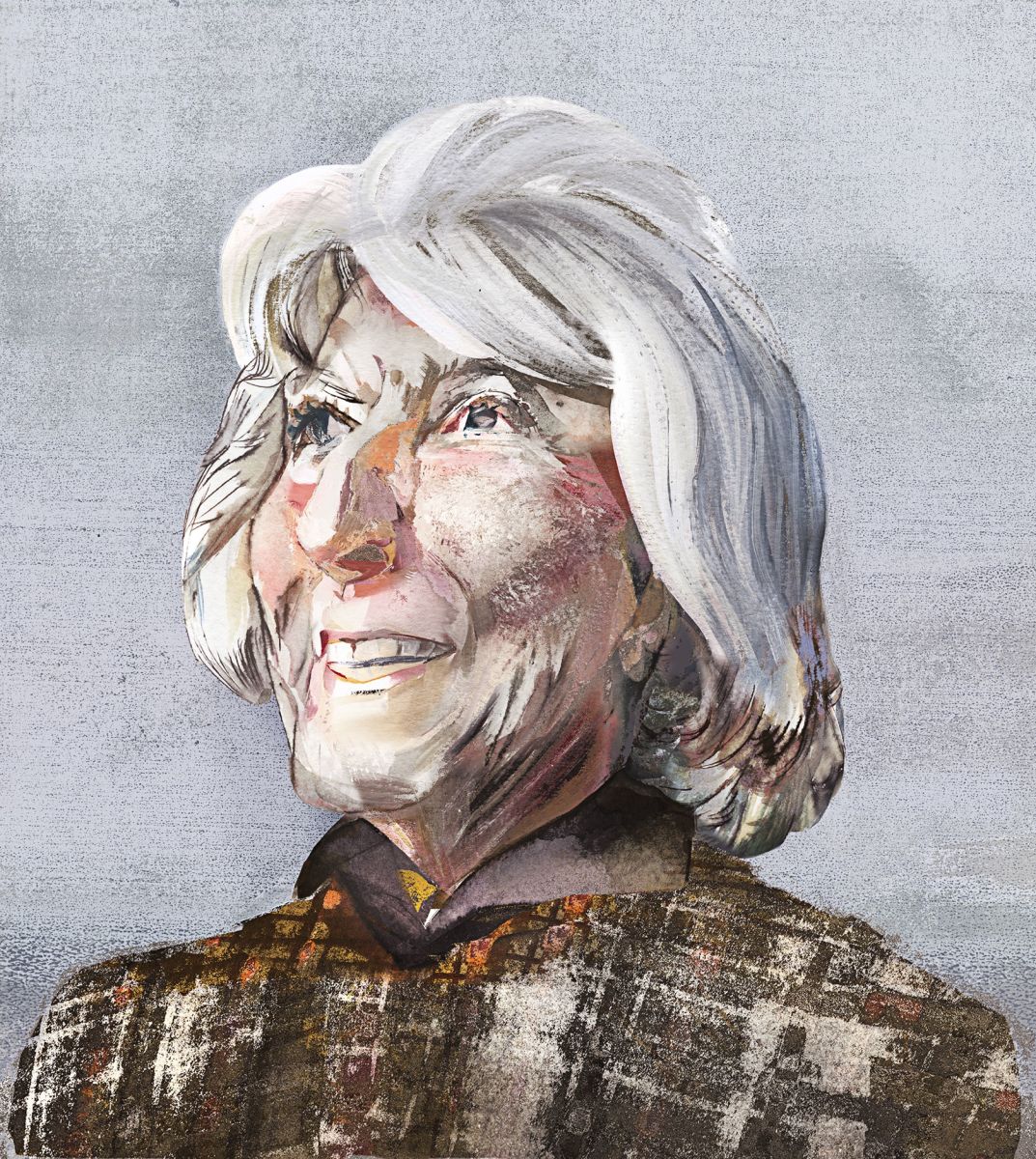

The Australian novelist Elizabeth Harrower, who is eighty-six and lives in Sydney, has been decidedly opaque about why she withdrew her fifth novel, “In Certain Circles” (Text), some months prior to publication, in 1971. Her mother, to whom she was very close, had died suddenly the year before. Harrower told Susan Wyndham, who interviewed her a few months ago in the Sydney Morning Herald, that she was absolutely “frozen” by the bereavement. She also claims to remember very little about her novel—“That sounds quite interesting, but I don’t think I’ll read it”—and adds that she has been “very good at closing doors and ending things. . . . What was going on in my head or my life at the time? Fortunately, whatever it was I’ve forgotten.” Elsewhere, Harrower has cast doubt on the novel’s quality: “It was well written because once you can write, you can write a good book. But there are a lot of dead novels out in the world that don’t need to be written.”

Harrower deposited the manuscript of “In Certain Circles” in the National Library of Australia and essentially terminated her literary career. She has said that she thinks of her fiction as something abandoned long ago, buried in a cellar. She can’t now be bothered with writing. “I don’t know anybody who knows I’m a writer,” she said in 2012. In 1971, plenty of people knew Harrower was a writer. The novelist Christina Stead, for one, declared that Harrower’s “The Long Prospect” (1958) “has no equal in our writing.” But obscurity is a fast worker, when properly paid: by the early nineteen-nineties, all her novels were out of print. Patrick White, who urged Harrower to keep working, once inscribed a book to her with the injunction “To Elizabeth, luncher and diner extraordinaire. Sad you don’t also WRITE.”

