I have very few childhood memories of my paternal grandmother, Barbara Hughes (née Holland). I really got to know her in my twenties. By that time, neither of us bothered with conventional grandmother-granddaughter roles. We became friends and have shared hundreds of correspondence, mostly online.

In an early email to her in 2008, I asked Barb about her husband, my paternal grandfather, who I could barely remember. Architect, playwright, drinker, rogue. The ‘playwright’ part was beginning to interest me, a gradually engaging student of literature. I wanted to know more. She put the answer on hold, replying only that: ‘I am dogged by the feeling that I must get the record of his tremendous talent documented’.

In eleven of Barb’s emails to me she refers to herself as a ‘BOVLB’ (AA Milne’s ‘bear of very little brain’). In a 2012 email, long after I’d begun to suspect who the creative energy in that duo had really belonged to, she confirmed my inkling that she was in fact a bear of very considerable brain (and wit, creativity and talent) who had simply not been seen in the same light as her husband: ‘My favourite situation has always been a reflected glory glow!’ she signed off, cheerfully, as if she had not just encapsulated the sad fate of all wives to husbands who encourage (or don’t discourage) an idea of themselves as ‘tremendous talents’.

Today, her artistic legacy outshines his: dozens of poems, paintings and sketches, years’ worth of diaries that chronicle an extraordinary self-education in classical music (a concert a night, for a time); an incognito creative life that I might have known nothing about had she not insisted, throughout her turbulent life, on writing for herself. Her husband published. She wrote.

This week, the suddenly Barbaraless, locked-down world beyond my house is unrecognisable and inaccessible, and I have time to sit with her emails, song recommendations and poems (or the ‘best ones […] and that’s not saying much’), which she emailed me over the years, remembering not the grandmother, but the woman who never stopped writing.

The diarist

Here is an entry from Saturday 30th March 1946, when she visited Leonard Woolf (something about a broken gramophone). A pioneer of the ‘accompanying playlist’, in her diaries there is a song for every occasion:

‘A foggy day in London town (sung by Frank Sinatra or Ella Fitzgerald). The bus crept along and I was late getting to Victoria. He was standing in the street, his back towards me, looking up at the Mansion flats as if he had not seen them before. Was he expecting her to emerge from the building, the sound of that clanking lift, a muffled echoing reaching outside. Leonard turned around and lifted both arms, bringing the palms of his hands together in an instant prayer. “Virginia hated fog – in London”. His arm around my shoulder we went in…..’

The letter writer

I have three of her paintings hanging by the entrance to my house like amulets.

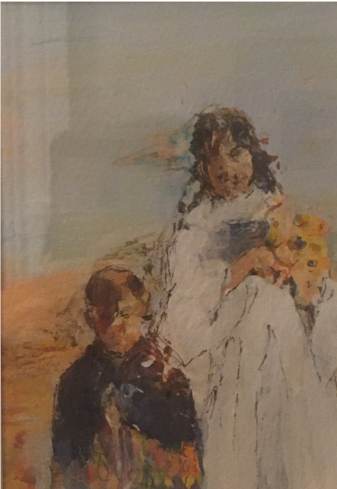

One of them (pictured above) was painted from a photograph taken in early January 1978, from a period in the seventies when Barb was living in Abu Dhabi and later in Al Ain. She was, she told me in an email from 2012, like the speaker in Walter de la Mare’s poem, ‘crazed with the spell of far Arabia’: ‘These kids were straight out of the desert – those lovely orange flowers from the great garden city of Al Ain just springing up, were theirs.’ Barb had a way of seeing and remembering people. Some of her emails remind me of Natalia Ginzburg’s personal essays in this respect, but also perhaps because of that classic Ginzburgian line, which is also classic Barb: ‘There is one corner of my mind in which I know very well what I am, which is a small, a very small writer.’ Barb was a small writer, but one whose words, unspooling without punctuation from her naturally digressing mind, or springing up like lovely orange flowers between parenthesis, were hers.

The poet

For some time now,

weeks,

I have been half dead:

not under the ground,

resting

in a brown funereal

parlour,

not grim, but rather

jolly:

like a French film coffin

knowing

the funny man would come,

trip,

and lift the lid.

Certainly the top would come off.

I did not expect

a tune

from Claude Debussy

dying of cancer

1914

out of the sepia

listening

a tight white light

firing

each vertebra

once,

life lumber puncture.

Certainly I could stand up again.

Barbara Hughes

15 January 1926 – 19 March 2020

* Claude Debussy, Sonata for Violin and Piano in G Minor, played by Alfred Cortot and Jacques Thibaud. Sophie Hughes is the translator of Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor.