One of three new poems by Holly Pester, selected by Sophie Robinson for The Believer:

some women cup their breasts and women without breasts chirp at the thought

women hold their babies up to the light and the women without babies weep at the thought

women with tears in their eyes with gas in their mouth can pose with tigers in the bath

tigerless women check the number of breasts their childless heads their breastless chests

their sore bone rectangular, triangular

armless kids climbed inside a clock

the women with no breasts with red gruesome hair are kin

prepare bowls of hot gum

in our bellies

we have clowns and bugs

we have mock breasts and bellies like bowls of hot gum

frig the dried blue men

a soup for my sister a new earhole where her wound is a light

the women without babies sing into cat bellies

we hunt for sliced up income

for mamma’s dark red underwear

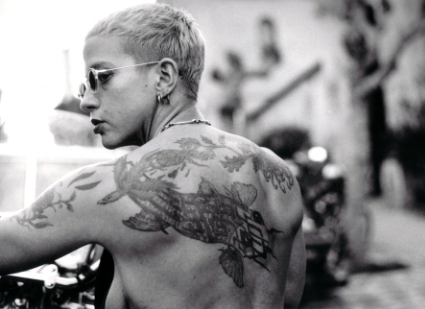

strong girls breathing in rivers

drinking out of each other speaking out of each other’s backs

sing for our empty friend

some river bellies some ocean some singular bump

health custard

bomb shoes

who killed our cave? who let out our weal?

a cave for my baby

a rubber ball full of honey

without babies we chirp into caves into everybody’s cave

drinking a pool of tomato pips and the last strings of egg

delicious forever

find a cave for my injured friend