(…)

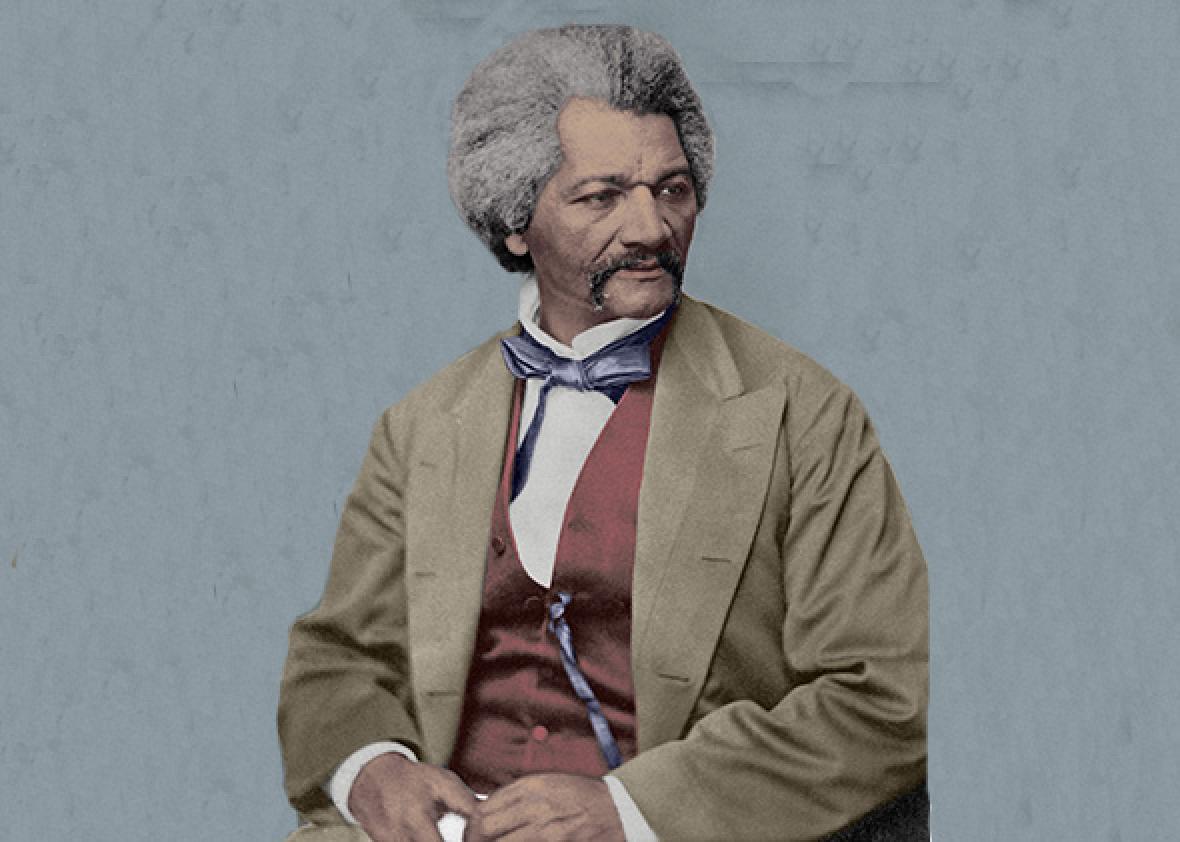

The speech that deserves our notice, and did truly thunder, came not at the centennial but a quarter of a century earlier, in Rochester, New York, on July 5, 1852. Rochester was the epicenter of the so-called burned-over district, a region along the Erie Canal swept repeatedly by religious revivals and reform. There, the former slave and ardent abolitionist Frederick Douglass published his newspaper the North Star. Douglass was a good friend of Susan B. Anthony, whose family farm was located on Rochester’s outskirts. His paper had been one of the few to support the women’s rights convention in nearby Seneca Falls, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1848.

So it was natural enough that the Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester asked Douglass to provide an oration for Independence Day. Since the Fourth that year fell on a Sunday, commemorations were held a day later. That suited Douglass perfectly, as African Americans had been celebrating the Fourth a day later for over two decades. Many blacks found the idea of joining in the festivities problematic at best, so long as white Americans continued to keep millions of slaves in chains. In any case, white revelers on the Fourth had a history of disrupting black processions. Many blacks made July 5 their holiday instead.