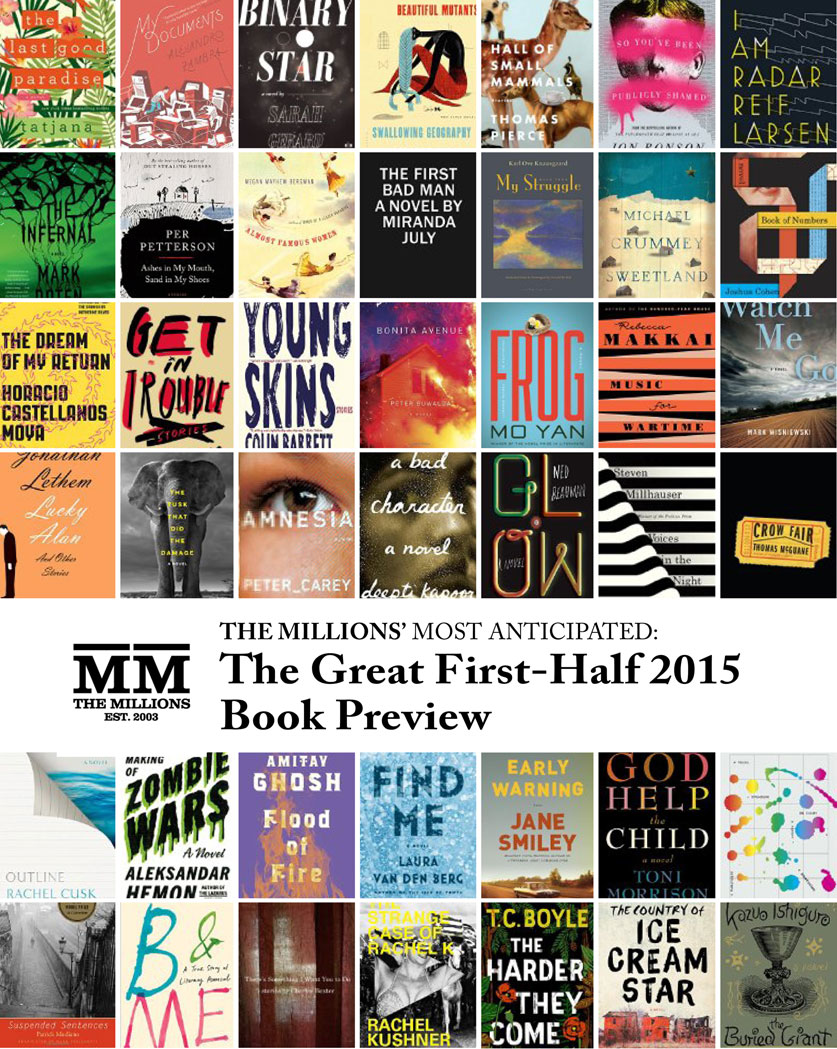

Her work might still be out of print if Michael Heyward and Penny Hueston, a married couple who run the Australian publishing house Text, hadn’t decided to start republishing it in 2012. They began with Harrower’s greatest novel, “The Watch Tower” (1966), the bitter story of two sisters, Laura and Clare, who lose their parents and fall under the sway of Felix Shaw, an abusive and controlling drunk. Over the next two years, Text published the rest of Harrower’s earlier work: “Down in the City” (1957), her first novel, and “The Long Prospect” (1958), her second, both of which she wrote in London; and “The Catherine Wheel” (1960), her third book. “In Certain Circles,” the withdrawn novel, was clearly the publisher’s most precious quarry. Heyward cajoled Harrower into letting him read the manuscript. She had not read any of her own work in forty years, and suspected that she might have to die before it was read again. Heyward thought the novel “extraordinary,” and Harrower agreed to its publication, perhaps figuring that death was a steep penalty for a comprehensive backlist.

Harrower’s writing is witty, desolate, truth-seeking, and complexly polished. Everything (except feeling, which is passionately and directly confessed) is controlled and put under precise formal pressure. Her sentences, which have an unsettling candor, launch a curling assault on the reader, often twisting in unexpected ways. And although her novels can feel somewhat closed, and tend to repeat themselves in theme, her prose is full of variety. She can be bracingly satirical: “The piercing soprano she raised at parties was understood to be her most prized asset, and had won her much applause.” She is generally tart. In “The Catherine Wheel,” a novel narrated by a young Australian woman living in a London bed-sit, a single glance at the room’s furniture tells us much about her self-esteem: “Above it was a mirror, undistorted, except perhaps—I’d already noticed—on the side of flattery.” She can be savagely metaphorical: “She was like a park that had never once removed its Don’t Walk on the Grass signs.” But her wit often teeters on the edge of pain, as it does in that last