On February 29, 1988, John Ashbery gave a poetry reading at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC. The room was packed. Coincidentally, the Folger had mounted “Marianne Moore: Vision Into Verse,” an exhibition including an array of clippings and photographs that Moore includes in her poems—most prominently in “An Octopus,” the longest poem in her 1924 volume Observations. Speaking from the podium, Ashbery called “An Octopus” the most important poem of the 20th century; and while the remark provoked a few titters, he was reiterating a conviction that was neither novel nor idiosyncratic. “Despite the obvious grandeur of her chief competitors,” he’d written two decades earlier, in a 1967 review of Moore’s Complete Poems, “I am tempted simply to call her our greatest modern poet.”

By “chief competitors,” Ashbery meant the usual suspects—Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, Robert Frost, William Carlos Williams—all of whom maintain a permanent claim on our attentions; with the notion that Moore belongs among this company, no 21st-century reader could plausibly disagree. Not only the freewheeling Ashbery but also the fastidious Richard Wilbur reveres her poems, and depending on how one approaches them, the poems themselves seem both freewheeling and fastidious. “She gives us,” said Ashbery, “the feeling that life is softly exploding around us, within easy reach.”

In a sense, this is true of any great poem, which will seem seductively unpredictable, a thrilling journey from first line to last, to the degree to which it is exquisitely constructed. No poet is more formally precise than Walt Whitman at his most expansive, no poet more wildly extravagant than Emily Dickinson at her most curtailed; freedom is not sloppiness, structure is not constriction. But perhaps more clearly than any poet of the 20th century, Moore allows us to see why this is the case. Hence her extraordinary usefulness for other poets, hence her lasting influence even on poets who do not sound like her, much less transform her discoveries into mannerisms.

