For the Paris Review, Sarah McColl on the life and work of Jo Hopper.

In a 1906 portrait of Josephine Nivison, painted while she was a twenty-two-year-old student at the New York School of Art, her artist’s smock slips from her shoulder like the falling strap of Madame X’s gown. This is teacher Robert Henri’s portrait of the artist as a young woman; one suggestive detail, sure, along with aspects of Jo’s character he can’t help but capture: her steady gaze of steely resolve, the way she holds her brushes like a divining rod.

This is when Jo Nivison meets Edward Hopper, though they do not make much of their first meeting, or even their second. When they graduate, Jo keeps herself in cigarettes by selling drawings to places like the New York Tribune, the Evening Post, the Chicago Herald Examiner. In the 1920 New York City Directory, Jo lists herself as an artist, and she is no slouch. She shows her paintings alongside work by Picasso and Man Ray. In that same directory, Edward Hopper calls himself an illustrator.

Jo and Ed don’t link up their wagons until 1923. It is the third time their paths have crossed, and by now they are both in their forties. Maybe they can help each other. Six of Jo’s watercolors appear that year in a group show at the Brooklyn Museum; she puts in a word for Ed with the curators, and they buy one of his paintings. It is the first he has sold since the Armory Show of 1913, ten years before.

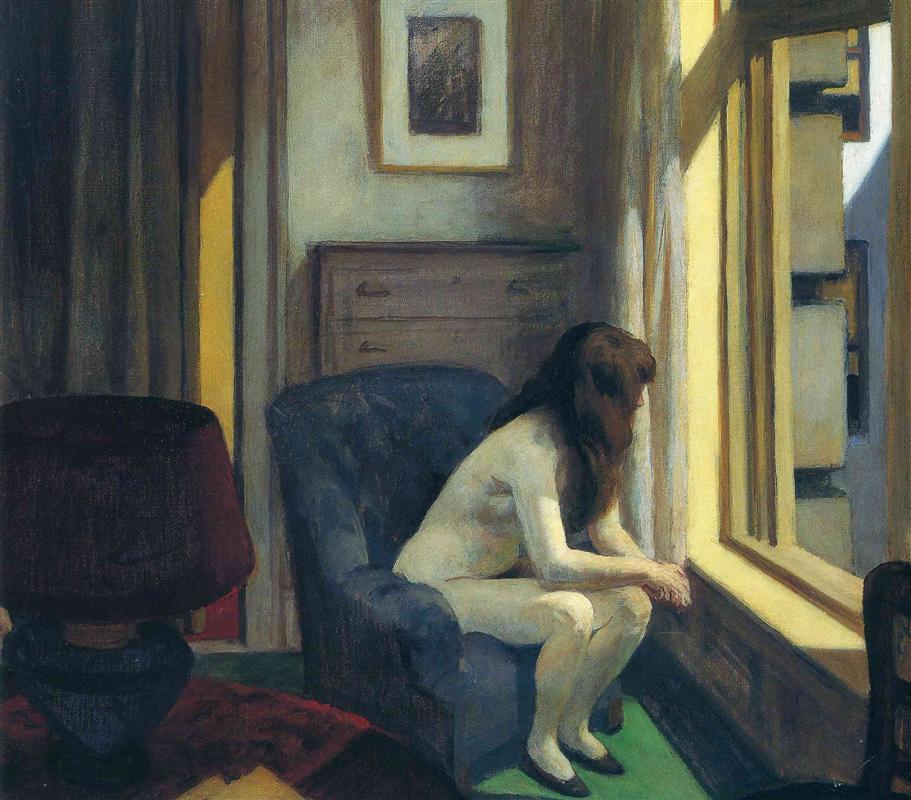

This is Ed’s tipping point. Next, he’s given a sellout solo show by the gallery that represents him for the rest of his life, and Jo becomes Ed’s only model. She creates characters for his work, transforms herself into women alone, idle, waiting. She is woman in a train compartment, woman in the office at night, at a New York movie, a woman in the sun. She is painting, too—she always has—but there are murmurs that Jo is riding Ed’s coattails onto the gallery walls. In 1938, there is a group show at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, and in 1939, another at the Golden Gate International Exhibition. Here, Jo’s oil painting “Chez Hopper” appears, and it is a portrait of Ed for once, in which his feet rest on a coal stove. This painting, as is the case with most of Jo’s work, has been lost.

But that’s rushing ahead to the end of the story. The beginning, and the middle, is that Jo and Ed are always painting and always fighting. They work together in their sometimes home on the Cape and their other-times home, a skylight-bright fourth-floor walk-up on Washington Square. Ed hauls coal and tin cans of beef stew up the stairs. If only his wife would do less painting and more cooking. Nobody likes her work, he says. He means he does not care for it.

Their fights, as Jo records in her diaries, are vicious. Jo scratches Ed and “[bites] him to the bone.” He slaps her, bangs her head against a shelf, colors her with bruises. On their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary, she tells him they deserve a medal for distinguished combat, and he complies with a coat of arms made from a rolling pin and ladle.

It is true: Jo is a lady flower painter, but things are not only as they seem. Sometimes she is thinking of her dead friends, other women. She calls the 1948 painting of a brittle, drooping arrangement set before an open window, “Obituary.” “She intentionally disregarded the dominant male aesthetic,” the Hopper historian Gail Levin writes. “Her subject matter seems self-consciously female.” In her early seventies, Jo paints a self-portrait in which she wears earrings, a necklace, and a pink lace bra, which she purchased for herself as a birthday present from Ed. It was “the most expensive thing of the kind I’ve ever owned,” she wrote in her diary. The lingerie is “perishable & does nothing specially for me anymore than another layer of skin.”

(…)