(…)

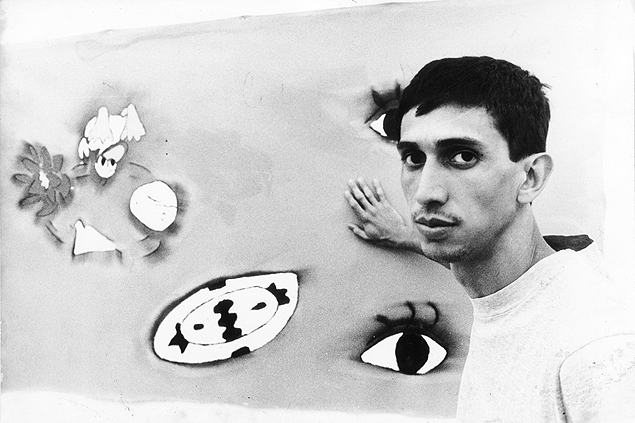

In Brazil, Leonilson is considered one of the most important artists of his generation. Born in the northeastern city of Fortaleza, he came of age in the 1980s, in the years immediately following Brazil’s twenty-year dictatorship. Emerging from oppressive times, he and his peers embraced the pleasures of painting, and they made bright and figurative work. But Leonilson’s art was also uniquely personal and literary; words float alone or in poetic arrangements (“here comes your man / full of numbers and words”). His presence looms over almost everything he left behind.

Leonilson died in 1993, at the age of thirty-six, of AIDs. He had learned of his illness only two years prior. As his health rapidly deteriorated, he shifted from painting to making small embroideries on pockets, bags, and bits of canvas. The Americas Society exhibition begins with these later, quietly beautiful works, and is framed around a quote by T. S. Eliot: “In my beginning is my end … In my end is my beginning.” An early 1975 self-portrait, made from denim jeans and with buttons for eyes, presages the introspective works Leonilson made in the last years of his life.

“I don’t make impersonal things,” he once said. He liked to paint the body: the brain, the lungs, and the heart. One painting from 1988 delineates human organs, with words flowing through and around them, including the phrase “the streets of the city.” The names of cities he visited—Madrid, Basel, Bordeaux—often appear in his art; but he was more a wanderer than a traveler.

“I am searching for something,” he said, “but I don’t know what I’m looking for.” Leonilson recorded these thoughts in his audio diaries, which he kept on tape cassettes from 1990 until his death three years later. He talks about the time he watched the Wim Wenders film Paris, Texas, and how lost the main character appears as he aimlessly walks the desert. Leonilson breaks down into tears, recognizing himself.

His audiotapes weren’t discovered until after he died. In 2015, Carlos Nader, a friend of Leonilson’s, made them into a film titled The Passion of JL. The incredibly moving project, which screened this Thursday at the New School in New York, is narrated solely by Leonilson’s voice, while images of his art flash on the screen. The tapes reveal someone full of feeling and desperately in search of love. “Why am I so alone? Why don’t I have a boyfriend?” he asks. “I am needy.”

Leonilson’s friends remember him as warm and gregarious. Many people, including Carlos Nader, have said the voice of the audiotapes is not the one they knew, but one that, in retrospect, illuminates his art.

*

I went to the Americas Society exhibition after I saw The Passion of JL. As I walked through the galleries, I heard the disembodied voice of Leonilson’s tapes (“love is the best thing there is”; “I think I will live long”; “I’m not afraid of dying, but of suffering”). I imagined his wounds as I counted the thirty-four tallies that look like stitches in the piece 34 with scars. I wondered if he had cheated or been the one betrayed as I read the word “traitor,” sewn above a sea of crystals. I figured he had cobbled these works together in utter silence, and likely alone.

In 1991, the year Leonilson was diagnosed with HIV, he made the work Empty Man. He used a found piece of linen depicting the children’s tale of the tortoise and the hare racing in a field. Beneath the scene, he stitched the words “salt. blood. salive,” and below that, a man’s torso surrounded by the broken-up phrase, “empty man / lone / ready.” Echoes of this empty, lone man appear elsewhere: the name José stitched in the corner of a faded green rectangle, a single figure labeled as an “island,” and most poetically, the word nobody, sewn on the edge of a pink pillow.

(…)