sentence, which describes Laura and Clare’s vilely haughty mother in “The Watch Tower,” or as it does in this description of pretty, ingenuous Zoe Howard, who will marry disastrously in “In Certain Circles”: “It never mattered what she said to men: they liked her to say anything.” The sentences have an innocent composure, as if Harrower hoped to slip the pain past us: “Yet really, apart from the sense of irretrievable loss, there was nothing wrong at all.” “Really, it turned out to be like every other day, except that she never forgot it.” Zoe Howard, trapped in her painful marriage, standing by a swimming pool on a morning in which she and her husband have managed to effect a brief truce, is described thus: “She shivered and pulled on her towelling coat, prudently absent from past and future.” What pain lies in the coiled coda of that sentence! Sometimes, the reader has to decode Harrower’s careful irony: “He made a sound not like a laugh” (about a histrionic charmer who is feeling sorry for himself). But Harrower’s prose expands, too, to gather in the Australian landscapes: Sydney, the wide harbor, the narrower suburbs (easily dispatched in one novel as “weedy parks named after councillors”), the blue skies and breathing red outback, the “blue and legendary haze” that seems to hover over the whole world.

Harrower was right about “In Certain Circles” being well written, but surely wrong to take its superb style for granted, as if mere literary muscle memory. Like the rest of her work, the novel is severely achieved: the coolly exact prose cannot be distinguished from the ashen exhaustion of its tragic fires. The book suffers from a few structural difficulties (some weirdly compressed transitions, a couple of characters who never quite come into focus) that may have earned Harrower’s anxious scorn in 1971. But “In Certain Circles” also extends and deepens several of her persistent concerns: how easily we submit to cruelty and coercion; the relations between men and women in a frankly misogynist era; the moral imperative to tell the truth, to shatter the china niceties that sustain bourgeois domestic life. The book belongs with her best work, with “The Watch Tower” and “The Long Prospect.”