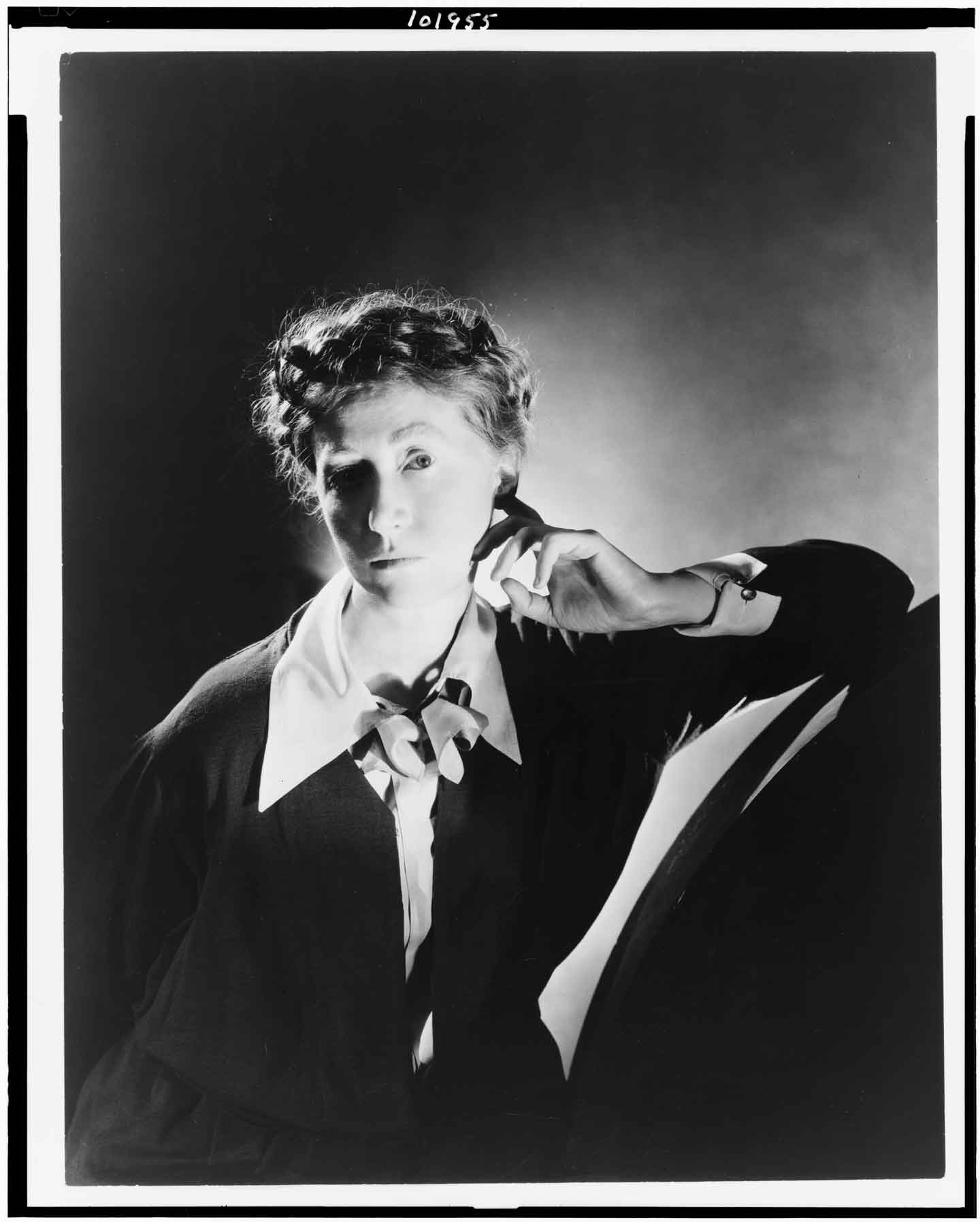

Moore was born near St. Louis, Missouri, in 1887. Her parents separated before her birth, and subsequently her father, already institutionalized, severed his hand, taking literally the injunction of Matthew 5:30 (“If thy right hand offend thee, cut it off”). To her mother and her brother Warner, who became a Presbyterian minister, Moore remained fiercely, sometimes pathologically close. Though she attended Bryn Mawr College, became a suffragette, moved to a tiny Greenwich Village apartment in 1918, and edited the legendary magazine The Dial from 1925 until its demise in 1929 (an achievement that would ensure our interest in Moore even if she had written no poems), she lived with her mother until her mother’s death in 1947. It’s hard to imagine Marianne Moore sharing a bed with her mother while also composing her fiercely syntax-driven poems—poems in which domestic relations often seem pointedly nightmarish: “the spiked hand / that has affection for one / and proves it to the bone, / impatient to assure you / that impatience is the mark of independence / not of bondage.”

Moore began publishing these poems around 1915, and immediately they were noticed by the poets who became her peers—Pound, Eliot, Stevens, H.D., Williams—poets who would each write admiring essays about her work. Yet Moore remained mysterious. “Does your stuff ‘appear’ in America?” asked Pound after first encountering her poems in England. “Dear Mr. Pound,” replied Moore, “I do not appear.” In 1921, H.D. helped to arrange the appearance of a small collection, called Poems, but Moore was neither involved with the publication nor pleased with the results. She held out as long as she could, finally publishing her first book, Observations, with the Dial Press in 1924; a slightly revised second edition appeared the following year. Though Moore would continue to write superb poems throughout her long life (she died in 1972), she would never surpass the achievement of Observations, which is not merely a collection of discrete poems but a poetic omniverse of Whitmanian proportions.

Moore was a passionate reviser. Prior to being collected in Observations, her poems appeared in little magazines in sometimes drastically different versions, and she continued to revise them for decades to come. Reading a poem from the 1920s in her 1967 Complete Poems, often one is in fact reading a poem from 1935 or 1951; this conundrum was wildly exacerbated by the recent Poems, which reprints (in the words of the volume’s editor, Moore’s friend Grace Schulman) “versions [of the poems] that I liked.” In addition, because Moore’s various selected and collected editions rearrange and omit some of the poems of Observations, the design of this volume has largely been obscured. A facsimile edition appeared in 2002 (Becoming Marianne Moore: The Early Poems, 1907–1924, meticulously edited by Robin Schulze), but it is only now that Moore’sObservations has finally been reprinted as a book that devoted readers might hold in their hands.

[…]

‘Less is Moore’

James Longenbach on Marriane Moore for The Nation