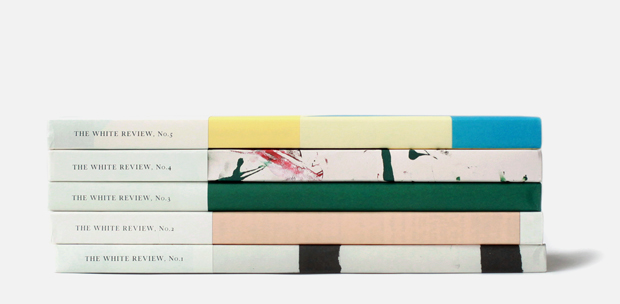

Jacqueline Feldman’s essay on surveillance, paranoia and the emergency state in Paris, featured in The White Review.

(…)

‘Our police are behaving more like American police now,’ I heard last February, at a dinner party in the Sixth Arrondissement. As for the United States, no one’s prognosis was optimistic, but finally the other guests agreed that the Americans had been impressive lately in their protests. They looked at me. Bravo, they said. Certainly, they added, aspects of the Women’s March had been problematic, but overall they had been cheered to read of the assemblies. One only hoped the French, too, would turn out so numerously were Marine Le Pen elected President, as the guests expected she would be.

I noticed the poster which read Respond to a terrorist attack in a doctor’s office, and subsequently, I would see it in libraries. It looks like an in-flight safety guide, but these stick figures flee, push a couch against a door, silence their phones and crouch behind a pillar. Also new since I moved away were the guards who searched purses at the doors to grocery stores. While the 1955 law creating an emergency state authorised house arrest for ‘anyone… whose activity proves dangerous to security and public order,’ the 2015 revision specifies that it may be applied to those for whom exist ‘serious reasons to think their behaviour constitutes a threat to security and public order,’ and, in this way, deemphasises their behaviour in favour of what is thought about them. The law that replaced the emergency state on 1 November 2017 requires a judge’s sign off before searches, though not ‘individual measures of administrative control and surveillance’, the former house arrests, but it preserves this wording. Another criterion must, now, co-present: the list of possibilities includes apologia for terrorism. Defined by the November 2015 law, the house arrests – numbering 400 in the law’s first three months, though at last count on 30 October, only 41 were in effect – might have required suspects to stay someplace other than their home, to stay in place for as many as twelve hours, to check in with authorities as many as three times daily, to wear an ankle bracelet, to turn in a passport or to break off a relationship deemed suspicious. The new law diminishes these impositions, for example by widening the bounds of the detainment to an entire town, and by limiting the frequency with which suspects must check in to once daily. Sensibly, both 1955 and 2015 laws stipulate these house arrests should not ‘take the effect of creating camps’. These laws have been compared with the US PATRIOT Act, passed in October 2001; another American analogue for its near-unanimous passage days after the 9/11 Attack, the Authorisation of Use of Military Force, provides for strikes abroad against the perpetrators as well as anyone understood to be ‘associated forces’. The French emergency state, by contrast, addressed an enemy within. It was developed as temporary, requiring a vote after twelve days, but remained in effect continuously after November 2015, involving six renewals of varying lengths. While politicians including the president touted the new law as a way out of this widely ironised predicament of permanent emergency, they simultaneously insisted the law pass before the emergency state expired, so that protection would be continuous. ‘I’ve decided that in November we will emerge from the rule of law,’ Macron said on 19 September in New York. He corrected himself, having meant to say not état de droit but état d’urgence, emergency state.

More generally visible is the governmental threat metric Vigipirate, with its signs hanging in public buildings, and operations of the police or military, such as Sentinelle, which has stationed soldiers throughout the country since the shooting at CHARLIE HEBDO in January 2015. Sentinelle has elicited censure for its expense as well as the question, after a man drove a car into six of these soldiers in the Parisian suburb Levallois-Perret on 9 August, wounding them, as to whether it creates targets. Also controversial has been the surveillance law developed in 2015, which allows the government to monitor phone and Internet usage automatically. Last January, I stayed with environmentalists who, before meetings, collected phones from those present, placed them in a receptacle, set it down outside the room, and closed the door. I hear that lately, they have used a microwave, figuring that it blocks signals completely. The converted barn where they live in Bure, Meuse is a 21-kilometre drive over fields from the nearest market town. They recalled a period of relentless vehicular searches the previous summer. Then as now police were behaving as ‘cowboys’, they told me, using that English word. One of these activists explained that, after breaking the windshield of a car belonging to police who were, by his account, taunting him, he was considered wanted, and that when he was picked up, protesting a revision to French labour law in Nancy, the physical brutality of his apprehension struck him as disproportionate. He could not be sure of this, but it would come to seem of a piece with the other activists’ experiences. He had required new glasses. His treatment may not have been explicitly permitted by the legislation, but, as another of the activists wrote to me, mimicking gendarmes’ remarks, ‘It’s the emergency state, we do what we want.’ This group of activists has made headlines for a foot injury sustained by one of them while protesting, the effect of a gendarme’s stun grenade, as well as a raid on 20 September resulting in the seizure of some forty computers.

A sense of futility had accompanied me following my move back to the US, as if I had, by leaving, given up on Paris. During the attacks in November 2015, I was concentrating in an apartment where I had moved a few weeks previously, drafting an article about the accents of American presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump, who are from New York City, where I found I now lived. Such commentary had to be formulated from the posture of an observer. I had adopted it cynically. Only when we’re lucky enough to live comfortably do we regard the geopolitical landscape as if through a window. Sometimes, it breaks. Citing N. H. Julius, the nineteenth-century German physician and writer on prisons, Foucault locates Jeremy Bentham’s famous panopticon historically, at the advent of the modern state, with which individuals found themselves engaged in a preeminent relationship. Discipline had been achieved by spectacle, a theatre of the scaffold; now, those who had been onlookers were monitored themselves. While the act of watching characterises the panopticon in the popular imagination, essential too to the machinery is the isolation of the watched, their ‘lateral invisibility’, and their inability to verify the watching. Venetian blinds as well as dividing walls conceal any guard in the watchtower, even the guard’s shadow. In the unfamiliar city I fielded messages from distant friends, who thought that I still lived in Paris. Waiting to hear from Parisian friends, I checked Twitter and, scrolling, wondered whether it was required of me to post.

(…)