In high school, writing term papers on the family PC, I’d often turn to Microsoft Word’s “readability statistics” feature to make sure I sounded smart enough. With a few clicks, Word assigned my papers a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level: a number from one to twelve indicating how many years of education the average reader would need to have completed in order to decipher my language. I had no idea how Word made this calculation, but I noticed that it rewarded prolix sentences with a higher “grade.” So that’s what I wrote. I put my every word choice under close scrutiny. Soon my paragraphs buckled under the weight of clauses and polysyllables, but I, a ninth grader, was generating prose that only twelfth graders could read—which made me pretty hot shit, my thinking went.

Those Flesch-Kincaid trials came back to me as I read “Nabokov’s Favorite Word Is Mauve: What the Numbers Reveal About the Classics, Bestsellers, and Our Own Writing,” by Ben Blatt, which looks at the canon as a statistical gold mine to be dredged for patterns, variances, and singularities. In “literary experiments” on diction, punctuation, cliffhangers, clichés, and other aspects of style and usage, Blatt uses data to probe the body of conventional wisdom that surrounds creative writing. What if those who allegedly loathe adverbs are actually completely, totally addicted to them? What if it’s quite O.K. to use intensifiers very often, because Jane Austen is rather fond of them? What if I like exclamation points! Blatt’s jacket bio cites “his fun approach to data journalism”—a bit of prolepsis, maybe, aimed at those of us who’d sooner watch paint dry than look at anything quantitatively—and his book is laden with charts, lists, and tables printed in a gentle purple. The lessons here are valuable because of their workmanlike cast, not in spite of it. Put aside the “fun approach” and “Mauve” makes some enticingly heretical observations: that every great writer is a technician, every novel a mere agglomeration of prose effects.

The book is built on agreeable miscellany, and parts of it are willfully trivial. On the face of it, there’s not much to be gleaned from the fact that James Joyce uses 1,105 exclamation points per hundred thousand words, or that J. R. R. Tolkien leans too often on “suddenly,” that most accursed of adverbs. Blatt’s findings are more absorbing when he ditches the bean-counter approach. American writers of Harry Potter fan fiction are actually more liable to use “brilliant” than their British counterparts, who employ the word with native agility. And, in a study of erotica written by New Yorkers, Blatt notes a preponderance of the following words: subway, popsicle, senator, butthole, museum, landlord, thrusted, Jacuzzi, sin, and shrugs. Most of these choices are intuitive, even laudable—but what explains those last three? I grasp that a New Yorker might lust for a senator with a popsicle in his butthole; a shrugging sinner in a hot tub doesn’t quite rate.

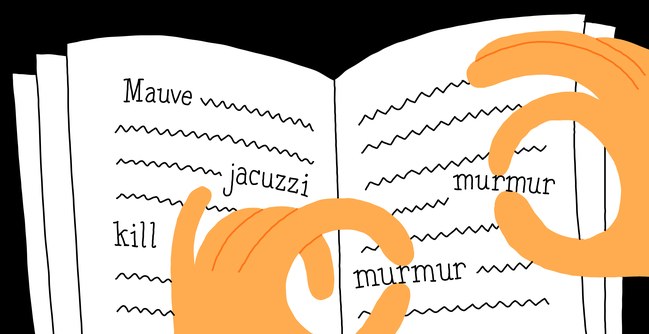

Blatt’s research on diction and gender is especially revelatory. Looking at a broad swath of twentieth-century lit, he tallies the verbs most often used to describe one gender over another. The results find rich deposits of sexism running through the language. Male characters are most likely to mutter, grin, shout, chuckle, and kill; women are doomed to shiver, weep, murmur, scream, and marry. Male authors are far likelier to write “she interrupted” than “he interrupted.” A grim typology begins to emerge. Men are raffish, jolly, murderous sorts, while women are delicate and meek, except when they deign to interrupt men, as they often do. There’s some sexual self-loathing across the board, too: when writers assign verbs to someone of the opposite gender, they most often reach for “kiss,” “exclaim,” “answer,” “love,” and “smile”; characters of the same gender “hear,” “wonder,” “lay,” “hate,” and “run.”

The high point of the book is Blatt’s effort “to test whether something like a literary fingerprint exists for famous writers.” It does, he finds—across their oeuvres, “authors do end up writing in a way that is both unique and consistent, just like an actual fingerprint is distinct and unchanging.” Even the way that writers deploy simple pairs of words—“and” and “the,” “these” and “then,” “what” and “but”—is often enough to identify them. The numbers bear out a romantic idea: that a writer is always ineluctably herself. Soon, Blatt zeroes in on writers’ “favorite” words—hence his title, indicating Nabokov’s predilection for “mauve.” The words must be used in half an author’s books, at least once per hundred thousand words; they can’t be proper nouns. His discoveries are startlingly apt. Almost without fail, the words evoke their authors’ affinities and manias. John Cheever favors “venereal”—a perfect encapsulation of his urbane midcentury erotics, tinged with morality. Isaac Asimov prefers “terminus,” a word ensconced in a swooping, stately futurism; Woolf has her “mantelpiece,” Wharton her “compunction.” (Melville’s “sperm” is somewhat misleading, perhaps, when separated from his whales.)

Cumulatively, these facts and figures make “Mauve” an effective craft book. By reminding us that literature is just strings of words and punctuation, Blatt has taken the whiff of the godhead out of it. Writers like to emphasize the psychology in their work, their strenuous labor toward depth and verisimilitude; they’re less inclined to talk about how few decent synonyms exist for “good.” The stats speak a cold truth: there are dozens of prosaic choices behind every artful sentence. Dwelling on this can inoculate writers against the preciousness of the workshop. “Mauve” has no truck with showing instead of telling, no druthers about sense of place or voice. Even in great books, it says, one word follows another, all of them slaves to grammar, sequence, and probability.

(…)