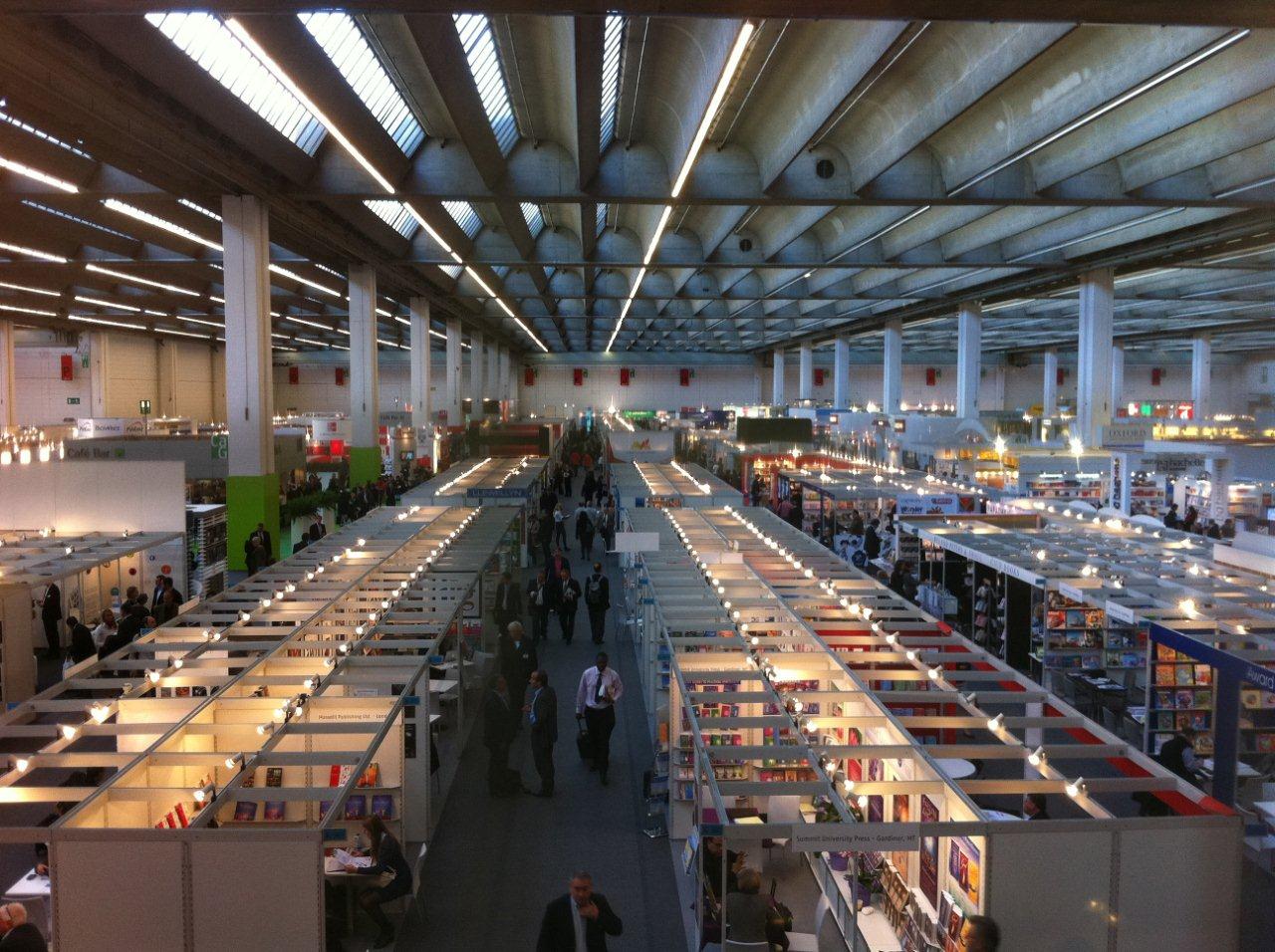

Wednesday morning is the first real day of the Fair, and I head straight to the distant hall eight, where I look for Bob Miller. In the early Nineties, Bob Miller founded Hyperion, Disney’s publishing company, where he became known for bringing out such inspiro-motivational titles as Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff… and It’s All Small Stuff and The Five People You Meet in Heaven. He left Hyperion this past spring and has since gotten a lot of press< for his new venture, a boutique imprint at HarperCollins called HarperStudio. One idea behind HarperStudio is to break the prisoners’ dilemma of contemporary corporate publishing by doing away with the huge advance: the imprint won’t offer any advances larger than a hundred grand. But any profits will be shared fifty-fifty with the writer. Nobody has any clue whether this will work, but everyone seems hopeful about it, and if Bob Miller shows even a little success there’s a good chance other houses will follow suit. I’ve had two conversations so far in Frankfurt in which he has been called a “hero.”

