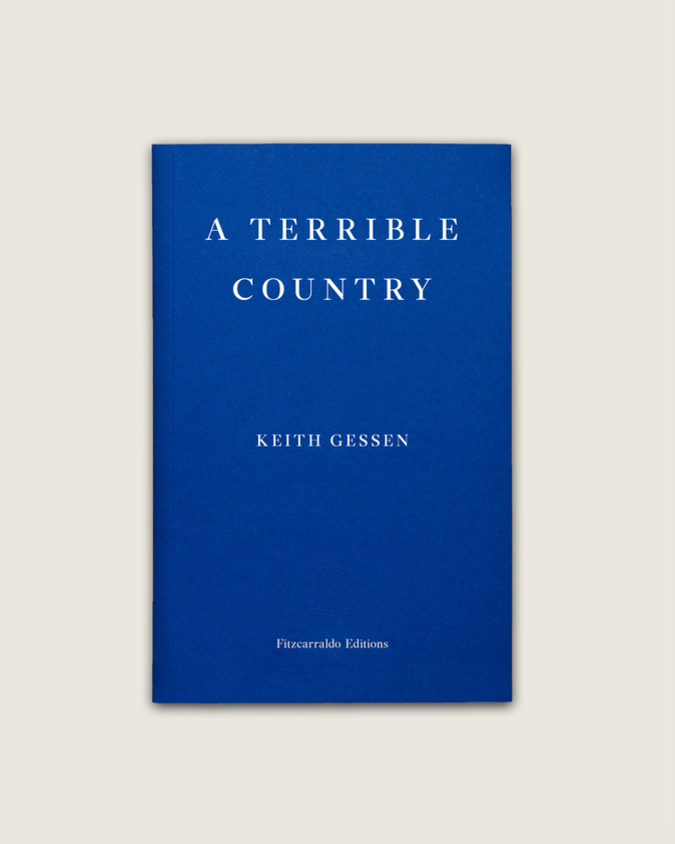

An excerpt from Keith Gessen’s novel A Terrible Country, published today:

I. I MOVE TO MOSCOW

In the late summer of 2008, I moved to Moscow to take care of my grandmother. She was about to turn ninety and I hadn’t seen her for nearly a decade. My brother Dima and I were her only family; her lone daughter, our mother, had died years earlier. Baba Seva lived alone now in her old Moscow apartment. When I called to tell her I was coming, she sounded very happy to hear it, and also a little confused.

My parents and my brother and I left the Soviet Union in 1981. I was six and Dima was sixteen, and that made all the difference. I became an American, whereas Dima remained essentially Russian. As soon as the Soviet Union collapsed, he returned to Moscow to make his fortune. Since then he had made and lost several fortunes; where things stood now I wasn’t sure. But one day he Gchatted me to ask if I could come to Moscow and stay with Baba Seva while he went to London for an unspecified period of time.

“Why do you need to go to London?”

“I’ll explain when I see you.”

“You want me to drop everything and travel halfway across the world and you can’t even tell me why?”

There was something petulant that came out of me when dealing with my older brother. I hated it, and couldn’t help myself.

Dima said, “If you don’t want to come, say so. But I’m not discussing this on Gchat.”

“You know,” I said, “there’s a way to take it off the record. No one will be able to see it.”

“Don’t be an idiot.”

He meant to say that he was involved with some very serious people, who would not so easily be deterred from reading his Gchats. Maybe that was true, maybe it wasn’t. With Dima the line between those concepts was always shifting.

As for me, I wasn’t really an idiot. But neither was I not an idiot. I had spent four long years of college and then eight much longer years of grad school studying Russian literature and history, drinking beer, and winning the Grad Student Cup hockey tournament (five times!); then I had gone out onto the job market for three straight years, with zero results. By the time Dima wrote me I had exhausted all the available post-graduate fellowships and had signed up to teach online sections in the university’s new PMOOC initiative, short for “paid massive online open course,” although the “paid” part mostly referred to the students, who really did need to pay, and less to the instructors, who were paid very little. It was definitely not enough to continue living, even very frugally, in New York. In short, on the question of whether I was an idiot, there was evidence on both sides.

Dima writing me when he did was, on the one hand, providential. On the other hand, Dima had a way of getting people involved in undertakings that were not in their best interests. He had once convinced his now former best friend Tom to move to Moscow to open a bakery. Unfortunately, Tom opened his bakery too close to another bakery, and was lucky to leave Moscow with just a dislocated shoulder. Anyway, I proceeded cautiously. I said, “Can I stay at your place?” Back in 1999, after the Russian economic collapse, Dima bought the apartment directly across the landing from my grandmother’s, so helping her out from there would be easy.

“I’m subletting it,” said Dima. “But you can stay in our bedroom in Grandma’s place. It’s pretty clean.”

“I’m thirty-three years old,” I said, meaning too old to live with my grandmother.

“You want to rent your own place, be my guest. But it’ll have to be pretty close to Grandma’s.”

Our grandmother lived in the center of Moscow. The rents there were almost as high as Manhattan’s. On my PMOOC salary I would be able to rent approximately an armchair.

“Can I use your car?”

“I sold it.”

“Dude. How long are you leaving for?”

“I don’t know,” said Dima. “And I already left.”

“Oh,” I said. He was already in London. He must have left in a hurry.

But I in turn was desperate to leave New York. The last of my old classmates from the Slavic department had recently left for a new job, in California, and my girlfriend of six months, Sarah, had recently dumped me at a Starbucks. “I just don’t see where this is going,” she had said, meaning I suppose our relationship, but suggesting in fact my entire life. And she was right: even the thing that I had once most enjoyed doing—reading and writing about and teaching Russian literature and history—was no longer any fun. I was heading into a future of halfheartedly grading the half-written papers of half-interested students, with no end in sight.

Whereas Moscow was a special place for me. It was the city where my parents had grown up, where they had met; it was the city where I was born. It was a big, ugly, dangerous city, but also the cradle of Russian civilization. Even when Peter the Great abandoned it for St. Petersburg in 1713, even when Napoleon sacked it in 1812, Moscow remained, as Alexander Herzen put it, the capital of the Russian people. “They recognized their ties of blood to Moscow by the pain they felt at losing it.” Yes. And I hadn’t been there in years. Over the course of a few grad-school summers I’d grown tired of its poverty and hopelessness. The aggressive drunks on the subway; the thugs in tracksuits and leather jackets walking around eyeing everyone; the guy eating from the dumpster next to my grandmother’s place every night during the summer I spent there in 2000, periodically yelling “Fuckers! Bloodsuckers!” then going back to eating. I hadn’t been back since.

Still, I kept my hands off the keyboard. I needed some kind of concession from Dima, if only for my pride.

I said, “Is there someplace for me to play hockey?” As my academic career had declined, my hockey playing had ramped up. Even during the summer, I was on the ice three days a week.

“Are you kidding?” said Dima. “Moscow is a hockey mecca. They’re building new rinks all the time. I’ll get you into a game as soon as you get here.”

I took that in.

“Oh, and the wireless signal from my place reaches across the landing,” Dima said. “Free wi‑fi.”

“OK!” I wrote.

“OK?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Why not.”

(…)