Emma Bielecki writes on photography as memory made permanent and Alzheimer’s:

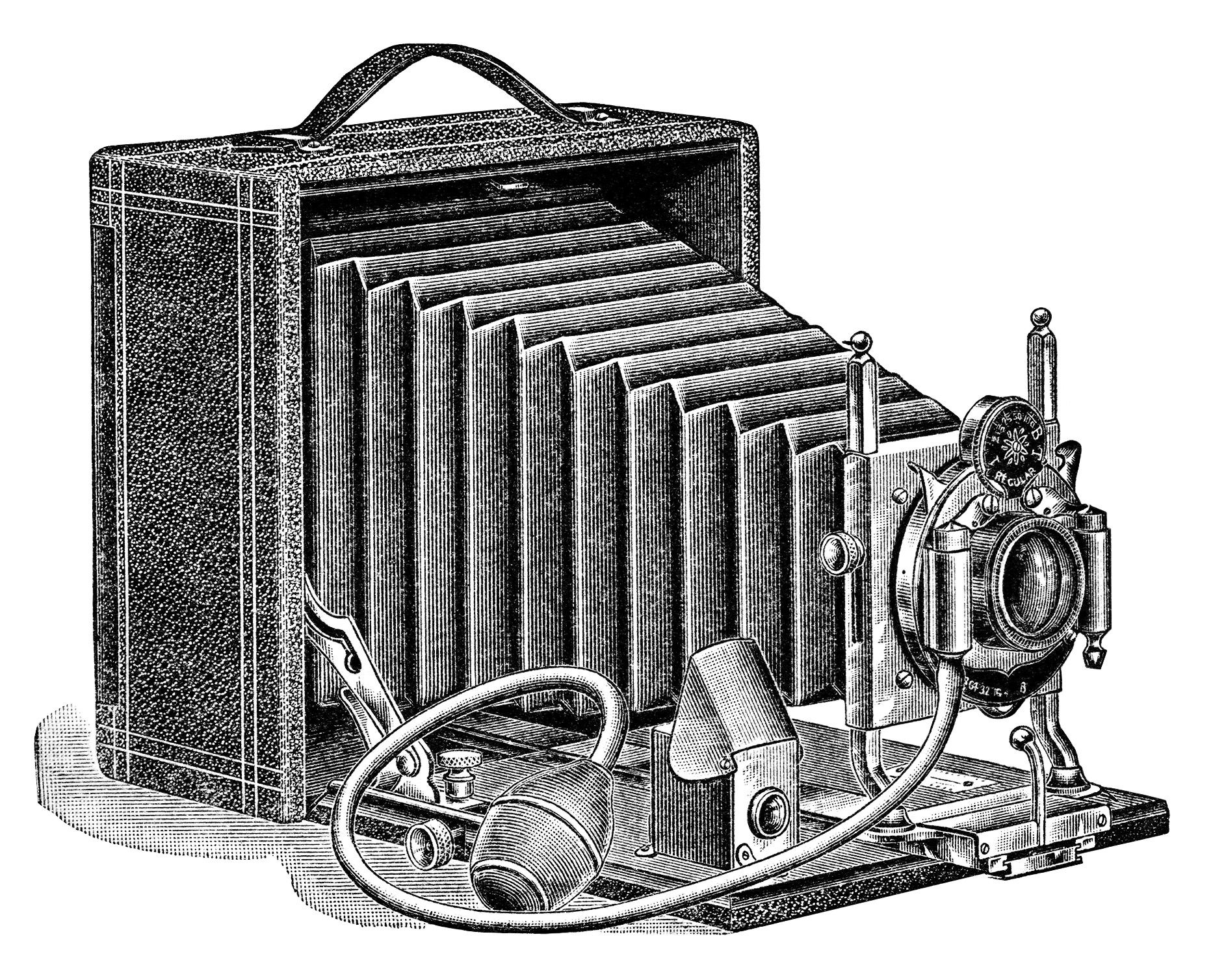

A pinhole camera is a simple device: light passes through an aperture into a box, and an inverted image of the outside is projected on to the opposite wall. Build-your-own kits are sold as novelties, although they are not that novel (indeed, their charm is precisely their quaintness; they vibe old-school, authentic, real). The history of the pinhole camera, written in the margins of the histories of art, science and epistemology, stretches all the way back to the fifth century BC, when the Chinese philosopher Mi To first described one. He called it a ‘locked treasure room’. Locked, presumably, not just because it is an enclosed space, but because the images it generates – fugitive, flickering, ephemeral – are so tantalisingly ungraspable.

It was Nicéphore Niépce, in post-Revolutionary France, who first unlocked the treasure room when he invented a process for fixing the images produced by a camera obscura, capturing them on a glass plate coated with Bitumen of Judea. He called it heliography. His sometime collaborator, sometime rival, Louis Daguerre, who continued refining the process after Niépce’s sudden death from a brain haemorrhage in 1833, preferred the word photography, which was already being used in English to refer to the parallel research being conducted by Henry Fox Talbot. Sun-writing, light-writing – both terms elegantly gloss the means by which a photographic image is produced: light rays bounce off an object in the world and on to a photosensitive surface, passing through an aperture to focus them. ‘Photography you are the shadow / Of the sun / Which is its beauty’, wrote Apollinaire. The (analogue) photographic image is a trace; it is, therefore, indexical, physically linked to the thing it depicts. In that respect, of course, it is quite unlike writing – at least the kind of writing you’re reading here, alphabetic writing: a word after all is merely a set of squiggles and scratches with a purely conventional connection to the thing it signifies. But like writing, photography is a means of making the impermanent permanent, and the absent present.

On my wall hangs a photograph of Bob Dylan in 1965. He’s at a press conference, sitting behind a table. (The oversized lightbulb on the table makes the scene immediately recognizable to even the casual Dylanologist; it features in the opening scenes of Don’t Look Back.) Sitting across the table is a journalist, and behind her a row of photographers. But the photographer who took this particular shot was standing behind the table, behind Dylan. He’s said something to capture his attention, because Dylan has twisted round in his seat to face him. His cigarette is between his lips and his eyebrows are raised, with a slightly quizzical air. Every time I look at the photograph there is a moment where the 50 years between then and now collapse. It’s partly because of the cans: slung round Dylan’s neck they give him a curiously contemporary look. (If the history of the headphone through much of the 20th century describes the pursuit of inconspicuousness, culminating in the invention of the earbud, fashion historians of the future will surely point to unnecessarily oversized circumaural headphones as one of the distinguishing features of early 21st-century style, doubtless identifying it as part of the same nostalgic craving for the paraphernalia of analogue culture that has resurrected the pinhole camera.) But it’s not just because of the cans. It’s the peculiar gift of photography to bring past and present, here and there, into immediate contact. The photographer, manipulating lights and mirrors, a master of optics, is a kind of magician who specialises in one trick, generating the illusion of presence.

The photographer in question was my father, who had worked on Fleet Street before founding his own photographic agency. As a child I wasn’t allowed in his darkroom, but I often imagine him there – happily absorbed in his task, pulling the photo from the stop bath and dunking it in the fixer, surrounded by bottles of developer, stabiliser and toner. ‘Fixer’, ‘stabiliser’, ‘stop bath’ – the language of the darkroom hints at the Sisyphean metaphysical struggle played out there: the struggle to arrest the flux of time. Photography is the art of stabilisation. If my father became a photographer for any reason other than the possibility of earning a good living, I think it was precisely because the photographer is an agent of stability, and his childhood in Central Europe had been characterized by a perilous instability.

(…)