Bob is sort of my uncle. His mother is my grandfather’s second wife. I was, for complicated and typical family reasons, raised to be pretty skeptical of him, but over the past few years I’ve come to see him as a stand-up guy. His jokes aren’t always hilarious but he’s decent, supportive, and very well-intentioned, and I feel a touch of pride for all his book-business success, even if I probably won’t buy HarperStudio’s The 50th Law, a business-advice manual by the rapper 50 Cent. As Bob and I sit around at the HarperCollins booth, he keeps awkwardly introducing me as an “old friend,” because he’s not really sure about the protocol. I sit in on a few of his meetings and listen to him deliver his spiel to curious fellow publishers, most of them foreigners. People are consistently enthusiastic. Bob takes heart in the fact that he might help to reshape the industry along more reasonable lines. Also to his credit is the lack of vampire talk at his meetings, though at the surrounding tables there’s a lot of stuff about dogs. (“Dogs are big every year,” says Ira, bored.)

Bob and I head over to a meeting he has set up with Jamie Byng, the publisher of Canongate, a mid-size house based in Edinburgh. Jamie is sometimes called the “rock star of publishing,” but he’s a refined 1985 sort of rock star, like an Etonian Whitesnake. His father is the Eighth Earl of Strafford, and his stepfather, who ran the BBC for many years, is straight-up KBE. Jamie has a leonine aspect, with a high clear brow and soft curls eddying over his ears and along his collar. Today he’s wearing a graphite suit with a steeply angled ticket pocket over an open-necked cobalt shirt. He’s got a really plush lilt that approaches purring. The previous evening, when I first met Jamie, I told him that the only galley I wanted to take away from the Fair was Geoff Dyer’s forthcoming novel, which Canongate will publish this spring, and Jamie took one out of his distressed satchel and gave it to me, along with a CD of his favorite Nick Cave songs. He said that he and Dyer play tennis together, and that he read the first sixty pages of the acetate-wrapped, gold-and-black FSG hardcover of Out of Sheer Rage while half-drunk one late night in his library, standing up by the shelves, then sat down on the couch and finished the whole book in a “one-er.”

Canongate’s booth has a Chesterfield couch and a leather club chair, but Bob and Jamie and I are at a low table. Jamie’s talking about having republished a cult cocaine book from the Seventies called Snowblind, and how “Damien”—Damien Hirst—designed a limited-edition version. Damien’s idea was to use heavy steel-reinforced mirrors as the book’s covers, and for each book to come with a real hundred- dollar bill in a compartment drilled out of the pages and a steel fake AmEx-card bookmark. This was all during a period when Damien was seriously, like, interested in cocaine “as a thing.” They did a thousand copies and the book sold for a thousand pounds, though at Damien’s recent auction some copies went for fifteen hundred. Now Jamie is talking about Marc Quinn’s blood and more stuff about Damien—Bob and I are just rapt—and he interrupts himself—he is constantly interrupting himself—to say that he loves Bob’s business model and really hopes they can do some business together one day, even though HarperCollins UK will be publishing all the British editions of Bob’s books.

It’s never quite clear why this meeting has been scheduled. Jamie is considered to be Morgan Entrekin’s heir as the industry’s boulevardier, the standard-bearer of unanswerable élan. (The two men are close.) He takes risks with strange books and has built a house that’s got more brand identity than just about anyone else. He’s also been shrewd in buying up and repackaging cult books—like a U.K. reissue of Lewis Hyde’s The Gift, with blurbs from Zadie Smith and David Foster Wallace—that can be had on the cheap, and he knows his market for expensive limited-edition widgets: Damien won’t likely be designing any e-books in the near future. It is in some ways a rearguard maneuver, but a strategic one, and even if his Entrekinian antics are a bit self- consciously performative, they’re still appreciated by an industry that misses the raffish charm of men like Roger Straus. My uncle Bob, on the other hand, is a corporate guy looking to adapt a system to function within a bottom-line framework. But each seems glad to see the other doing his thing, and Bob leaves the meeting in high spirits.