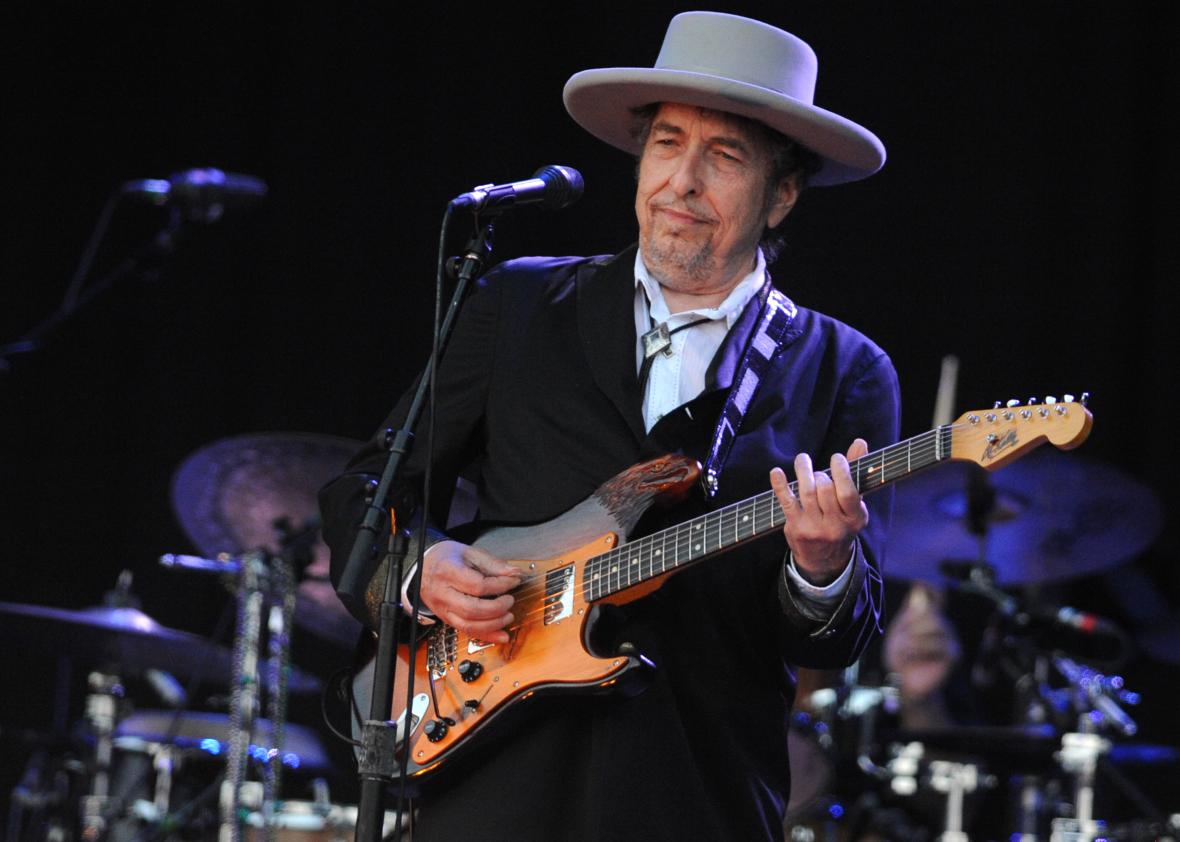

Though he was a newspaper publisher, Douglass believed that the spoken word remained the most effective way to move multitudes. As a boy he had secretly studied rhetoric and parsed the speeches of famous orators, though his first efforts at public speaking were modest. “It was with the utmost difficulty that I could stand erect,” he recalled, “or that I could command and articulate two words without hesitation and stammering.” Confidence came with time and practice.

Douglass also possessed a sense of humor—“of the driest kind,” observed one listener. “You can see it coming a long way off in a peculiar twitch of his mouth.”Occasionally he dramatized conversations to make a point, provoking laughter when he mimicked the drawl of a Southern planter.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton vividly recalled the first time she heard Douglass address a crowd. He stood over 6 feet tall, “like an African prince, majestic in his wrath. Around him sat the great antislavery orators of the day, earnestly watching the effect of his eloquence on that immense audience, that laughed and wept by turns, completely carried away by the wondrous gifts of his pathos and humor. On this occasion, all the other speakers seemed tame after Frederick Douglass.”

In Rochester, Douglass stalked his largely white audience with exquisite care, taking them by stealth. He began by providing what many listeners might not have expected from a notorious abolitionist: a fulsome paean to the Fourth and the founding generation. The day brought forth “demonstrations of joyous enthusiasm,” he told them, for the signers of the Declaration were “brave men. They were great men too—great enough to give fame to a great age.” Jefferson’s very words echoed in Douglass’s salute: “Your fathers staked their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor, on the cause of their country … ”

(…)