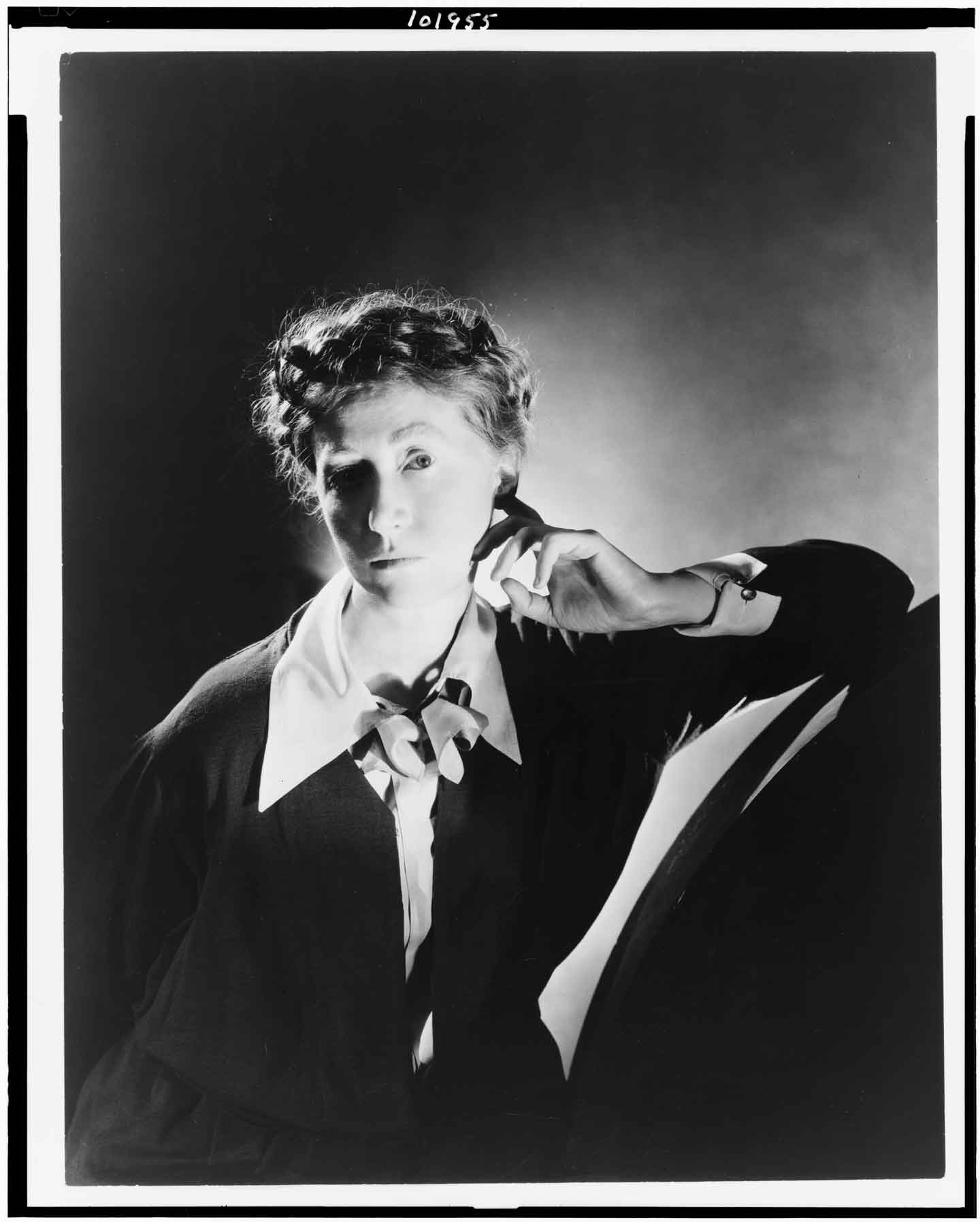

Han Kang is a disquieting storyteller who leads the reader into the very heart of human experience, where the singular crosses the universal. Author of ten books of fiction and poetry in her native Korean, Han’s subversive work has been brought onto the Anglophone stage through close partnership with her award-winning translator Deborah Smith. Smith’s elegant renditions of the novels HUMAN ACTS (2016) and THE VEGETARIAN (2015) form part of a recent blossoming of international interest in Korean literature; Dalkey Archive’s Library of Korean Literature launched in 2013 and consists of 25 translations so far. Originally published as three novellas in South Korea nearly a decade ago, Han has said that THE VEGETARIAN was initially received as ‘very extreme and bizarre’ in Korea. It has since become a cult bestseller, with translation rights sold in twenty countries and its central novella ‘Mongolian Mark’ awarded the prestigious Yi Sang Literary Prize in 2005. HUMAN ACTS, her latest novel, was awarded the Korean Manhae Literary Prize last year, adding to her numerous other accolades.

