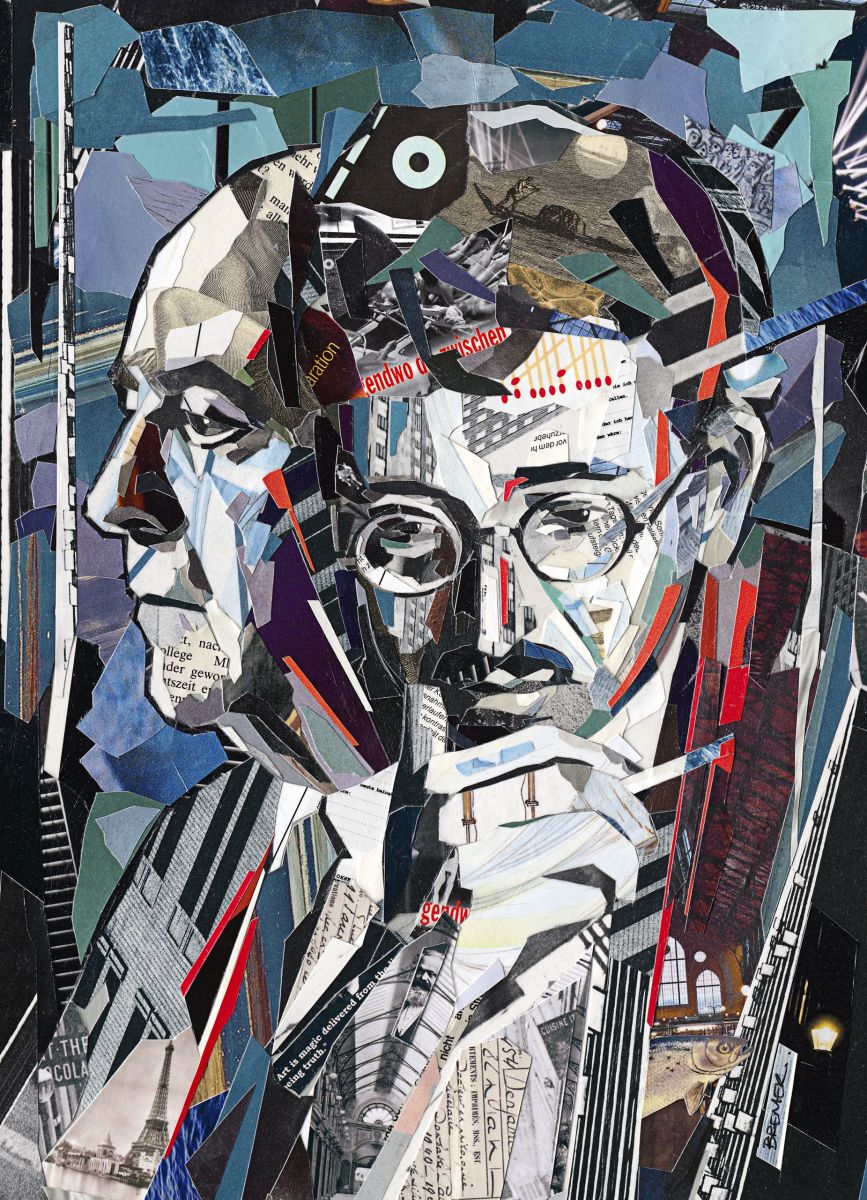

Louise Glück writes for Lit Hub on different interpretations of realism:

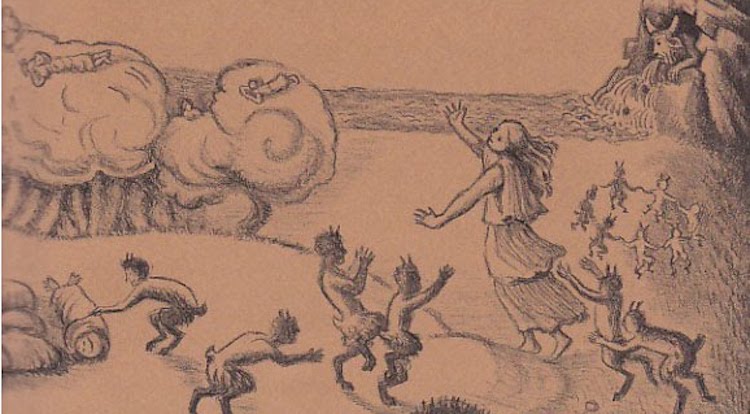

It is entirely possible that I have never had an accurate sense of what is called realism in that I do not, as a reader, discriminate between it and fantasy.

My earliest reading was Greek mythology. As with my prayers, nothing was ever deleted, but categories were added. First the Oz books. Then biography, the how-to books of my childhood. How to be Madame Curie. How to be Lou Gehrig. How to be Lady Jane Grey. And then, gradually, the great prose novels in English. And so on. All these made a kind of reading different from the reading of poetry, less call to orders, more vacation.

What strikes me now is that these quite disparate works, Middlemarch and The Magical Monarch of Mo, seemed to me about equal in their unreality.

Realism is by nature historical, confined to a period. The characters dress in certain ways, they eat certain things, society thwarts them in specific ways; therefore the real (or the theoretically real) acquires in time what the fantastic has always had, an air of vast improbability. There is this variation: the overtly fantastic represents, in imagination, that which has not yet happened (this is true even when it locates itself in a mythic past, a past beyond the reach of documented history). Realistic fiction corresponds roughly to the familiar and present reality of the reader; its strangeness is the strangeness of obsolescence or irrecoverability. Regarding this obsolescence one is sometimes grateful, sometimes mournful. Though the characters in their passions and dilemmas resemble us, the world in which these passions are enacted is vanished and strange. In the degree to which we cannot inhabit that world, the formerly real becomes very like the deliberately unreal.

(…)