues. There was twitchy, rail-thin Jim McKune, a postal worker from Long Island City, Queens, who famously maintained precisely 300 of the choicest records under his bed at the Y.M.C.A. Had to keep the volume low to avoid complaints. He referred to his listening sessions as séances. Summoning weird old voices from the South, the ethereal falsetto of Crying Sam Collins. Or the whine of Isaiah Nettles, the Mississippi Moaner. Did McKune listen to Geeshie and Elvie? It’s unknowable. His records were already gone when he died — murdered in 1971, in a hotel room. Another early explorer? The writer Paul Bowles. The Paul Bowles, believe it or not, who started collecting blues records as an ether-huffing undergraduate in Charlottesville, Va., in the late 1920s, “at secondhand furniture stores in the black quarter.” Out West there was Harry Smith, who went on to create the “Anthology of American Folk Music” for Folkways Records, the first “box set,” of which it can be compactly if inadequately said: No “Anthology,” no Woodstock. Wee, owlish Smith. He and McKune came to know each other. No less important, they both came to know Alan Lomax’s list, which galvanized their passion for this particular chamber of the recorded past, giving shape to their “want lists.”

In the ’50s McKune would become a sort of salon master to the so-called Blues Mafia, the initial cell of mainly Northeastern 78-pursuers who evolved, some of them, into the label owners and managers and taste-arbiters of the folk-blues revival. An all-white men’s club, several of whom were or grew wealthy, the Blues Mafia doesn’t always come off heroically in recent — and vital — revisionist histories of the field, more of them being written by women (including two forthcoming books by Daphne Brooks and Amanda Petrusich). Still, no one who seriously cares about the music would pretend that the cultural debt we owe the Blues Mafia isn’t past accounting. It’s not just all they found and documented that marks their contribution. It’s equally what they spawned, whether they would claim it or not. Dylan didn’t listen to 78s, after all, on the floors of those pads he was crashing at in Greenwich Village, but to the early reissue LPs. By Dylan I mean the ’60s. But also Dylan. “If I hadn’t heard the Robert Johnson record when I did,” he wrote 10 years ago, “there probably would have been hundreds of lines of mine that would have been shut down.”

(…)