‘I believe that humans should be plants.’ This line from the great modernist poet Yi Sang, written in the Korean script hangul banned under Japanese rule, reportedly obsessed Han during university and became the seed for THE VEGETARIAN. Yi’s dream-like images evoking the violence of imperialism upon the colonial subject are mirrored in Han’s surrealistic and painterly portrayal of a woman’s personal rebellion. The novel tells the story of Yeong-hye who, haunted by grotesque dreams, first gives up meat, then food altogether in a radical refusal of human cruelty and destruction. In a patriarchal society where vegetarianism is rare, Yeong-hye’s transgression eventually leads to her institutionalisation and force-feeding. Han’s life-long exploration of the themes of violence and humanity are here rooted in the anorexic body forming a provocative psychological portrait of a woman’s body politics.

HUMAN ACTS revisits these themes but pans out to the national stage, excavating the traumatic legacy of the Gwangju massacre in post-war Korean history. Opening in the Gwangju Commune, the action unfurls in the crucible of the 1980s student and worker-led democratic movement. In 1979 when military dictator Park Chung-Hee, the father of current president Park Geun-Hye, was assassinated his ‘protégé’, General Chun Doo-Hwan, succeeded him and extended martial law across the country, closing universities, restricting press freedom and banning political organising. On 18 May 1980 when students gathered in Gwangju to protest these measures, the government responded by sending in soldiers who opened fire on the crowds. A citizen army managed to eject the military presence and in the following days virtually the whole city joined together in creating an autonomous community comparable to the Paris Commune. The uprising endured for a few days until it was crushed by a US-approved military operation on 27 May that killed and injured thousands.

The massacre left a deep imprint in Korea’s cultural memory, in part because the truth around events was suppressed for years afterwards. Conservative accounts painted the incident as a Communist plot driven by North Korean sympathisers, and the death toll remains contested. ‘Gwangju’, Han says, has become another word ‘for all that has been mutilated beyond repair. The radioactive spread is ongoing.’ Thus HUMAN ACTS is a book with a banging door – it is fiction as a form of alternative historiography where the unresolved past pollutes the present. For Han, ‘Gwangju’ functions like a common noun denoting mankind’s capacity for acts of extreme violence in the same instance as acts of great humanity. Indeed, Korea’s tumultuous history has seen a succession of Gwangjus: there has been little closure, for example, for the Korean women forced into sexual slavery under Japanese colonial rule, or for the families separated by the Korean War that left the two Koreas divided by the Demilitarized Zone when the Cold War turned hot on the peninsular.

A language carries its culture on its back and Han deftly transports the myriad complexities of Korean history through her spare prose. Yet HUMAN ACTS, likeTHE VEGETARIAN, is often about the failure of language to adequately convey experience. In a striking scene, a survivor of torture asks, ‘Would you have been able to string together a continuous thread of words, silences, coughs and hesitations, its warp and weft somehow containing all that you wanted to say?’ Han certainly attempts to do so, both in her lyrical work and in this interview, conducted through email and translated by Deborah Smith.

Q. THE WHITE REVIEW — The history of Korea in the twentieth century is rich in trauma – why did you choose to write about the Gwangju Uprising in particular?

A. HAN KANG — The twentieth century has left deep wounds not only on Korea but on the whole of the human race. Because I was born in 1970 I experienced neither the Japanese occupation, which lasted from 1910 to 1945, nor the Korean War, which began in 1950 and was concluded with a cease-fire in 1953. I began to publish poetry and fiction in 1993, when I was twenty-three; that was the first year since the military coup d’état in 1961 that a president who was not from the army but a civilian came to power. Thanks to that, I and writers of a similar generation felt that we had obtained the freedom to investigate the interior of the human without the guilty sense that we ought instead to be making political pronouncements through our work.

So my writing concentrated on this interior. Humans will not hesitate to lay down their own lives to rescue a child who had fallen onto the train tracks, yet are also perpetrators of appalling violence, like in Auschwitz. The broad spectrum of humanity, which runs from the sublime to the brutal, has for me been like a difficult homework problem ever since I was a child. You could say that my books are variations on this theme of human violence. Wanting to find the root cause of why embracing the human was such a painful thing for me, I groped inside my own interior, and there I encountered Gwangju, which I had experienced indirectly in 1980.

[…]