Notorious Cuban revolutionary and long-term leader Fidel Castro died on Friday at age 90 after a long illness, leaving a complicated legacy—some heralding him as a liberating hero and others decrying him as a ruthless dictator. Whatever else he may have been, it seems that Castro was an avid reader—“ours is an intellectual friendship,” Gabriel García Márquez once said—and he has been tied to a number of literary figures over the years, with varying degrees of importance, not to mention veracity. Below, a brief history of Castro’s relationships, whether good, bad, or not actually very real, with some of the most famous writers of our time.

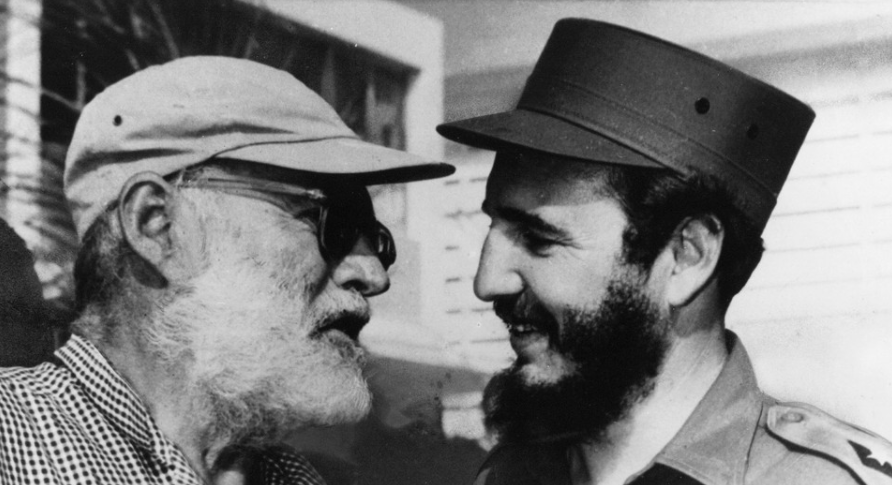

Fidel Castro + Ernest Hemingway

It’s a widely known fact that Fidel Castro and Ernest Hemingway were friends. Just look at all those cozy pictures of them, right? Well, the truth is that all of those cozy pictures were taken on the same day, because that was the only day they met—and they didn’t even say much to each other.

As Jacobo Timerman explained in The New Yorker: “The revolutionaries never viewed Hemingway sympathetically; he had taken little interest in Cuba… Although it’s never stated explicitly, the tourist gets the impression that Hemingway supported Fidel Castro, that the writer is part of the Revolution. The truth is that… the regime never managed to establish a solid link between Hemingway and Castroism.”

And all those pictures? They all come from one day in May of 1960, when a fishing contest was held in Hemingway’s honor. “There are numerous photographs of that meeting,” Timerman writes, “but nothing noteworthy in the words that were exchanged before witnesses—mere formalities, really.” In fact, Hemingway was probably mostly trying to get Castro to keep from confiscating his land.

So when you visit, remember: all that Hemingway + Castro stuff is just tourist bait (read: money). That shouldn’t keep you from enjoying your mojitos, though.

Fidel Castro + Pablo Neruda

This is a case of a friendship that could have been—should have been, even—but, well, wasn’t. Pablo Neruda, himself a communist (he was even, briefly, a Senator for the Chilean Communist Party) was a major admirer of Fidel Castro—and an ardent lover of Cuba in general. In 1959, he visited the country and met the newly powerful Castro in Caracas. As he writes in his memoirs:

Fidel spoke for four uninterrupted hours in the huge square of El Silencio, the heart of Caracas. I was one of the 200,000 people who stood listening to that long speech without uttering a word. For me, and for many others, Fidel’s speeches have been a revelation. Hearing him address the crowd, I realized that a new age had begun for Latin America. I liked the freshness of his language. Even the best of the workers’ leaders and politicians usually harp on the same formulas, whose content may be valid, though the words have been worn thin and weakened by repetition. Fidel ignored such formulas. His language was didactic but natural. He himself appeared to be learning as he spoke and taught.

Later, Neruda describes a secret meeting he had with Castro:

He was a head taller than I. He came toward me with quick strides.

“Hello, Pablo!” he said and smothered me in a bear hug.

His reedy, almost childish voice, took me by surprise. Something about his appearance also matched the tone of his voice.

Fidel did not give the impression of being a big man, but an overgrown boy whose legs had suddenly shot up before he had lost his kid’s face and his scanty adolescent’s beard.

Brusquely, he interrupted the embrace, and galvanized into action, made a half turn and headed resolutely toward a corner of the room. I had not noticed a news photographer who had sneaked in and was aiming his camera at us from the corner. Fidel was on him with a single rush. I saw him grab the man by the throat and start shaking him. The camera fell to the floor. I went over to Fidel and gripped his arm, frightened by the sight of the tiny photographer struggling vainly. But Fidel shoved him toward the door, making him disappear. Then he turned back to me, smiling, picked the camera off the floor, and flung it on the bed.

In 1960, Neruda published Canción de gesta, a collection that included the poem “ A Fidel Castro,” which to my eyes at least appears to be a strong-voiced message of support for the leader.

But in 1966, after Neruda visited the United States (and the anti-Castro Peru), Cuba turned its back on him. In July, a group of Cuban intellectuals—on orders, it was said, from Castro himself—published a scathing public letter condemning Neruda for betraying their Communist principles by associating with the enemy. According to biographer Adam Feinstein, Neruda felt that the letter had been written because “Castro had not taken kindly to his only half-veiled warning [in his poem “A Fidel Castro”] to the Cuban leader to avoid making a cult of his public persona.” Neruda, insulted, angry, and feeling that Castro hated him personally, never went back to Cuba, though he was invited only two years later.

(…)