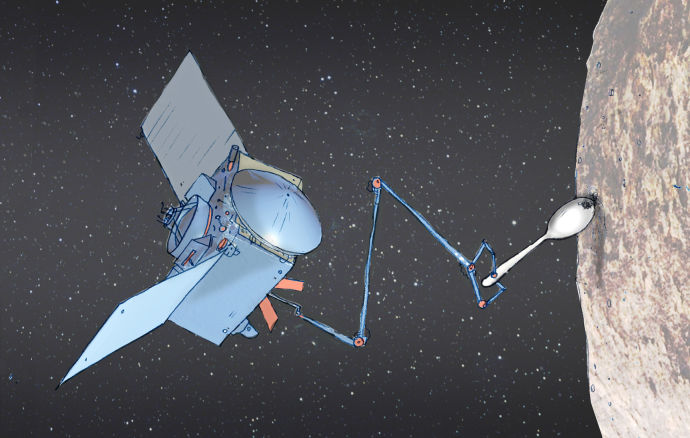

Elizabeth Colbert on NASA’s latest OSIRIS-REx mission, for the New Yorker:

The ancient Egyptians believed that the universe emerged from an ocean called Nun, boundless and inert. At the beginning of time, a mound pierced the surface of the waters and rose from the void. Upon the mound stood the sun god Atum, who summoned the cosmos into being. Slowly, nothing became everything. Atum had two children, who had two children of their own: Geb, the earth, and Nut, the sky. They fell in love, as divine siblings often do, and conceived two sons and two daughters. The firstborn, Osiris, was the rightful ruler of Egypt, but his younger brother, Set, was consumed with jealousy. He murdered Osiris and dismembered his corpse, scattering it in pieces across the kingdom. The remains fertilized the Nile and made the desert bloom.

The story of our solar system, as astrophysicists know it, is not so different. It begins with another vast expanse of inert stuff—a cloud of gas and dust. Some 4.6 billion years ago, the cloud stirred, perhaps troubled by a passing star or the shock waves of a nearby supernova, spreading out into an immense disk that began to spin. At the center of the disk was a white-hot mass of plasma, which devoured most of the material around it and became our sun. Its energy and gravity sorted the rest of the disk by kind. The hardy substances, like rocks and metals, remained close to the center, where they coalesced into the inner planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. The more fragile compounds retreated to the far reaches of the disk, beyond what astronomers call the snow line, forming the gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune) and the frigid remainders beyond (Pluto, the comets, and the embryos of planets that never materialized). The story ends, of course, with life. It’s what happened in the middle—what made the desert bloom—that still has scientists flummoxed.

For a cell to survive, it requires three ingredients: nucleic acids, like DNA and RNA, to guide its development; amino acids to build proteins; and a lipid envelope to protect it from the elements. When life on our planet got its start, nearly four billion years ago, Earth was short on these ingredients. Where did they come from? The prevailing theory centers on a period known as the Late Heavy Bombardment. It suggests that, at the time, the solar system had not reached its current equipoise; the giant planets were on the move, and their gravity jostled free large numbers of asteroids and comets. Some drifted away into interstellar space, but others rushed inward, battering Earth with rock and ice. The onslaught lasted many millions of years, and though it brought unimaginable ruin it may also have seeded our planet with the chemical precursors of life. Very little now remains of that primordial Earth, but over the years meteorites have provided tantalizing clues of what might have fallen here, Osiris-like, from above. The Murchison meteorite, for instance, which struck rural Australia, in 1969, has been found to contain more than a hundred varieties of amino acid, along with the building blocks of lipids.

(…)